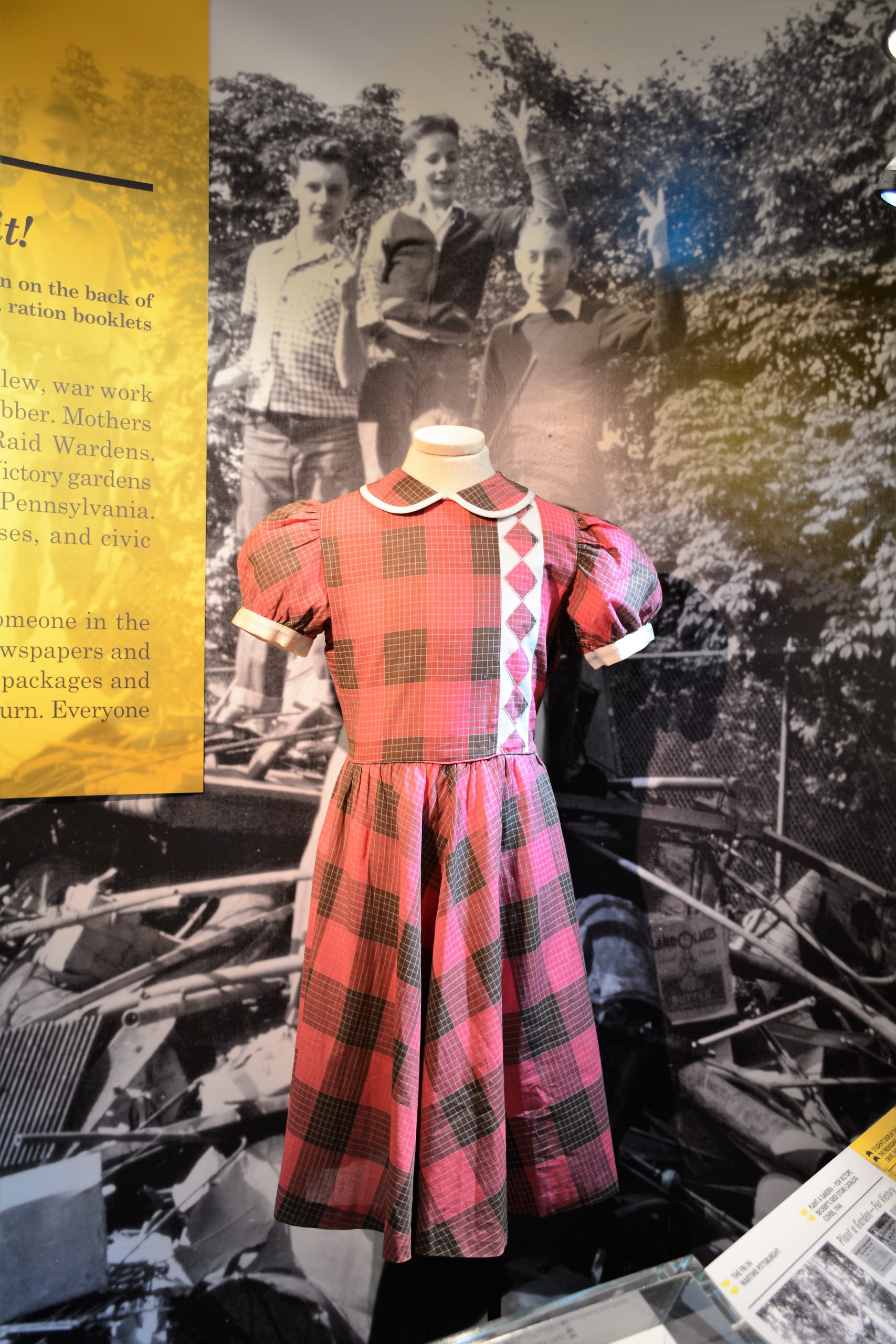

With the History Center’s traveling exhibit “We Can Do It: WWII” returning to Barensfeld Gallery, it seemed a good time to celebrate the upcoming Halloween holiday by looking back on how this haunting season was experienced during World War II. In fact, Halloween in the war years laid the groundwork for what the holiday became during the Baby Boom.

