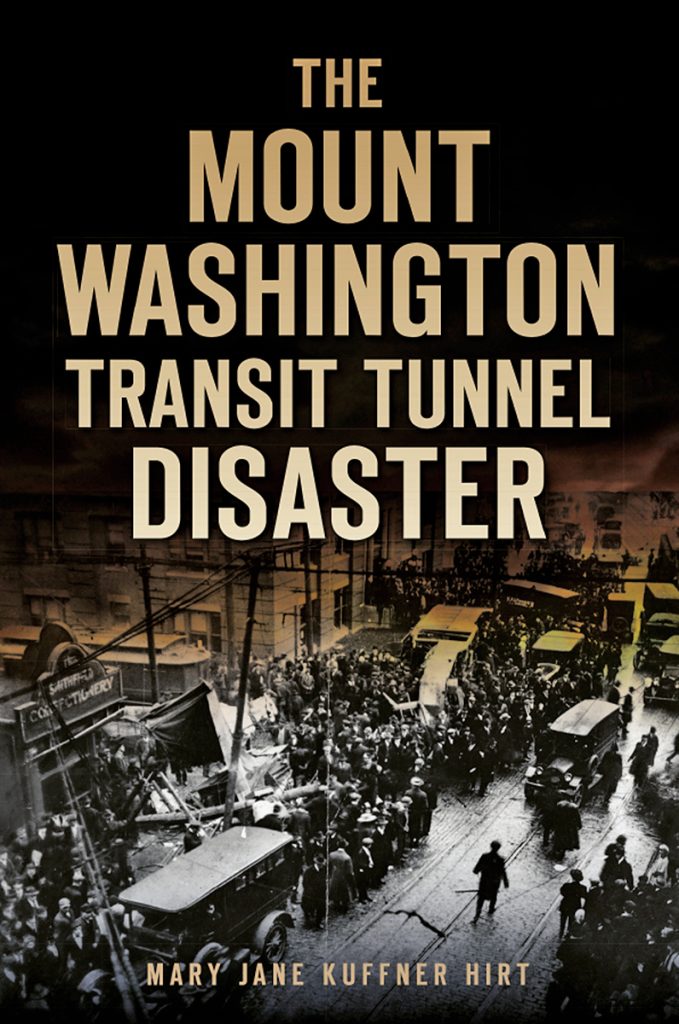

The Mount Washington Transit Tunnel Disaster

By Mary Jane Kuffner Hirt

The History Press, 2021

192 pages, 60 photos and maps

Paperback, $21.99

Reviewed by Mark Holan, Pittsburgh native and editorial director of the American Road and Transportation Builders Association in Washington, DC.

Two dozen people were killed December 24, 1917, when a Pittsburgh Railways streetcar crashed near the south end of the Mount Washington Transit Tunnel near the Smithfield Street Bridge. Scores more were injured in what remains the city’s greatest transit tragedy.

Author Mary Jane Kuffner Hirt of Harmar, PA, a local government consultant and genealogist, has a family connection to the event: her grandfather’s cousin was among the fatalities. The book “evolved like a set of reverse nesting dolls,” she writes, from her search for this ancestor. It expanded to include the other passengers, bystanders, rescuers, streetcar company employees and officials, and government and community leaders drawn into the larger narrative.

Knowing the horrific outcome, readers will probably feel the foreboding of that cold and rainy Christmas Eve afternoon as 114 workers, last-minute shoppers, and holiday visitors packed inbound car #4236 along the Knoxville line. The car entered the tunnel at South Hills Junction and the trolley pole soon lost contact with the wire. The motorman from the following Charleroi car stopped and reset the lead car’s pole. When the lights and power returned, the apparently impatient motorman inside #4236 opened the controller to full speed and the car careened down the tunnel’s steep incline toward the city.

The car jumped the outbound tracks, crashed through a fire hydrant and two utility poles, slid 100 feet across the cobblestones, and slammed into an iron fence in front of the Pennsylvania & Lake Erie Railroad terminal annex. Kuffner Hirt has calculated the explosive impact as more than a dozen sticks of dynamite, enough to blow up several tons of rock.

The fatalities included 17 women and girls, and seven men and boys. One woman at the corner was crushed so badly, she was never identified. Their ages ranged from 10 to 57. Kuffner Hirt not only provides the victims’ names, addresses, and other biographical details, but also identifies all the survivors and rescuers, the experiences of many told in their own words from newspaper reports and criminal and civil legal proceedings, which stretched on for years.

Kuffner Hirt also provides important context about life in Pittsburgh eight months after the United States entered World War I and weeks before the outbreak of the 1918 influenza pandemic. She includes details about the construction of the Mount Washington Tunnel, opened in 1904, the St. Louis-built streetcar model involved in the crash, and the 1918 bankruptcy of Pittsburgh Railways. The book contains more than 60 images, including the crash scene, the newspaper headline “Death Car Motorman Guilty,” and the Western Penitentiary identification card of that employee, who served a 15-month manslaughter sentence.

The still-operating transit tunnel will make this story accessible to modern Pittsburgh readers, even if other aspects of the early 20th-century city are difficult to recognize. It is not a happy story, but it deserves this detailed remembrance.