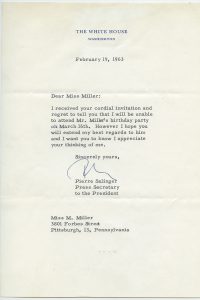

When Gus Miller turned 75, his daughter and business partner, Myrtle Mae Miller, decided to turn his birthday into a public event. She invited scores of his friends and loyal customers, including bartenders, bankers, and policemen, to stop by his newsstand on Forbes Avenue for a piece of a cake. At that point, Miller had become a neighborhood institution in Oakland, known not only for his long-running store but also his decades of service as chief usher at Forbes Field. This birthday tradition continued in the years to come, with the guest list growing to include local politicians and reporters, who dutifully covered the celebrations for their papers, sometimes referring to Miller as “Oakland No. 1 Citizen.” Tongue-in-cheek invitations were sent to national figures including the Postmaster General, the Secretary of the Army, and even the President of the United States. Well known for his playful sense of humor, Miller decorated his store with their declining responses (a film of Miller’s 80th birthday day can be seen is available on the History Center’s YouTube channel).

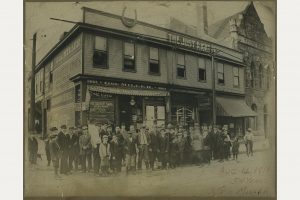

Myrtle Mae also made sure to invite members of the Pittsburgh Pirates organization, from owner John W. Galbreath to the groundskeeper Eddie Dunn, though many could not attend due to Miller’s St. Patrick’s Day birthday coinciding with spring training. Miller’s life had been closely linked with the Pirates since he was a boy, when his newsboy earnings bought tickets to games at Exposition Park. By the time he was a young man, Miller had secured his job as chief usher, a position he held for another 42 years. When the Pirates traded the flood-prone banks of the Allegheny for the up-and-coming Oakland neighborhood in 1909, Miller followed, opening his newsstand a couple of blocks from Forbes Field at the intersection of Forbes and Oakland avenues. He soon bought a house on the next block over, meaning that, whether at work or at home, Miller could be found within a three-square block area in Oakland.

Proud of never taking a sick day, Miller claimed in 1956 he would work at his store until he was 100. Just a few years later, however, Miller’s attitude changed. “When Forbes Field goes, that’s when I quit,” he said in a frontpage Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article that referenced the University of Pittsburgh’s efforts to purchase properties in Oakland. By the fall of 1958, the university may have reminded some of the eponymous monster from “The Blob” (then playing in area movie theaters) as it extended into the surrounding neighborhood, swallowing up prime real estate as it went. It had already acquired the historic Schenley Hotel and Schenley Apartments, repurposing them into a student union and a residential hall, respectively. As the culmination of these expansion plans, the university purchased Forbes Field in November that year for two million dollars, agreeing to lease the park back to the Pirates until a new stadium could be built.

The sale raised objections from Oakland’s merchants, who feared losing customers after the Pirates departed the neighborhood. These concerns are echoed in some of the letters sent to Miller, which are now part of the Heinz History Center’s Detre Library & Archives’ Gus Miller Papers. “During your sixty-four years of business you have remained a solid citizen and stalwart businessman despite the onslaught of the automobile, electricity, Kaiser Wilhelm, prohibition, stock market crash, gangsters, depression, Hitler, World War II, television, and automation,” wrote lawyer Peter Schwartz. “We congratulate you with the knowledge that you will weather the current crises of planning and redevelopment just as you have so bravely come through in the past.”

James Waldo Fawcett, who served on the board of the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania (the History Center’s forerunner, then located in Oakland) took a more histrionic tone in his message. “This may not be understood or appreciated by certain strangers who have come among us recently and now are engaged in a campaign to destroy our Oakland community. If these alien intruders were to have their way, you and we would be scattered afar. Our homes and our businesses would be demolished and removed from the face of the earth.”

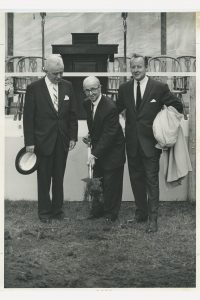

Despite being the catalyst behind the university’s redevelopment of Oakland, Chancellor Edward H. Litchfield enjoyed good terms with Miller, receiving annual invitations to Miller’s parties. Photographs in the Gus Miller collection also depict the shopkeeper joining Litchfield for the groundbreaking of new dormitories and the Frick Fine Arts Building in the early 1960s. Litchfield likely recognized the public relations benefit of having a leading member of the neighborhood’s business community wielding a shovel at these events.

Ultimately, Miller did not live to see his beloved Pirates sail back to the North Side in 1970, though his newsstand and name survived Forbes Field by many decades. Miller continued working at his store until shortly before his death in 1967. Myrtle Mae Miller continued the newsstand until selling the business and retiring in the mid-1980s. Succeeding owners of the newsstand continued to use the Gus Miller name well into the 2000s, a testament to the enduring legacy of “Oakland’s No. 1 Citizen.”

About the Author

Matthew Strauss is the director of the Detre Library & Archives.