“For I was nineteen when I came to America and then I at once became an American Workman.” -John Kane

Beechwood Boulevard (now Greenfield Bridge) construction crew with John Kane pictured in second row far left, 1923. Courtesy of The Leon A. Arkus Collection of John Kane, 1931-1987, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh Archives & Special Collections

By the mid-19th century, the broad swath of coal that cuts through this region provided fuel for burgeoning industries such as iron, glass, and eventually, steel. It created jobs as well, in the mines and coke works found throughout the area. Many immigrants made Western Pennsylvania their destination of choice, seeking opportunity and work. Driven by dreams of a better life, they also fled poverty, hatred, and war.

Often, migrants to the region found hard work that paid as little as 12 cents an hour and demanded that a body endure 10-hour days, brutal conditions, and little security. John Kane and his family members were among those that labored six to seven days a week in dangerous conditions. Though he relished the physical challenges of the work he found, first in steel, then in the coal mines and coke works, Kane moved often. He went from place to place and job to job searching for something better–more money and less arduous conditions.

Puddling furnaces at Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation, by Frederick T. Gretton, 1885. Gift of Mrs. Wilbur Galbraith

Many industrial laborers at the turn of the century, were highly mobile. As mechanization eliminated skilled high-wage jobs, unskilled workers were left with low paying, often seasonal, work. Laborers such as Kane often hopped aboard a passing freight train for a free ride as they searched for their next opportunity. Kane went as far south as Alabama and west to Tennessee looking for work. His life story, told to journalist Marie McSwigan and published in his autobiography, allows us to trace his work journey in the United States and document the industries that shaped his life and art.

Kane’s stepfather, brother, and cousin migrated here in 1879, a year before he left Scotland. Those family members found work at the Edgar Thomson Works in Braddock, Pa. Though he landed there first, Kane only lasted a few months before returning to the work he knew and preferred. Kane had experience in Scotland working in the shale mines that ringed his hometown of West Calder. Declaring, “There was always a job for a Scotch miner,” Kane found work in the coal mines of Connellsville, in Fayette County. Like thousands of others, he proved willing to spend the day underground in the mines and also to do the brutally hot, back-breaking labor of feeding the coke ovens in that area. Miners such as Kane faced immense danger—roofs collapsed, mines flooded, toxic gases killed or caused explosions. More than 20,000 miners died on the job between 1900 and 1910 in the U.S., many of them immigrants. Kane experienced the danger firsthand, surviving a fire that put 300 miners at risk. He later recalled, “at a time like that death walks too close for anything but quiet thankfulness of heart.”

Cooling, Drawing, and Loading Coke, H.C. Frick Coal Co., 1898. More than 30,000 coke ovens in the Connellsville region of southwestern Pa., many owned by H.C. Frick, transformed millions of tons of coal into coke for the iron and steel industry. From Report of the Bureau of Mines of the Department of Internal Affairs, 1898

In his constant search for better pay, Kane returned to Pittsburgh and found a job with the John Callahan Company of Pittsburgh as a street paver. He recalled the exhausting nature of the work in the beginning, stooped over all day, lifting, “hundreds upon hundreds” of 30-to-40-pound stones. But he developed a knack for recognizing and choosing just the right stone to fit each spot, saving himself from what he called, “the try method.” Kane eventually earned five dollars a day paving the streets of downtown, Carson Street on the South Side, and Fifth Avenue in McKeesport. Carson Street later became the focus of a painting, Industry’s Increase, that Kane exhibited in the Carnegie International.

Road paving on Wilkins Avenue, Pittsburgh, c. 1912. Courtesy of University of Pittsburgh, Archives Service Center

Kane, who never lost his interest in sketching and drawing, once remarked, “When my back wasn’t hunched over blockstone, at lunch, or some other time, I would get out my pencil and make drawings.” Street paving furthered his work as an artist, developing his visual talent and teaching him to compose the precise patterns that formed his paintings. But an injury ended Kane’s ability to do this type of work.

