Slavery was the root cause of the American Civil War. In fact, the inhumanity of slavery has been the cause of civil strife around the world for millennia. It takes the passage of time through generations to undo its pernicious effects. Here in the United States, we still live with its legacy. Issues of power and dominance, racial inequality and intolerance haunt us still and threaten to pull apart the fabric of our nation—a union that many had supposed permanently knitted together.

It should surprise no one that recent protests and counter-protests focused on Confederate monuments have revealed the many knots and flaws in the weave of our national character and constitution—woven in as compromises by the founding generation. Succeeding generations attempted to amend or rationalize the inherent contradiction of slavery embedded in the Constitution. Their patchwork fixes resulted in something neither true to the nation’s principles nor sustainable over the long run.

Rebellion and civil war inevitably came. “All knew,” Abraham Lincoln said in 1865, that slavery “was somehow the cause of the war.” Historians agree that slavery was at the heart of this conflict, but if one could go back in time and randomly interview Northerners and Southerners, white and black, about why they were fighting you would receive answers ranging from “freedom” to “Union” to “States Rights” to “equal rights” to “cultural survival.” It is likely that you would receive as many different answers as you would if interviewing an equal number of people about the Confederate monuments controversy and civil unrest today.

It is altogether fitting that we should engage in debate over the rights and protections promised by our republic of united states nearly 250 years ago. In 1776 the world began to awaken to the dream of liberty and democracy. It is somewhat surprising that the current retrospection and controversy over monuments honoring rebels did not occur during the recent 150th anniversary (2011-2015) of the Civil War, while our first African American president occupied the White House. Deemed too politically charged, no national sesquicentennial commission was empaneled and serious discussion of the war’s causes never took place. Perhaps the recent events are a delayed reaction, or maybe a new generation is finally awakening to its history.

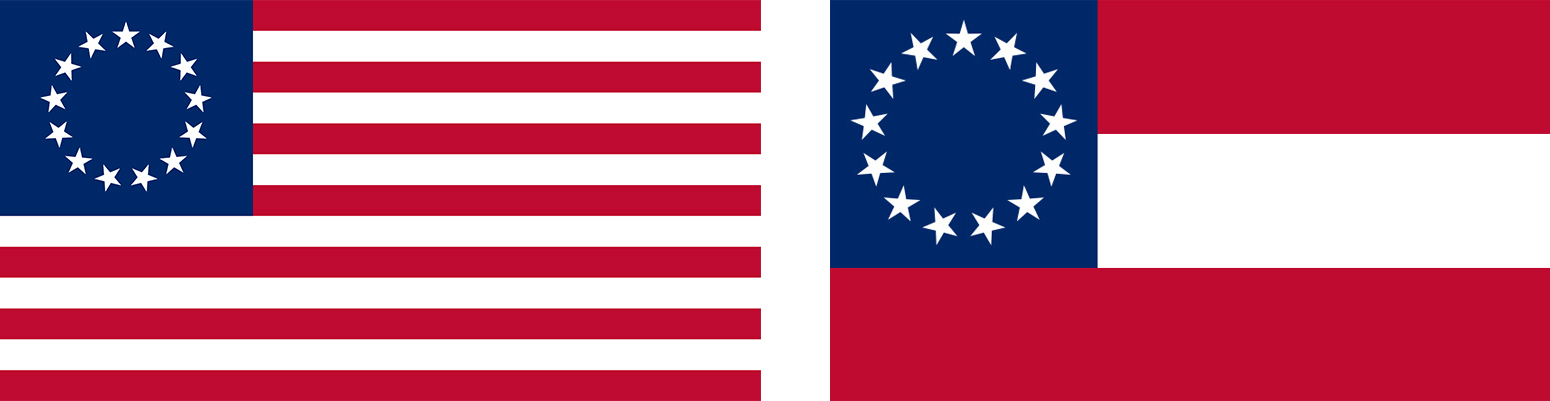

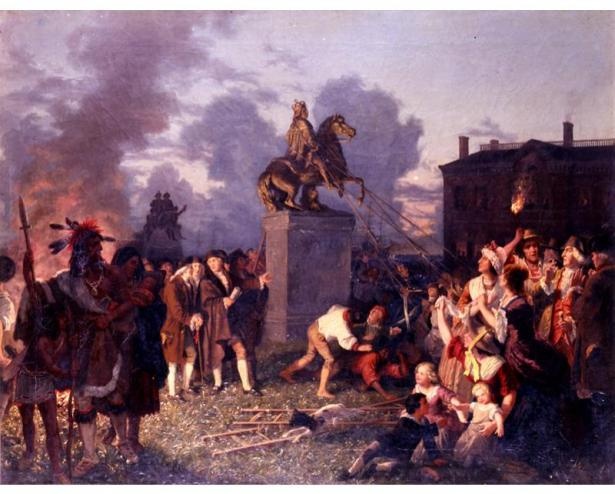

An understanding of our history is key to making sense of our past and making plans for the future. While the first American rebellion (1776) began with the pulling down of King George’s statue, the second rebellion (1861) saw the striking of the Stars and Stripes of the United States. The rebels, believing themselves to be continuing the traditions of their fathers, reconstructed the flag by re-sewing the stripes of red, white, and blue as the Stars and Bars of the Confederacy.

In both rebellions, citizens took to the streets and the rule of law was swept aside in favor of revolution. This is how it has worked for thousands of years when people feel disenfranchised or oppressed. Even Thomas Jefferson believed, “A little rebellion now and then is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical.” Hopefully, our society has sufficiently matured that we can avoid the violence that is often the companion of change.

(Pulling Down the Statue of George III, inspired by a painting by Johannes A. Oertel.)