Pranks Discouraged

A previous Making History blogpost explored the earlier history of Halloween when it was known more for tricks than treats. This tradition presented a special challenge by 1942. While officials recognized that celebrating Halloween would help morale, they were concerned about destructive pranks taxing the resources of communities with men away at war, people learning to live with rationing, and everyone on edge. Some Pennsylvania towns even banned the wearing of masks by adults due to sabotage fears, threatening violators with arrest. In Pittsburgh, Juvenile Court Judges reminded eager youngsters that previously fun gags such as soaping windows, stealing gates, and puncturing tires were not amusing when materials such as the fats in soaps, metal, and rubber were needed for the war effort. Even ringing doorbells was discouraged: it ruined the sleep of war workers and slowed crucial munitions production. As an article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, with the ominous heading “Halloween Pranksters Aid Foe,” put it on Oct.29, 1942: “Uncle Sam sorrowfully warned his juvenile nieces and nephews that the only way they could go hobnob with the hobgoblins this All Hallow’s Eve was to stay at home and make faces at each other.”

Making Mirth and Making Do

So, what were young ghosts and goblins to do? Instead, parents, teachers, and other adults were urged to organize parties and help steer young minds toward activities that kept the holiday “safe and sane.” Youth groups such as the Junior Commandos pledged to celebrate the holiday by avoiding the damage and waste of previous years. Cleverly furthering their wartime support while also offering a rationale for some good old-fashioned fun, the Commandos suggested that children should of course still enjoy the house-to-house festivities of “beggar’s night,” but collect scrap metal at the same time. (We can only envision how they would have carried all of that!)

