Homestead, Pa. has an extraordinarily rich sports history. Traditions of success in early professional football, women’s swimming, basketball, and baseball frequently filled Pittsburgh’s sports pages. Through the 1940s, though, town and company adult sandlot baseball teams were a more central point of pride and entertainment at a time when America’s pastime was far more popular than any other sport. Across the state, this baseball team was often a coal mine or steel mill team, and in Homestead, Carnegie Steel’s Homestead Steel Works often sponsored the team. Generations later, as old, forgotten sandlots were redeveloped, the communal memories of many lost stories and unsung heroes unfortunately faded. Two such exemplary players for the Homestead Aces, local stars of a bygone era, were Homestead steelworkers and brothers of Hungarian descent John (1904-1995) and Joe “Mutt” Asmonga (1906-1983).

Image: Homestead Aces, Greater Pittsburgh District Champions, 1928. Left to right: Jack Fertig manager, T. Martin business manager, Joe Kristan, Steimer, John Asmonga, McGuigan, Schirra, Dober, Capp boy mascot, Henderson, Gallagher boy mascot, Neville, Renquist, Forquer, Bullion, Garvey, Rudman, St. Ribar d.c., M.T. O’Rourke treasurer. Detre Library & Archives, Gift of Linda Asmonga, in memory of her father-in-law John A. Asmonga.

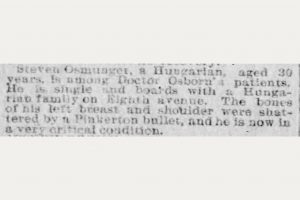

The Asmonga (a last name seen in a myriad of spellings) brothers’ playing days can be better understood by first examining Homestead’s previous steel industry and baseball history. In 1850, Abdiel McClure began selling his family’s Amity Homestead. He sold a portion of the land about seven miles southeast of Pittsburgh and bordering the Monongahela River in 1872, which was officially founded as Homestead in 1880. Growth exploded as the Homestead Steel Works was established in 1881, and Andrew Carnegie purchased the mill in 1883. The first newspaper mentions of Homestead baseball teams appeared in 1889, but trouble soon brewed as union steelworkers were infamously locked out. One of the first workers shot, non-fatally, was Stephen Aszmongya (John and Joe’s uncle), in the Homestead Steel Strike of 1892. Violent clashes between striking workers and outside Pinkertons eventually resulted in ten deaths, and roughly 60 people were wounded. Then Alexander Berkman almost succeeded in assassinating Carnegie’s partner, Henry Clay Frick. Even Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher and Homestead native Mark Baldwin became involved as he was arrested as an alleged participant in the riots and accused of distributing two Pinkerton guns to fellow demonstrators. Though the union was defeated and conditions soon worsened, this was a prideful battle in the fight to improve workers’ rights, safety, and pay.

Nationwide and in Homestead, management’s support of company sports teams in the 1890s and thereafter helped to foster a bit of unity as the labor movement fought for change. Braddock’s Edgar Thomson Works and Homestead Steel Works manager Charles Schwab himself publicly offered good jobs at his mills for good ballplayers (Feb. 13, 1898, Pittsburgh Press, pg. 7). In 1898, Homestead’s leading team signed Rube Waddell, who, as a teenager, lived in Butler County and would go on to star for the Pittsburgh Pirates and later set the major league single-season strikeout record in 1904. Also in 1898, Andrew Carnegie founded the Carnegie Homestead Library (which still serves the community), and soon thereafter, the Homestead Library and Athletic Club which fielded strong baseball and football teams.

By 1900, Carnegie’s Homestead Steel Works was the largest and likely the most productive steel mill in the world. The next year, J.P. Morgan financed the merger of Carnegie Steel with Federal Steel and National Steel to create U. S. Steel Corporation. In the subsequent decades, the Homestead Steel Works team remained successful, as George W. Busch, a longtime Homestead baseball booster served as its president. Another team that fielded some Homestead Steel Works players, the Homestead Grays, began play in 1911. Led by Cum Posey, they went on to become the dominant Negro Leagues team of the 1930s and 1940s.

Image: Prior to the Asmonga brothers’ playing days, the 1914 Homestead Steel Works team posed with president George W. Busch at center. Left to right: Joe Popp OF, Foy C, Austin SS & Capt., Bart?/Burst? 2B, Cloherty 2B, Rushe P, Orris? 1B, Martin Secretary, President George W. Busch, Carrick mascot, Wigmon Manager, Hoffman OF, Ellis P, Aston 3B, Baird LF/IF, Barthold C, Kaufold OF, and Eliker P. Detre Library & Archives, Gift of Trilby Busch.

While growing up in Homestead, John and Joe Asmonga lived with two older brothers and two sisters. While attending Homestead High School in the early 1920s, John coached a grade school baseball team called the “Pawnees Black Circle” and played varsity soccer for the Homestead High Steelers. Starting at the age of 22, he became a star pitcher for the Homestead Aces, the leading team of the era, and played alongside his brother Joe, who also pitched and played center field. In studying the available box scores of the time, it is now difficult to distinguish the two brothers, as most often only their last names were listed and they shared the same first initial “J”. By family accounts, John often maintained a near .400 batting average and a “J. Asmonga”—possibly even both brothers—played for several other community teams, perhaps as proverbial “ringers”.

