What do flight pioneers Amelia Earhart, Buzz Aldrin, and Neil Armstrong have in common? How about Pittsburghers H.J. Heinz, Mary Roberts Rhinehart, and Edgar J. Kaufmann? They’re just a few of the many famous Americans with German ancestry. From Heinz ketchup to Iron City Beer, Pittsburgh just wouldn’t be the same without its German roots.

Today is a good day to celebrate that heritage. Oct. 6 is National German American Day.

President Ronald Reagan first proclaimed the day in 1983 to honor the 300th anniversary of the founding of Germantown, Pa. This community near Philadelphia was settled by German Mennonites on Oct. 6, 1683, the first organized German settlement in America. The day was sporadically celebrated in the 1800s, but never became a national event. After Reagan drew attention to it, German American groups spent years lobbying and succeeded in getting the official observation approved in 1987.

Early Settlement in Pittsburgh

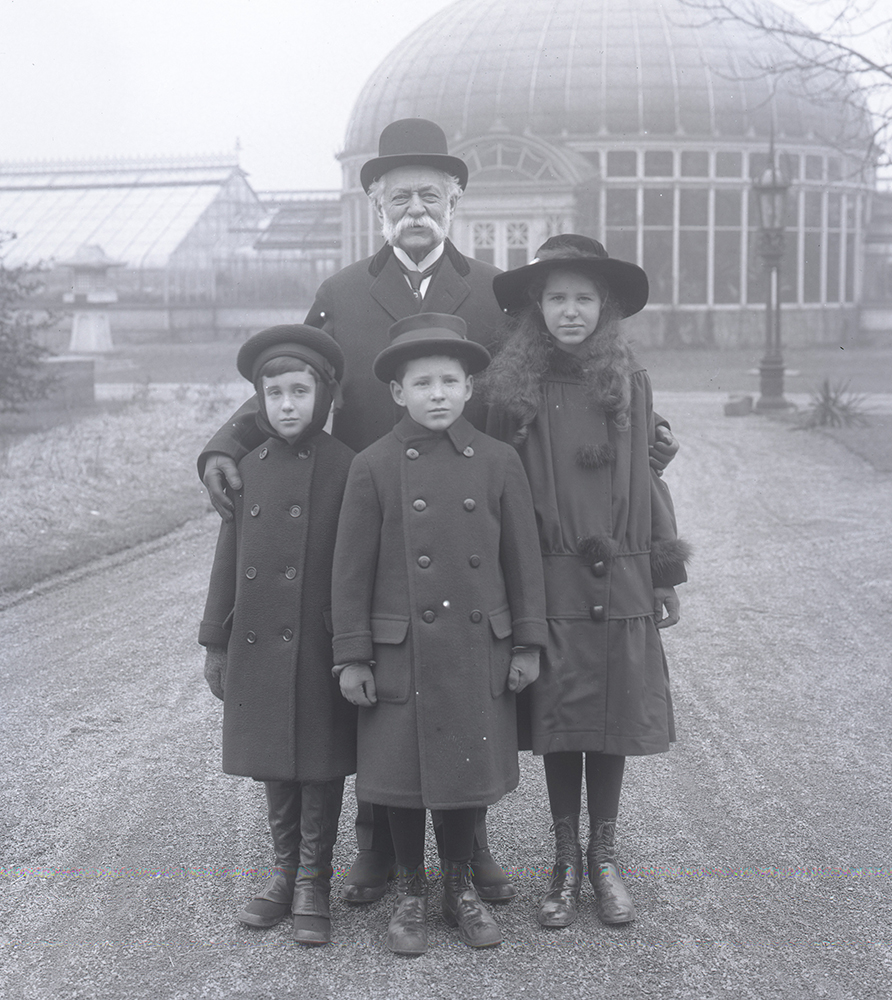

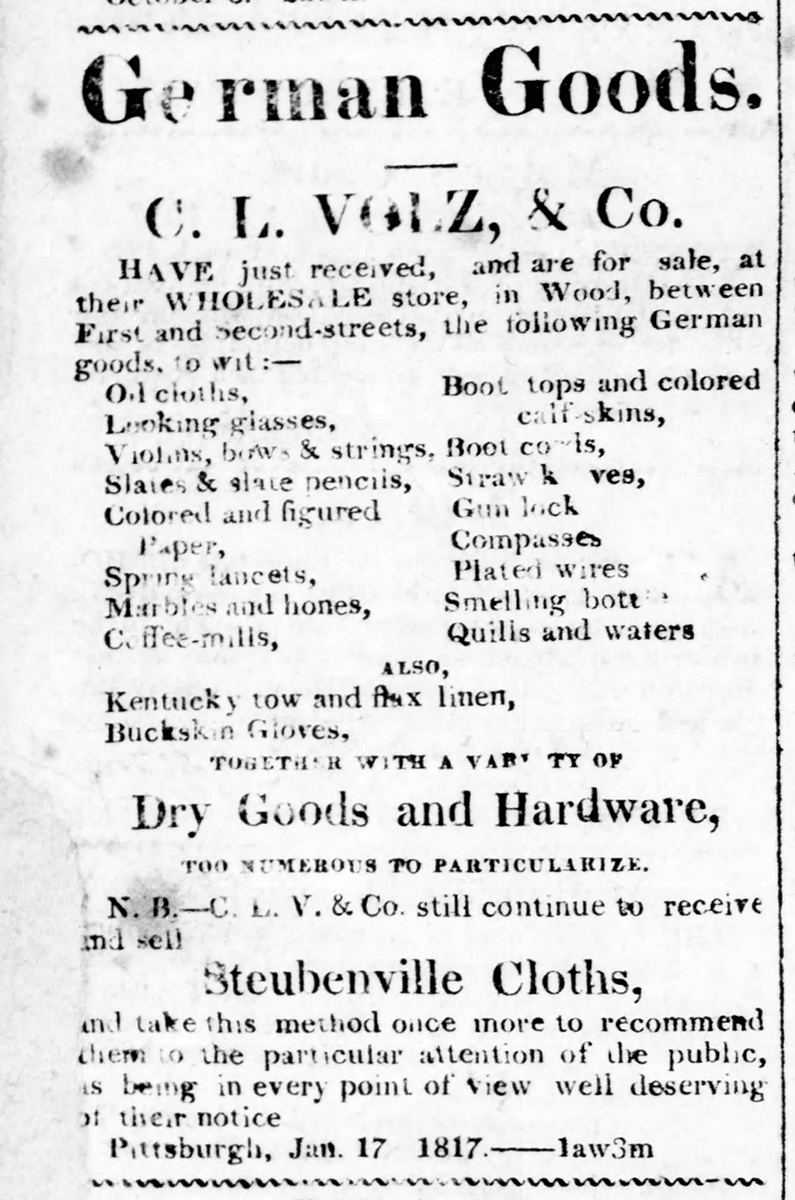

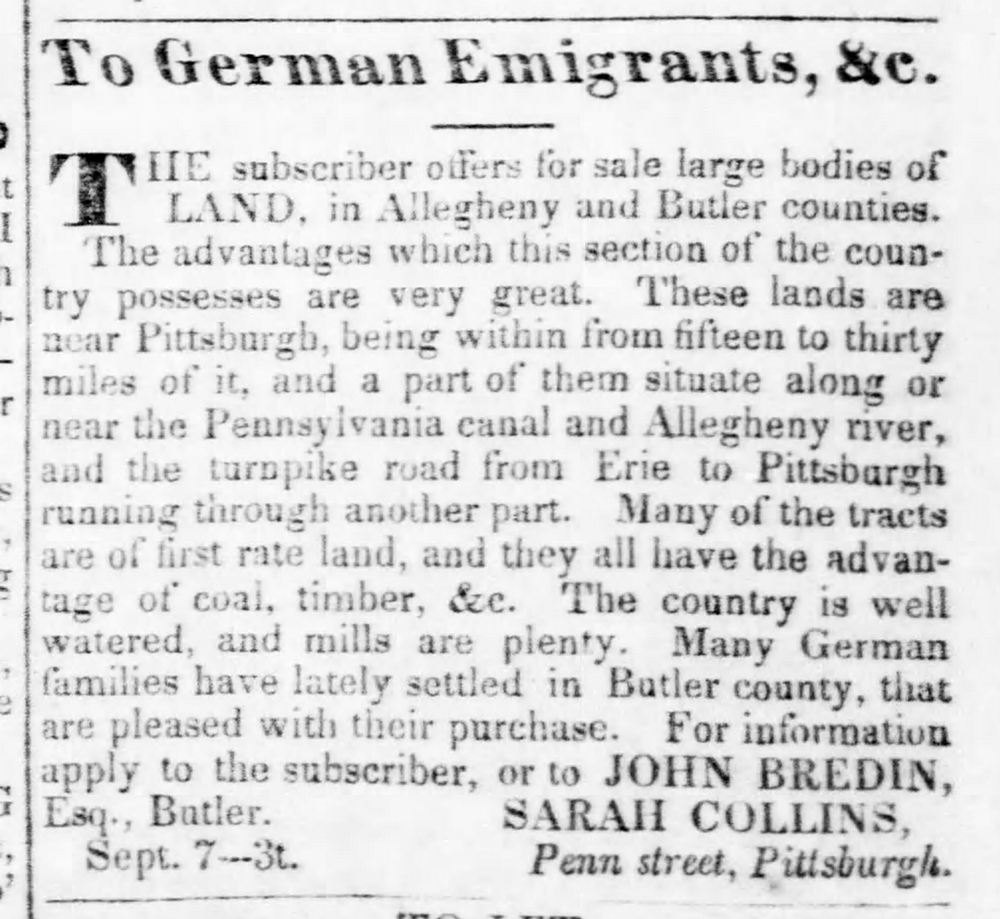

Today, German Americans still make up the largest European ancestral group in Pittsburgh. While Benjamin Franklin once complained that this “alien” population would “Germanize” Penn’s colony, western Pennsylvanians encouraged German settlement. German immigrants made their way west by the 1700s and established an active presence in Pittsburgh. By the early 