Franco’s Italian Army, a Pittsburgh Steelers fan group that cheered on rookie running back Franco Harris, recruited an Italian “army of support” to cheer on the Black and Gold in 1972.

At the end of each calendar year, we reflect on the events of the past 12 months, noting the moments that stand out. Sometimes we look back farther into our shared history and recall the decades, acknowledging milestone events. This year the region reflects on one of the most exciting plays in NFL history, the “Immaculate Reception,” which celebrates its 50th Anniversary on December 23, 2022. This commemoration led me to examine the collections the History Center holds related to the fan group known as Franco’s Italian Army and consider what the “Army” tells us about Pittsburgh’s Italian American community. A half a century later, we continue to laud the ways this group chose to cheer on Franco Harris and the Steelers.

Franco’s Italian Army formed to support Pittsburgh Steelers player Franco Harris, a rookie fullback drafted out of Penn State (he was drafted in February while still in school). The fan group became a one-season phenomenon, mostly because the founders each ran businesses full-time. Al Vento, proprietor of Vento’s Pizza, was friendly with members of the Pittsburgh Steelers who frequented his East Liberty shop. He and Tony Stagno, owner of Stagno’s Bakery (also in East Liberty), thought it would take an army to invigorate Steelers fans, who after 39 lackluster seasons needed motivation.

Vento remembered, “Franco Harris and I became acquainted through Sam Davis [Steelers offensive left tackle]. He was a customer of mine. And we all went down to the football games at Pitt Stadium. And then in 1970, when they transferred to the Northside, we went to the games [there]. We’d go every Sunday, and we went as a fun thing. So, when Franco joined the team, and we found out he was half Italian, we sort of was rooting for him at the game.”

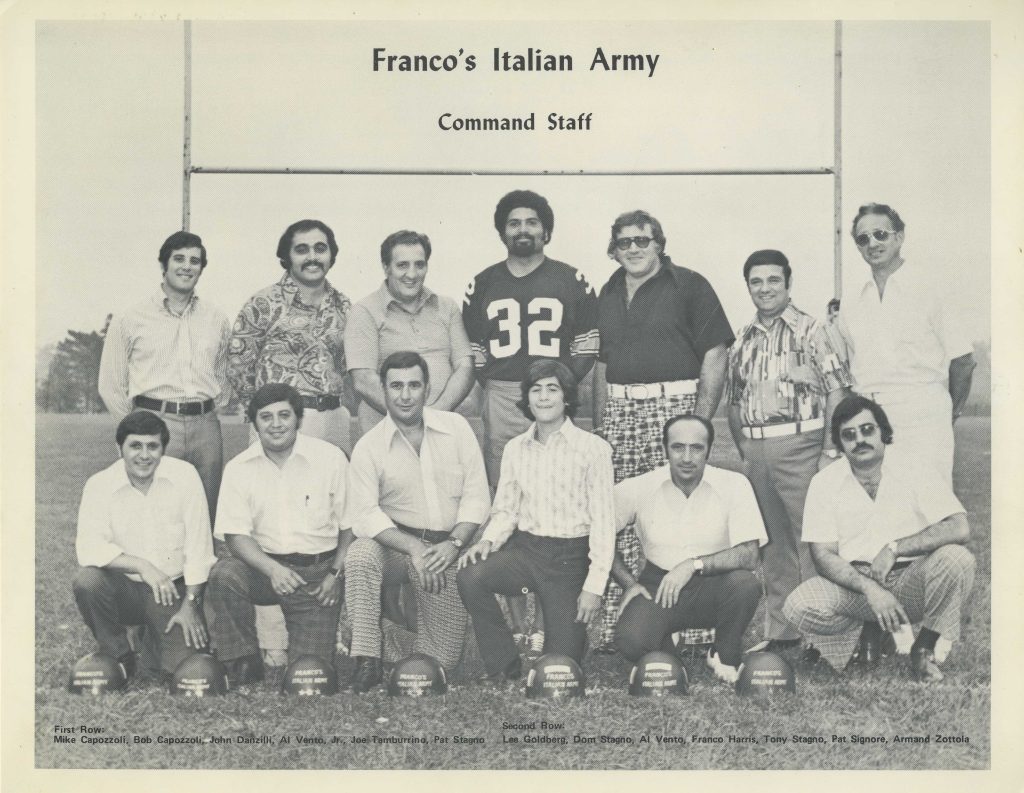

With Franco’s blessing, Vento and Al Vento, Jr., Tony Stagno, Tony Stagno, Jr., Dom Stagno, Pat Stagno, Armand Zottola, Pat “Bronco” Signore, John Danzilli, Mike Capozzoli, Bob Capozzoli, and Joe Tamburrino founded Franco’s Italian Army.