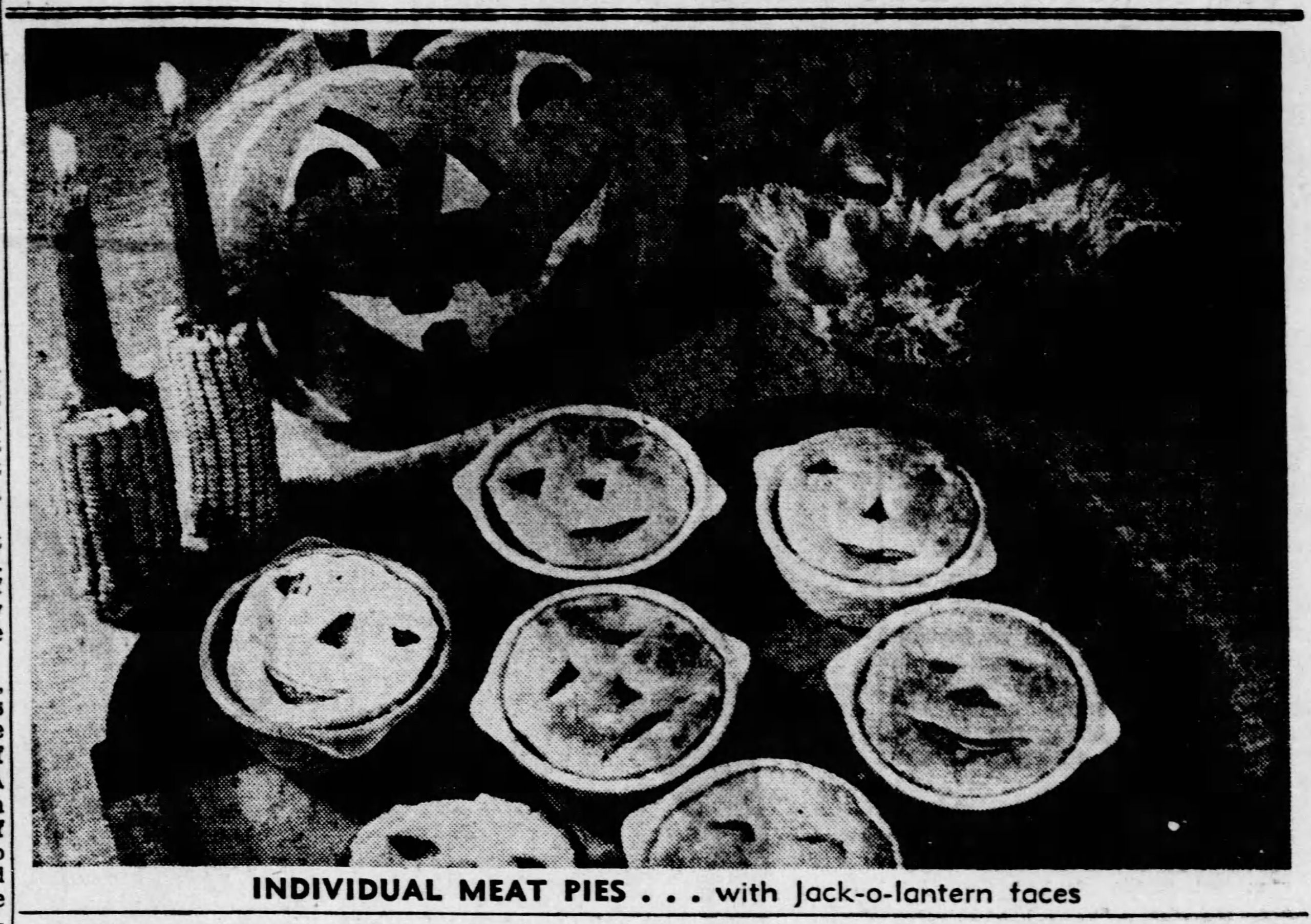

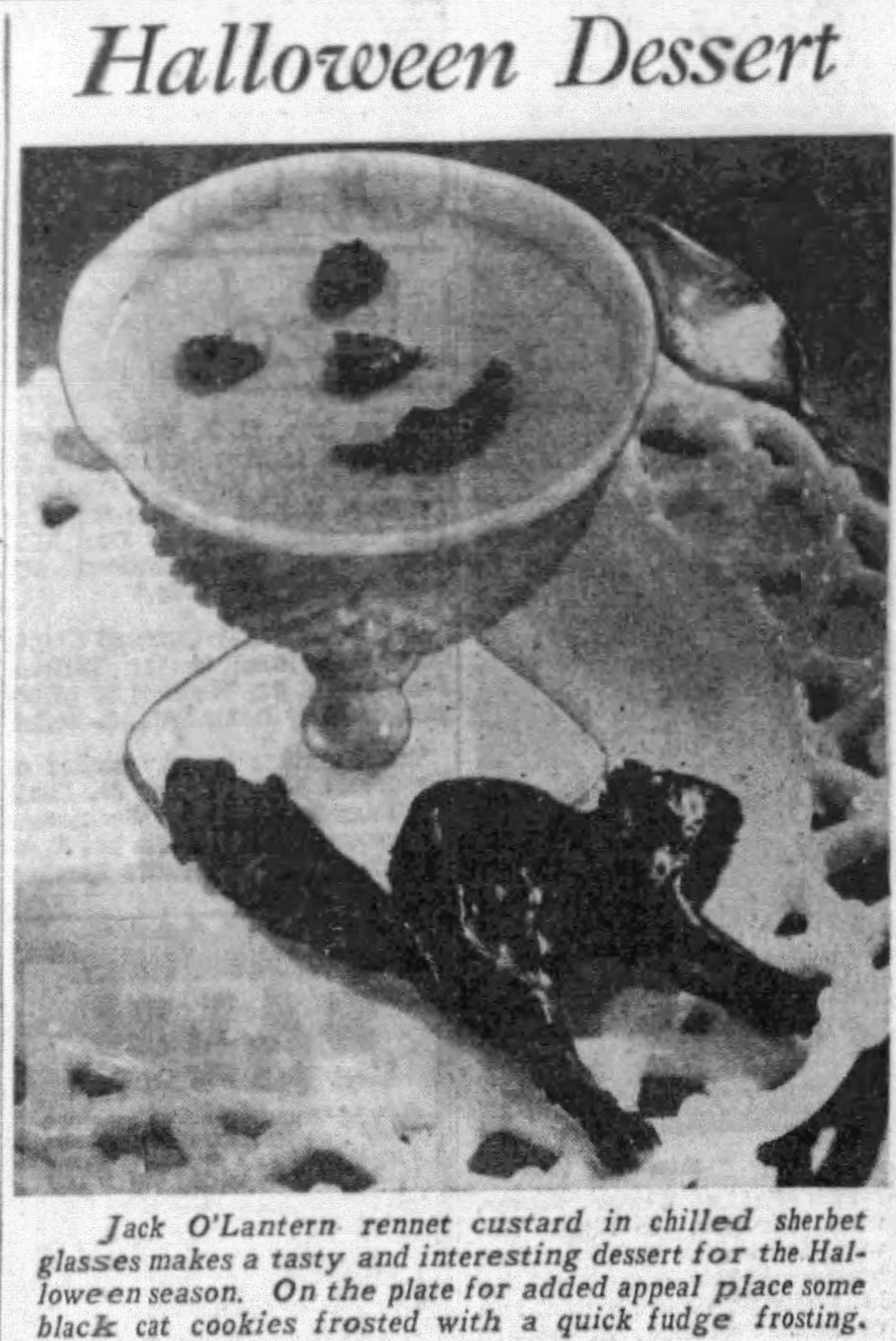

More common were plans for activities and recipes that encouraged families to celebrate Halloween at home or in neighborhood events, which would also save gas. Food and women’s section editors for the local newspapers offered ideas and helpful hints. Many recipes created enticing and spooky party menus that nonetheless reflected the realities of wartime rationing. “Black Magic Chocolate Tarts,” a Pittsburgh Press favorite, were made with unsweetened chocolate and sweetened evaporated milk, no extra sugar needed. Grinning miniature meat pies used economical cuts of diced meat along with onion and a can of vegetable soup. Molasses made its way into everything from cookies to taffy. Pulled black walnut taffy did use brown sugar but relied on another ingredient that could be gathered and processed by households on their own when black walnuts were a more familiar fall staple than they are today. Also less familiar for modern readers was the “Jack O’Lantern rennet custard,” a chilled, orange-flavored dessert made partially from an enzyme (rennet) typically used in cheese production but also found in packaged desserts such as Junket, similar to Jell-O and tapioca.

Add a Spooky Accent

In all these examples, creative cooks were encouraged to enhance the dishes with decorative flourishes that emphasized the spooky season. This included cutting pumpkin faces in meat pies, constructing silhouettes of witches on tarts, and using cut up bits of prune to craft a smiling face in the rennet dessert. Other examples suggested that cloves could create smiling faces in lemons for a punch bowl, emptied