1800s, local newspapers routinely carried ads for German merchants. German immigrants sought indentured servant positions here.

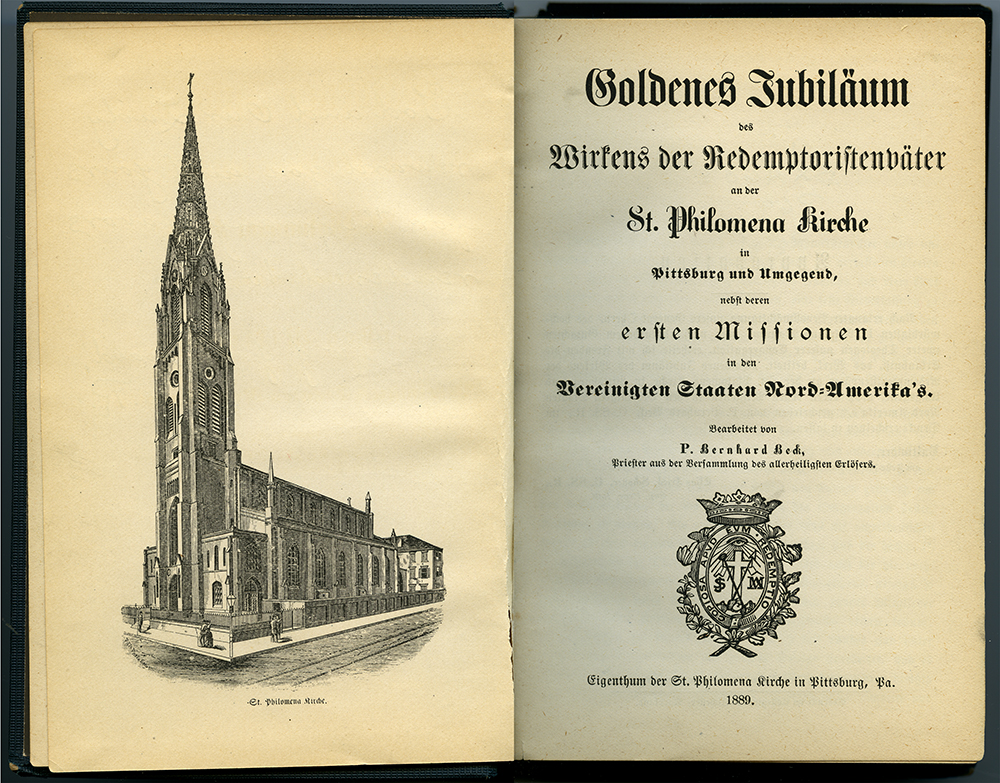

By 1839, the first ethnic German church parish opened in Pittsburgh and German Jewish immigrants founded the community’s first synagogue. Pittsburgh schools taught German. The Pittsburgh Gymnasium (in the 1800s that was a school, not a sports center) noted that knowledge of the German language was “indispensably necessary for men of business in this community.”[1] Among those German-speaking citizens who arrived in the 1840s were John Henry Heinz and Anna Margaretha Schmidt, parents of Henry J. Heinz, creator of the H. J. Heinz Company.