Franco’s Italian Army Command Staff, 1972, Gift of Armand Zottola

The group had season tickets at Three Rivers Stadium, near the broadcast booth, and called attention to themselves with displays of Italian pride and, eventually, military maneuvers. John Danzilli recalled, “Tony Stagno called me one day and said, ‘We are forming this Franco’s Italian Anny, and we need some helmet liners.’ I was in the military, and he said, ‘Can you help us out?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, I think we can figure [something] out…’ Tony had them painted up, and I threw some gold stars on them [to show] who was Generals and Privates and Corporals. And it got to be a fun thing. I happened to have good seats at the stadium, the first row of the second level, so the banner that was made, I used to hang it at every game from my seats. And Tony and Al sat down right below me. And from our second level there, I would hang the banner every time.”

General Helmet from Franco’s Italian Army, 1972, Gift of Al Vento, Sr.

Vento provided hoagies, Stagno brought wine (sometimes smuggled in Italian loaves of bread), and other Italian specialties were shared among the group, creating a Sunday dinner atmosphere in their section of the stadium. Armand Zottola told the story, “One Sunday, Tony Stagno had his wife make ravioli and manicotti. And I mean, we brought down pans. That section we were in, they went wild. Cause soon as it went up, man, especially Myron Cope. He come down, he got some. And his friends up there, up in the booth, they come down, got some ravioli and manicotti and a bottle of wine and some bread, cheese, and pepperoni. Oh, we had a ball! Every Sunday we had a ball.”

Franco’s Italian Army cheering at Three Rivers Stadium, 1972, Gift of Al Vento, Sr.

Quickly, other Steelers fans (including non-Italian Americans) joined in the fun, wearing hats, scarves, and t-shirts emblazoned with the Franco’s Italian Army logo and waving Italian flags. They looked forward to the antics of the Italian Army, who planned their game day spectacles with the permission of the stadium management and members of the media. Danzilli recalled one game when they brought in a tank.

He said, “I had a Jeep and a two-and-a-half-ton truck with a lO5-mm Howitzer behind it, and we were bringing it to the game… We were parading around the inside circle of the stadium and had Italian flags and people inside the two-and a-half-ton. Everything was loaded. We were in the Jeep, Tony Stagno was in the Jeep with me and my wife and everything, and we were driving around the stadium just before the game having a good time.” Another time, the Italian Army “kidnapped” announcer Myron Cope, a two-star General in the Army, from the broadcast booth. The exploits of the troupe were always met with support from the Steelers and their fans, which is exceptional when we consider that the United States was still fighting an unpopular war in Vietnam.