The Civil War ended slavery in the United States and resulted in constitutional changes that supposedly guaranteed rights to all men (it would take another, less violent, revolution before women would be included) but did not end injustice to those formerly enslaved African Americans and their descendants. The people of the South who supported the Confederacy lost the war that killed or maimed more than a million and resulted in untold suffering among the civilian population, black and white, North and South.

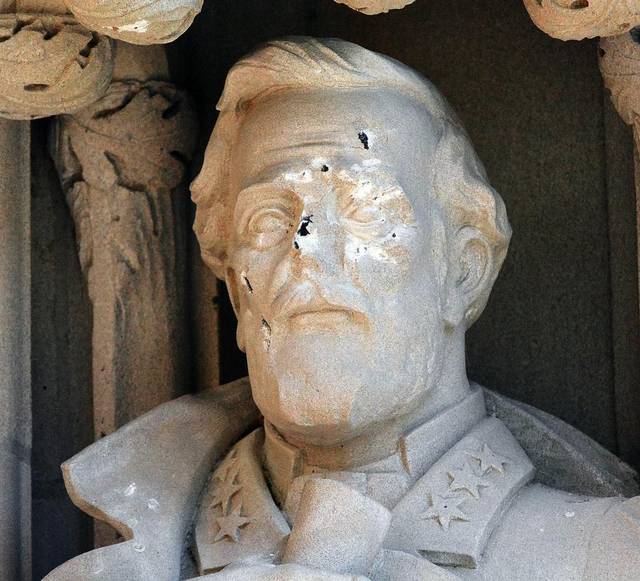

A pall of despair settled over the defeated South—where nearly every major city had been a battlefield. Hoping to reunite the country, Lincoln said, “let’em up easy.” He understood the need for a proud people to save face. Robert E. Lee shared Lincoln’s desire for peaceful reconciliation. Lee hoped to rejoin the union of re-united states and advised his countrymen against raising monuments or other displays of defiance. Frederick Douglass also warned against allowing rebel memorials to rise as such tributes might, “reawaken the Confederacy.”

After Confederate armies surrendered, the feared guerilla war never materialized, and the beaten South remained relatively peaceful. When the occupying federal armies withdrew, however, resistance grew anew. Perhaps let up too easy, Southern states passed “Jim Crow” (named for a racist stereotype from the pre-war years) laws ensuring segregation and inequality under the guise of “separate but equal” policies. Extralegal white lynch mobs terrorized the South’s black population in unbridled demonstrations of white supremacy, and the Ku Klux Klan reached new heights of influence.

Some fifty years after the war, in both the North and South, there was resurgent interest in memorializing the Civil War generation. In 1913, a great semi-centennial reunion of veterans, North and South, was staged at Gettysburg. Reconciliation and nationalism were the themes, and expressions of good will and comradeship prevailed. But few black veterans attended the nostalgic event.

As a highlight of the Gettysburg commemoration, Pennsylvania unveiled the largest monument—the largest in the country at that time. Statues sprang up from Maine to Florida, New York to Texas. Even more in the North than the South. Many of these were inspired by filial piety and a desire to honor the dead. No doubt many statues and monuments were politically motivated or supported by organizations with political agendas.

One hundred years after the war, white America once again turned its attention to the conflict. Books, films, TV programs, toys, reenactments, and still more monuments proliferated during the Civil War Centennial. In these memorials, the role of slavery was often left out, and the Southern narrative of the “Lost Cause” seemed to predominate.

Southern historians lionized Lee as a paragon of virtue and symbol of the nobility of the South’s struggle for independence. The alternative facts they presented seemed to be turning the tide in the war for the memory of the Civil War. Even Northerners and white members of the congressionally appointed Civil War Centennial Commission chose not to dredge up the painful memory of America’s slave past.

But African Americans could never forget. The revolutionary Civil Rights Movement would not allow the lingering institutionalized crimes and injustices of the Jim Crow era to pass unnoticed, and Congress finally acted to effect meaningful change during the “Second Reconstruction” of the 1960s.

In today’s America, civil dissent can be a good thing. Civil discourse characterized by empathy can be unifying and make us stronger. An understanding of history and civics is also essential. It is time for all Americans to revisit our nation’s motto, “e pluribus unum” (out of many, one). But it is time to focus less on the pluribus and more on the unum. We are now one people. This does not mean we need forget our roots and the paths that brought us together. The United States was never really a melting pot of assimilated people. A magnificent tapestry woven of millions of unique threads might be a more apt analogy.

If we have the moral fiber, will, and patience, we can together re-weave the fabric of our nation. We can make it the tapestry that it has always aspired to be, composed of many stories and admired by all the world.

Our national loom may require some retooling. The warp and weft of our country has changed over time, and some of our dyed-in-the-wool convictions will have to change as well. Confederate monuments are painful reminders of America’s slave past. How do we forgive the unforgivable? At the same time, these memorials reflect Southern pride. Is there a way to reconcile the two? The Confederates lost the war. Perhaps their monuments should fall to the victors’ hammers and ropes as has been the tradition for millennia. Sojourner Truth, forty years a slave, said, “I am for keeping the thing going while things are stirring. Because if we wait till it is still, it will take a great while to get it going again.”

What would Lincoln say of the Confederate statues? Perhaps he would advise, “let’em down easy.” But now that the monuments have begun to fall, do we “keep the thing going” or allow unreconstructed America to cherish its imagined past? There is right and wrong—and then there is getting along.

Following thoughtful deliberation, some monuments in public places should be reinterpreted, relocated, or permanently removed. In any event, the will of the people must prevail. That is how democracy works. As the model for democratic republics, we the people of the United States owe it to our forebears, our heirs, and the world to get it right.

Andy Masich is the president and CEO at the Senator John Heinz History Center.