A Proud Heritage

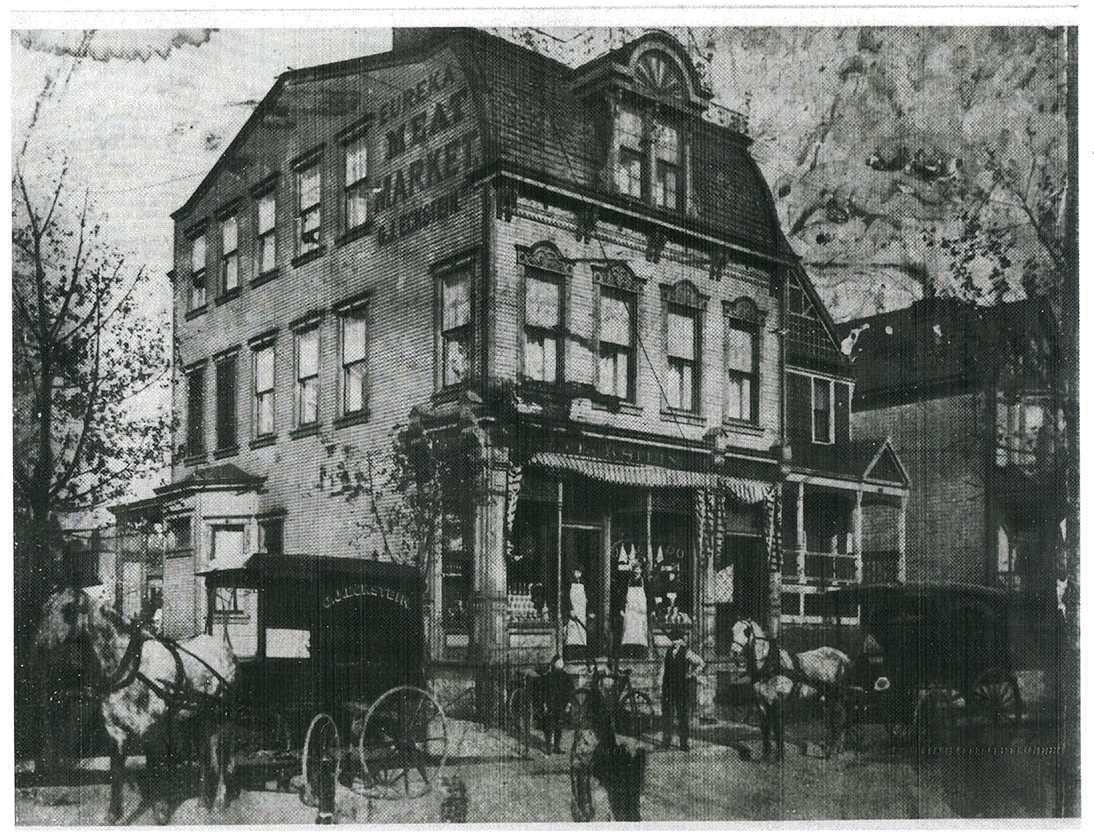

Pittsburgh’s German community was an active segment of the city’s civic life. It ran much of Pittsburgh’s beer and saloon trade and established an especially strong presence in Allegheny City, in the area known as “Deutschtown.” Between 1834 and 1942, Pittsburgh always had one and sometimes two German language newspapers. German singing societies grew popular in the 1850s, and clubs rose across the Ohio and Mon River valleys. These “Maennerchor” (men’s choirs) preserved German song traditions and helped new German immigrants adapt to this country. One of the membership requirements? For most, members needed to become citizens of the United States.

Which Side are You On?

German groups were always sensitive to the question of loyalty: Were they truly American, or were they still German? In August 1890, during one local discussion about reviving “German Day,” planners announced in the Pittsburgh Dispatch that they had chosen Oct. 6 as the date. But they stressed that the celebration would “refrain from indulging in any demonstration that is totally confined to their own nationality.” Organizers made it clear that they were “Americans and want to be associated with American celebrations.”[2]

German communities across the country expressed similar concerns. In some places, “German Day” was acknowledged not in October but incorporated into other holiday celebrations such as Labor Day or the Fourth of July.

Impact of World War I

Questions about German-American loyalty grew stronger in the early 1900s. The expanding American temperance debate placed blame for the alcohol trade on “foreigners” such as the Germans, who dominated the national beer industry. Even worse, the United States’ entry into World War I in 1917 focused new suspicion on a group that had exerted great effort to maintain their own language and social clubs.