Image: Jack Fertig’s Homestead Aces Greater Pittsburgh District Champions 1928 and 1929. Left to right: M.J. O’Rourke Secretary, C. Henrickson Scorer, G. Bingham, Josey Stemier, A. Requist, J. Mach (seated teen), A. Steimer, A. “Skipper” Douds, C. Kuhns, E. Anderson, J. Henderson, G. Kirk, J. Simko, H. Kelly, John Asmonga, Buddy Scott (seated boy), J. Neville, C. Forquer, J. Garvey, Paul Mach business manager, Jack Fertig manager, and Lou Walker (inset). The Aces this year wore seemingly identical uniforms and hats to the Pittsburgh Pirates, which were likely bought at Pittsburgh Sports Shop, Sixth Avenue downtown. Detre Library & Archives, Gift of Linda Asmonga, in memory of John A. Asmonga.

Aside from the more skilled and famous Homestead Grays, the Asmongas led the Homestead Aces, a prominent and successful community sandlot baseball team, from 1927–1933. The Aces won league championships in 1928 and 1929. Their league went by various names; the Greater Pittsburgh League, the Pittsburgh Spalding League, Tri-Boro League, or Press League. In 1931 and 1932, the Aces competed in the West Penn League, and sometimes the team is informally and simply called the steel workers, though sponsorship or the connection to the mill is unclear. The Aces were managed by Jack Fertig from 1927 to about 1932. They played around the city at fields such as Homestead Park, Edgar Thomson Park (Braddock), Hartman Park (East Liberty), Ammon Field (Hill District), Harlan Field (McKees Rocks), and West Penn Park/Field (Polish Hill). In 1940, Fertig, as superintendent of Munhall’s public works department, facilitated improvements to the stands at the new West Field, which was renovated in 2016 with funding from Homestead native Bill Campbell.

Pitching for the Aces, John and Joe played in games against several Pittsburgh sports legends. On Aug. 27, 1929, the Aces faced the Pittsburgh Crawfords, who started a 17-year-old catcher named Josh Gibson alongside Harold Tinker and Charles “Teenie” Harris, the future acclaimed Pittsburgh Courier photographer. Gibson went on to become one of the greatest power hitters of all time while playing with the Crawfords and the Homestead Grays (from 1930–1931, 1937—1940, and 1942—1946). Both “J. Asmonga’s” appeared in the boxscore, one pitching and one in center field. And on Aug. 10, 1934, an unnamed Asmonga brother struck out six batters, homered and doubled for Mt. Oliver against the J.J. Vaughans, who were captained by their 33-year-old left fielder Art Rooney. “The Chief” founded the NFL Pittsburgh [football] Pirates the previous season, and the team was renamed the Steelers in 1940.

Later in life, John and Joe excelled in bowling and frequently appeared in Pittsburgh newspapers amongst tournament leaders. Brother Lou enjoyed “homing” as a member of the West Mifflin Pigeon [racing] Club. Still another brother, Steven, had a son named Don who soon occupied sports headlines. Don Asmonga (1928—2014) played high school baseball, basketball, and football for Homestead. Under the tutelage of legendary basketball coach Chick Davies, who took a hiatus from Duquesne University to teach and coach at Homestead, the Steelers won the state championship in 1946. Afterwards, Don played professional basketball and then pitched in the Boston Red Sox minor league system until he suffered an arm injury. He briefly signed on with the Pittsburgh Pirates organization but by the end of 1953, Don became a Baltimore Bullet and played in seven career NBA basketball games. In 1954, Don played in the Greater Pittsburgh (baseball) League, where his uncles, John and Joe, played decades prior. Don’s greatest impact, however, was as a longtime coach at Belle Vernon High School, highlighted by his Leopards’ 1967 WPIAL baseball sectional title and the 1978 WPIAL basketball championship title.

John Asmonga’s son, John J. Asmonga, worked in the mill as a third-generation steelworker before becoming a commercial interior designer and an instructor in art and design. He passionately studied local steel history, researching and memorializing the 1892 Battle of Homestead with his wife, Linda, and the Battle of Homestead Foundation. The Asmongas also were active members of the former Homestead and Mifflin Township Historical Society, whose mission was to preserve the past for future generations.

Unfortunately, the days of community adult sandlot baseball leagues largely ended and the later decline of Pittsburgh’s steel industry following the 1970s changed Western Pa.’s physical and economic landscape. Homestead Works closed in 1986. U. S. Steel still remains in the region, though the company was bought out by Japanese corporation Nippon Steel in December 2023. The Asmongas’ sporting legacy, however, continues through the Donald Asmonga Foundation, whose mission “is to promote and acknowledge excellence in Western Pennsylvania athletics … by recognizing student athletes, honoring coaches and teachers, and supporting school and community sports programs.”

About the Author

Craig Britcher is the Assistant Curator of the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum.

Sources: newspapers.com research, https://www.donaldasmongafoundation.org, and greatly appreciated and enlightening conversations with John A. Asmonga’s daughter-in-law Linda Asmonga. Additional thanks to Nancy Asmonga Colleton, Don Asmonga’s daughter; Ron Baraff, Director of Historic Resources & Facilities, Rivers of Steel; Trilby Busch of Steelworks Press, author of “Darkness Visible: A Novel of the Homestead Strike of 1892,” and former Munhall rifle team WPIAL champion; Vincent Ciaramella; Len Martin; and Andy Terrick.

For more on local community baseball history please see “Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh” by Rob Ruck. Visit the Battle of Homestead Foundation’s site to learn more about their extensive efforts to preserve and memorialize the history of the Homestead Steel Strike of 1892.