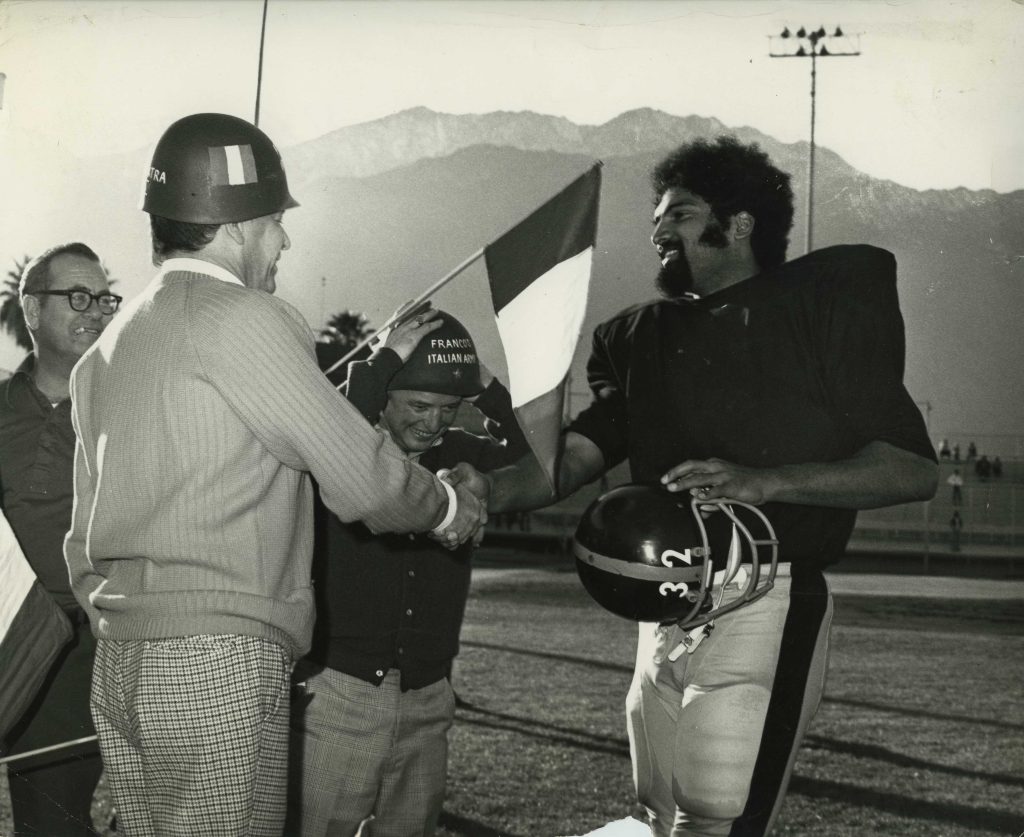

As the media covered Franco’s Italian Army at Steelers games throughout the season and they gained followers, the group ended up appearing on national media through the NFL (you can still watch NFL footage of the Italian Army on YouTube). They also had encounters with celebrities outside the world of sports, with the pinnacle being their meeting with legendary Italian American singer Frank Sinatra. Tipped off by Myron Cope, Vento and Stagno flew to the Steelers practice in San Diego after Sinatra agreed to a meeting. Harris broke away from practice with the permission of Steelers head coach Chuck Noll and the group inducted Sinatra into the Italian Army with a one-star General helmet and a toast featuring the group’s favorite Riunite wine.

As the media covered Franco’s Italian Army at Steelers games throughout the season and they gained followers, the group ended up appearing on national media through the NFL (you can still watch NFL footage of the Italian Army on YouTube). They also had encounters with celebrities outside the world of sports, with the pinnacle being their meeting with legendary Italian American singer Frank Sinatra. Tipped off by Myron Cope, Vento and Stagno flew to the Steelers practice in San Diego after Sinatra agreed to a meeting. Harris broke away from practice with the permission of Steelers head coach Chuck Noll and the group inducted Sinatra into the Italian Army with a one-star General helmet and a toast featuring the group’s favorite Riunite wine.

Franco’s Italian Army inducts Sinatra into their ranks, 1972, Gift of Al Vento, Sr.

When the “Immaculate Reception” occurred, Franco’s Italian Army was in the stands. Zottola remembered, “The ball hit [Oakland Raider Jack] Tatum, Franco was coming down this way, right by us. And somebody says, ‘Franco has the ball.’ I say, ‘No way.’ I saw him stoop and, on the five-yard line, he’s about to be hit. But he got that line, just threw it away. And boy we went wild!” Danzilli recalled the use of the corno during the game, a protection amulet common to Southern Italy.

“Everybody had a little Italian horn, a cornito. Tony [Stagno] had a big one, and it had a humpbacked man inside it. He had this big red thing, and he would point it down at the field.” Vento explained, “It’s supposed to keep the evil spirits away from your body, your family, your possessions.” Vento also explained the malacchio (evil eye), which was used by the Italian Army to disarm Steelers’ opponents. “When you have headaches or feel down and out, well the Italian people, some, in our area, they believe that somebody put the evil spirits on them and wishing them to be ill.”

The early 1970s was an important moment in American history for ethnic and racial pride. After the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and tumultuous events of 1968, the nation entered a period of re-examination of American identity, and citizens who once downplayed or erased their ethnic or racial origins began to embrace those roots. Many went a step further, reclaiming identities by wearing signifiers of their national origin in displays of pride. In the case of Italian Americans, the wearing of the tricolor (red, white, and green) on their body as clothing, the consumption (and sharing) of Italian foods, and the practice of folk customs were ways that they expressed their identity.