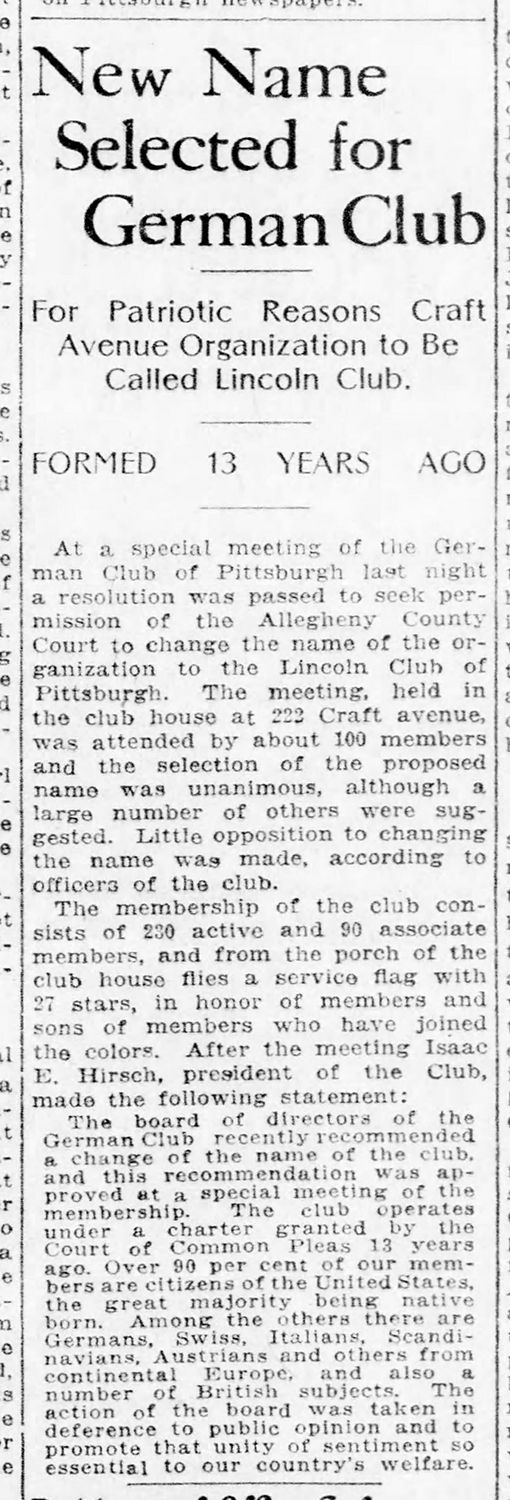

By early 1918, tensions erupted into a full-blown wave of anti-German sentiment that swept the nation. Groups such as the American Defense Society called for a ban on everything German, from teaching the language to licensing German clubs.[3] Pittsburgh newspapers favored eradicating the menace of German influence and ran dramatic articles condemning the “tentacles of the German octopus.”[4] In September, a leader of one of Pittsburgh’s pig iron and steel brokers, Banning, Cooper & Company, was arrested for having expressed pro-German thoughts. Members of local German Clubs were questioned by agents of the Department of Justice.[5]

Changing Names

Such events prompted German clubs across the country to minimize their Germanness. They began emphasizing their identity as American clubs. A singing club in Baltimore changed its name from the “Germania Maennerchor” to the “Metropolitan Club of Baltimore.”[6] The German Club of Pittsburgh became the “Lincoln Club” (this did not prevent members being questioned by government officials).[7] That not all Pittsburgh groups made such changes was a testament to the city’s deep German roots.

What started during World War I essentially continued through World War II. While some German clubs continued to celebrate their heritage, the activity was quieter. Many sought to avoid drawing attention to themselves. Some families stopped teaching the German language to the next generation.

Heritage Reclaimed

Just as political and diplomatic issues created incentives for minimizing German American heritage, the same factors also helped to revive it. After World War II, the American airlifts to Berlin during the Cold War in 1948-1949 softened public sentiment. German contributions to the Space Race, while not without controversy, likewise added a new dimension to the story. As the Cold War escalated and the Soviet Union become the primary villain, appreciation for German American heritage regained a foothold along with the importance of West Germany to defense initiatives such as NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization).

When President Ronald Reagan first announced plans for the celebration of the 300th anniversary of the first German settlement in America, he did so in a speech before the Bundestag (the German parliament) in Bonn, Germany, speaking directly to the German people.** This same anniversary also marked the first year that the city of Pittsburgh sponsored its own Oktoberfest in 1983.[8] By the time National German American Day was officially added to the calendar in 1987, the Berlin Wall was just two years away from its final fall.

** The content of President Reagan’s Bonn speech can be read online.

[1] The Pittsburgh Gazette, December 15, 1840.

[2] “German Day celebration,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, August 22, 1890.

[3] “Judge them by their fruits,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, April 5, 1918.

[4] “Tentacles of the German octopus in American uncovered,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, January 12, 1918.

[5] “Wealthy man is arrested as German agent,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 28, 1918.

[6] “To drop German name,” The Evening Sun (Baltimore), May 29, 1918.

[7] “New name selected for German club,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 9, 1918.

[8] “City sponsors first Oktoberfest,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 7, 1983.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.