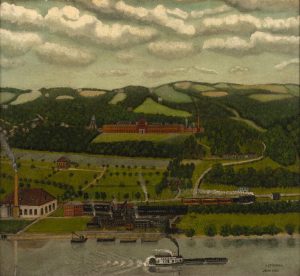

Aspinwall, by John Kane, oil on wood panel, no date. Kane found landscape subjects as he moved from worksite to worksite. This section of the Allegheny River, discovered while on a job many years before he could paint it, became a favorite. Courtesy of Arkell Museum at Canajoharie, gift of Bartlett Arkell, 1941. © Estate of John Kane, Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York.

The railroad proved central to John Kane’s life–he rode the rails in search of work and labored in different sectors of the industry. But it also altered the course of his life. John Kane lost his lower leg in 1891, clipped by a train as he took a shortcut across the railroad tracks late one night. He suffered from infections and the pain caused by ill-fitting prosthetics for the next 40 years. Other members of his family suffered similarly – his brother Patrick suffered an arm injury and his brother Tom and half-brother Simon were killed in railroad accidents. After his injury Kane recalled, “It was not the first nor the last time my mother’s heart ached from railroad disasters in our family.”

From the trauma however came an opportunity that changed Kane’s life. After recovering, Kane secured a night watchman’s job with the B&O Railroad. Eventually he took a position at Pressed Steel Car Co. in McKees Rocks painting boxcars. There he learned to use lead paint and mix colors. At lunchtime the foreman allowed him to paint scenes on the cars before they were repainted. This advanced his abilities, “I felt like a king. I had just learned the use of color in my art work.”

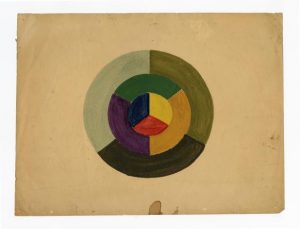

Untitled, (Color Wheel), by John Kane, tempera on paper, no date. Kane bragged that he could mix any color from the three primaries plus black and white. The theory worked for his house painting and fine arts practices. Courtesy of American Folk Art Museum, New York, gift of Michael Roland, Sean Roland, Timothy Roland, and Jacqueline C. Elder in loving memory of Margaret Kane Corbett, 2006.10.9. © Estate of John Kane, Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York.

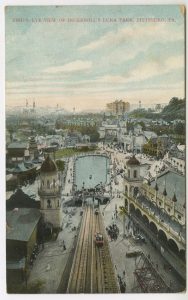

Unable to work jobs requiring heavy physical labor, Kane increasingly found work on construction projects, as a carpenter and a painter. He painted the buildings and attractions at the short-lived 16-acre Ingersoll Luna Park in North Oakland. Opening in 1905, it inspired dozens of other Luna Parks around the world. Kane recalled his work at Luna Park, “I painted the shoot the chutes, the roller coaster, the crazy house and I don’t know what all besides. The top of the merry-go-round…. The whole park was done in white and gold and was as pretty a sight as fresh paint could make it.” Kane also worked on other buildings throughout the region, painting homes, offices, and businesses.

Bird’s-Eye View of Ingersoll’s Luna Park, Pittsburg, PA, c. 1905. Postcard collection, Detre Library & Archives.

The best jobs, like the two years he spent painting the offices at the National Tube Works plant in McKeesport, paid a good wage and gave him the freedom to make creative choices. Working indoors, coordinating with clients, having a say in the colors he mixed and the decoration he applied, proved fulfilling. Kane continued to work as a house painter until opportunities ceased during the Great Depression. He painted his last house in 1929, then entered what he described as, “a new period in my life.” During the last five years of his life, Kane pursued his art, not just at night, on Sundays, or on rainy days, but all the time.

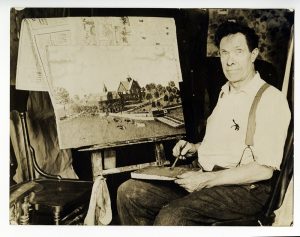

John Kane at easel working on Steel Farm II, 1927-30. Courtesy of The Leon A. Arkus Collection of John Kane, 1931-1987, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh Archives & Special Collections

Kane’s work came to inform his art. From street paving he learned precision, how to compose a drawing or landscape. While painting railroad cars, amusement park buildings, hotels, and homes, he studied color – mixing and layering paint to achieve the desired effect. Whether a member of a work crew or a solitary laborer, Kane took pride in his mastery of demanding tasks performed under difficult conditions and in his contributions to building this city.