It was an ash dump, a firehall, a market for butchers, a place to relax for Chinese residents, and home to an alligator that roamed the city at night. Most oddly, it was in the middle of a street. It was Pittsburgh’s first park—erased for the past century, though you can still easily find its location.

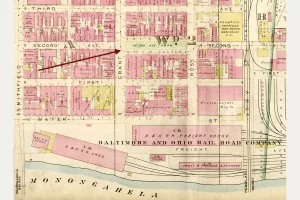

The park sat in the midst of Second Avenue between Grant and Ross Streets—where the Boulevard of the Allies ramp now lands in downtown. A deed of 1811 conveyed from industrialist James O’Hara to the city “certain portions of lots in Second Street [its original name]1 for the accommodation of a market house,” and so the Scotch Hill Market House was built down the middle of the block.2

Scotch Hill was the southern base of the much-larger Grant’s Hill, named, like Grant Street, for Major General James Grant. In 1758, Grant led his Scotch Highlanders Regiment down from the bluff, intent on capturing Fort Duquesne at the Point. His mission failed, but the Scotch Hill name honored the troops who fell there.3

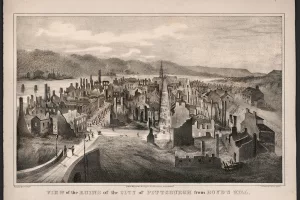

On April 10, 1845, the Great Fire burned some 1,200 buildings downtown, including Scotch Hill Market. Amazingly only two deaths were reported from the massive blaze—both on Second Street adjacent to the market house. One, Samuel Kingston, a friend of Stephen Foster, was trying to rescue his piano.4 The other, Mrs. Malone, was last seen at the market house; her bones were found in a cellar two weeks later, as were Kingston’s a month after that.

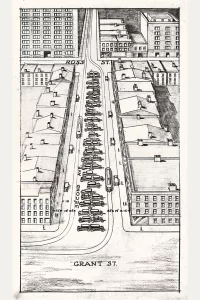

The market was rebuilt, but by 1858, an ordinance stated, “the public market house on Second Street is of no benefit to the city” and that the Ross estate, which now owned the lifeless strip, agreed it “may be used as a public square.”5 In the century since the French were driven from the forks of the Ohio, the city had not had a park.6 Small as it was, the new park was a major step for the city, which would not have another municipal park until Schenley Park was created in 1889; downtown parks at Mellon Square, Market Square, and Point State Park were still a century in the future.

In 1873, a box was delivered to Second Avenue Park.7 Inside was an alligator, a present from Daniel Ferry of Louisiana.8 A news story recalled that the gator lived in the park fountain, though “it had a habit of leaving its native habitat after dark and spending the nights in slumber on the door steps of adjacent dwellings, much to the terror of peaceful female domestics who encountered it in the early mornings when they went out to sweep the pavements.”9 One night the gator left and was never seen again, likely slipping into the Monongahela River.

As the park and housing prices around it declined, more than 300 Chinese residents moved there from the Hill District and created a bustling business district.10 Local historian George Swetnam later wrote that tile-roofed buildings lined both sides of the little park, “where the people of Chinatown gathered in the evenings.”11

In 1913, Monongahela Boulevard was proposed to connect the city with Oakland along the bluff but needed a way to descend from Duquesne University into downtown.12 The park was the perfect site to land the four-lane road (by 1919, officially named Boulevard of the Allies).13 However, the wide block was not quite wide enough, so in 1921, almost all Chinese residents and businesses were forced to move to make way for demolition. The concrete ramp was connected eastward to a new iron viaduct directly above Second Avenue.14

As for Scotch Hill Farmers Market and Second Avenue Park, they were quickly forgotten in the automobile-era frenzy.15

Special thanks to Charles Succop, City Archivist, for his assistance with city documents, and Jennifer Sopko for the streetcar map that started it all.

Read the full story of the park in the Winter 2022-23 issue of “Western Pennsylvania History” magazine.

About the Author

Brian Butko has published books on local and roadside businesses and is writing a haunted historical mystery inspired by his hometown quarry. He is editor of Western Pennsylvania History magazine.