oranges could be cut and used for miniature Jack-O-Lanterns, and that black cats could be fashioned with a prune body, ripe black olive head, and raisins for legs and tail. (In the interest of history, it should be noted that this writer tried the latter and it didn’t work that well.) One must wonder when those busy war workers found time to do all that decorating.

Looking to Halloween’s Future

The doom and gloom of Halloween 1942 ebbed in later years as Americans grew accustomed to the wartime home front atmosphere. But the emphasis on prank-free celebrations and ration-friendly recipes continued. (Rationing did not end with the war; sugar was rationed until 1947.) These years accelerated a change that had been in development since the 1930s, when the damaging aspects of the prankster and adult mummer, or carnival, tradition converged with growing concerns over issues such as juvenile delinquency and child development. The patriotic prank-free Halloween of World War II helped cement the child-focused version of the holiday that predominated as the war years turned into the Baby Boom. New suburban developments filled with children did everything in their power to keep the holiday “safe and sane.”

Of course, there were always outliers, and certain amounts of soap, corn, toilet paper, plastic forks, and other prankster supplies continue to make their annual appearance in Western Pa. But changes ushered in by the war lasted for the next fifty years, until those same Baby Boomers helped change the course of Halloween again in the 1990s, transforming it into a holiday shared by adults and children and one of the most profitable seasonal celebrations nationwide.