In late 1942, a Pittsburgh freelance artist named J. Howard Miller painted a poster for Westinghouse Electric, his biggest client. All told, Miller designed 42 posters that would be hung on nearly 2,000 bulletin boards and factory walls across the country as wartime production kicked into high gear. This particular poster, however, was one of his simplest and most powerful compositions: a confident, bandana-coifed “woman war worker” making a muscle. A cartoon balloon above her head contained the message, “We Can Do It!” In the post-war years, this image, now recognized worldwide as “Rosie the Riveter,” has taken on added meaning and importance.

Some historians would have us believe that Miller’s iconic Rosie had little public impact during the war because it was distributed only to Westinghouse plants in an effort to boost morale and stimulate production. In fact, the “We Can Do It!” poster had a ripple effect that redounds to Pittsburgh’s credit to this day. But how did Miller’s portrait of a Westinghouse worker in Pittsburgh become Rosie the Riveter?

The convergence of the image and name was entirely serendipitous. In late 1942, as Miller put the finishing touches on his pretty but powerful “poster girl,” the song-writing duo of Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb came up with a catchy tune that Kay Kyser, Allen Miller, The Four Vagabonds, and others quickly popularized.

Millions of Americans turned up their radios to hear how “Rosie the Riveter” worked all day long, rain or shine, on the assembly line: “She’s making history, working for victory, Rosie [rat-a-tat-tat] the Riveter!” The hit song was released the same week as Miller’s poster in February 1943. Hundreds of thousands of war workers saw the posters just as the Rosie the Riveter radio craze swept the nation.