These actions may not seem notable today, but there was a time when Americans of Italian heritage could not fully embody the culture of their ancestors in public spaces with the guarantee of safety. Historians interpret Franco’s Italian Army as evidence of the changing American landscape, both in the Italian American communities’ comfort in displaying their pride and the way the mainstream media and American popular culture embraced the fan group.

Always at the center of this movement were the Italian Army’s organizers, who welcomed the energy of crowd and the media, but were thoughtful about what their group represented for the city of Pittsburgh. Vento and Stagno were not interested in commercializing Franco’s Italian Army and kept their focus on having fun, boosting morale, and supporting the Steelers. In his oral history, Vento reflected on the 1970s and the changes occurring in Pittsburgh – industry was on a downturn and urban revitalization disrupted city neighborhoods, displacing residents. Friction existed between the Italian American community and African American community in Pittsburgh’s East End.

The founders of the Italian Army descended from immigrants from Spigno Saturnia, a rural village in central Italy, and were raised in Larimer, Pittsburgh’s former Little Italy. Growing up, they likely experienced marginalization as many Americans of foreign parentage did. By the 1972 season, they had witnessed the dissolution of the Italian business district on Larimer Avenue and the flight of the Italian American community into the Eastern suburbs of Pittsburgh. But, instead of perpetuating cycles of discrimination and exclusion, they formed Franco’s Italian Army with an inclusive mindset and a respect for Harris’s background as an American with Italian and Black ancestry. This attitude pushed back against the tensions of the day, creating an opportunity for Pittsburghers to break away from the challenges they faced on game day and find community in their fandom. Proud of their heritage and their hometown, they put those parts of their identity on view, encouraging others in Western Pennsylvania to be proud of who they were. Fifty years later, we can still find inspiration in their mission.

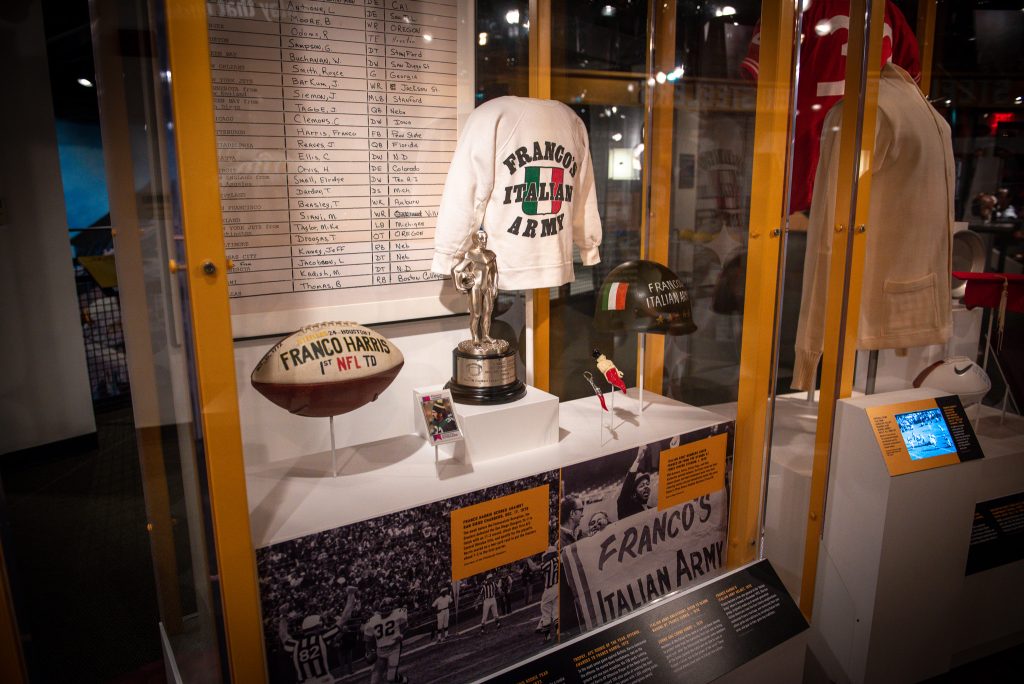

Franco’s Italian Army display in the Super Steelers exhibition.

To see objects from Franco’s Italian Army, the Immaculate Reception, and other artifacts examining the life and career of Harris, visit the Sports Museum’s Super Steelers exhibition.

Bibliography

Oral History with Al Vento 2002.0067

Oral History with John Danzilli 2002.0068

Oral History with Armand Zottola 2002.0069