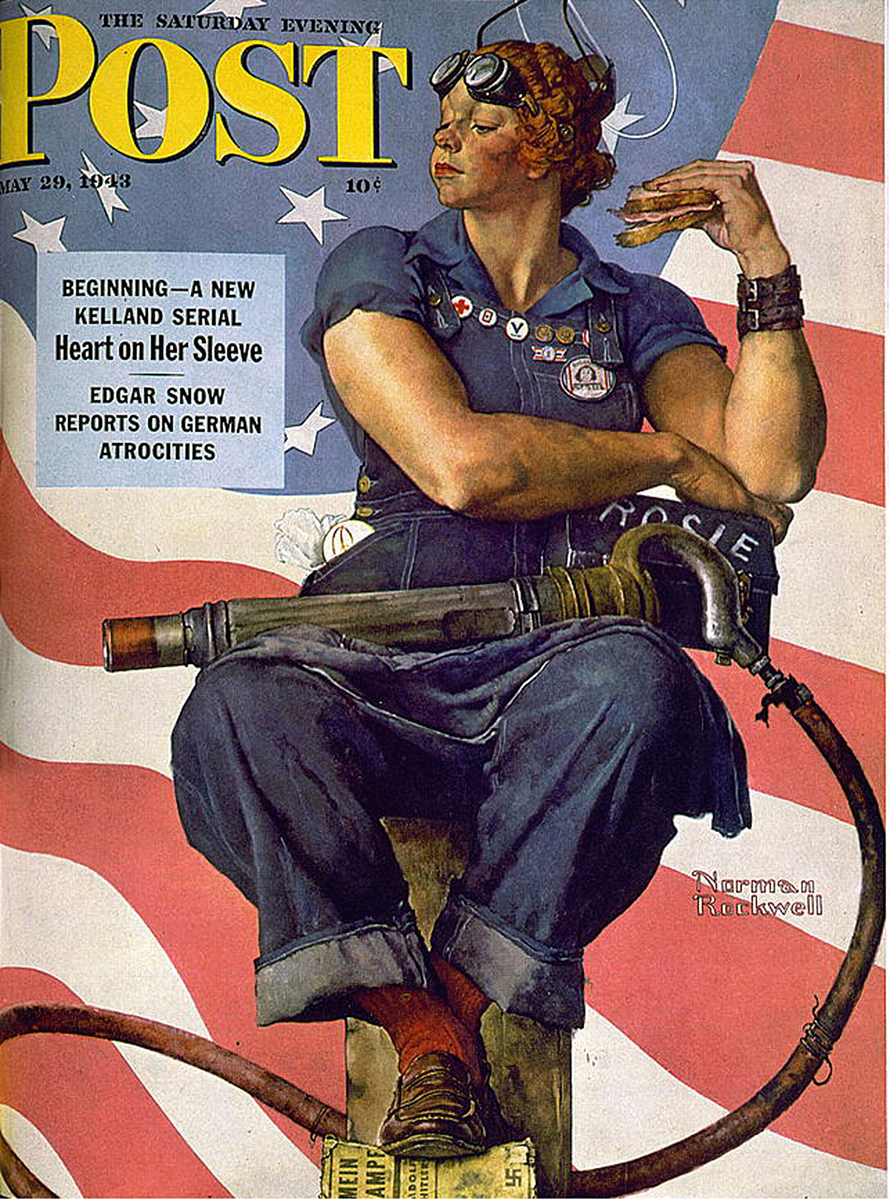

The image was photographed and republished in a variety of publications. Millions of Americans then saw Norman Rockwell’s satirical Rosie image on the May 29, 1943, cover of the Saturday Evening Post. Playing on Miller’s theme, Rockwell’s Rosie makes a muscle while nonchalantly eating a sandwich, her foot perched disrespectfully on a copy of Mein Kampf. Rockwell’s “Rosie” image was put to work selling war bonds and raising funds for the war loan program.

Rockwell’s original painting ended up in the hands of Mrs. P.R. Eichenberg of Mt. Lebanon. She won it in a nationally publicized raffle, though by war’s end it had been acquired by a company that manufactured (you guessed it) rivet guns and other pneumatic tools. (The model for Rockwell’s painting was 19-year-old Simsbury, Connecticut telephone operator Mary Doyle Keefe).

Tough copyright restrictions limited the use of Rockwell’s image, and the Saturday Evening Post-Rockwell partners themselves ran afoul of copyright woes. Thousands of posters depicting Rockwell’s cover girl were pulled off newsstands because they bore the unlicensed title “Rosie the Riveter.” The lawyers chose not to chance crossing songwriters Evans and Loeb, who, they figured, had the better claim to the name.

Miller reprised his Rosie character again and again. In April 1943, before Rockwell’s Rosie had appeared, he depicted Rosie at work with her rivet gun. Behind her, a colonial woman loads a musket. The poster’s bold caption reads: “It’s A Tradition With Us, Mister!”

The artist had clearly adopted Rosie the Riveter as a worthy subject, perfect for reinforcing his concept of empowered female workers and the “We Can Do It!” message inspired by employees at Westinghouse’s East Pittsburgh Works. In late 1942, these workers adopted a “Let’s Show Them!” slogan. At rallies and for news cameras, many of the 25,000 workers rolled up their sleeves and raised a clenched fist — the very pose adopted by Miller’s “Rosie.”

![20-year-old Naomi Parker [Fraley], working at the Naval Air Station in Alameda, Calif.](https://www.heinzhistorycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Naomi-Parker-Fraley.jpg)

Many people have wondered whether Miller’s Rosie was based on a real worker. Some have claimed that a photo of Naomi Parker, a young California woman war worker, inspired Miller. Others say Michigan aircraft plant worker Geraldine Doyle was the model. Rose Monroe was feted as the real Rosie and even appeared in a motion picture. But Miller’s Rosie, though inspired by Pittsburgh’s Westinghouse workers, was purely a figment of his fertile imagination. The same woman appears in his other work from that era. She represents the artist’s ideal of feminine beauty — with perhaps an extra measure of determination added in. As time passed, Miller’s Rosie became the most popular and recognized depiction of the American woman war worker.

So it seems that Pittsburgh’s war workers inspired Miller’s poster, which Americans embraced as Rosie the Riveter after hearing Kay Kyser’s radio rendition of the Evans and Loeb song. Rockwell’s popular magazine cover portrait famously satirized Miller’s poster and firmly fixed the idea of Rosie the Riveter in the minds of Americans.

During the war, American women entered the workforce, got driver’s licenses, and engaged in activities traditionally reserved for men. When the war ended, millions of women left the factories and the workforce, got married, and raised families. They took to these pursuits with the same energy and enterprise that characterized their war work. The Baby Boom resulted in a population explosion and the best educated, most prosperous generation that America — and the world — had ever seen. Women of the Boomer generation were as likely to go to college as their male counterparts. The daughters and sons of Rosie the Riveter and GI Joe ushered in the sexual revolution of the 1960s-1980s and major changes in women’s rights. Miller’s “We Can Do It!” poster was rediscovered and redeployed as a feminist icon. It now is one of the most recognized images in the world.

Pittsburgh was a keystone of America’s “Arsenal of Democracy,” and Pennsylvania produced more steel than all the Axis Powers combined. And, if that is not enough to swell a Pennsylvanian’s heart with pride, just know that Pittsburgh has a strong claim to “Rosie the Riveter,” whose “We Can Do It!” attitude shaped the world we know today.

Andy Masich is the president and CEO at the Senator John Heinz History Center.