We commemorate June 6, 1944, as “D-Day,” the start of the Normandy invasion and a crucial turning point during World War II. But at the time, nothing about that campaign was a foregone conclusion. For U.S. and Allied military leaders, debates about the scheduling and logistical challenges of a European invasion shaped decisions years in advance of the actual landings, which some originally hoped would occur in 1943. The shortage of key equipment contributed to delays that pushed the invasion back by more than a year. Filling that gap impacted the lives of thousands of Western Pennsylvania workers, even if they did not initially realize what it was that they were creating.

Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder

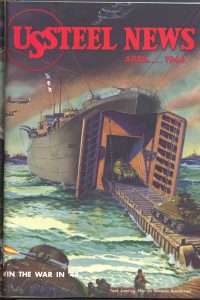

The missing piece of key equipment in question was a ship, a large transport vessel known as an “LST,” or “Landing Ship, Tank.” The length of nearly a football field, with high, wide decks and a flat keel (or bottom), the LST was no beauty. But it was an essential workhorse that carried the men, vehicles, supplies, and equipment needed to wage a ground invasion. It represented an important strategic collaboration between two nations and a logistical need without which many believed the invasion of Normandy was impossible.

As the United Kingdom’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill reportedly once wrote in a letter to U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall, “the destinies of two great empires . . . seemed to be tied up in some god-damned things called LSTs.”

Churchill was among the first to recognize the need for a transport vessel that could land men and equipment directly onto the beaches of a battle theater. His awareness of disasters such as the ill-fated invasion of Gallipoli in World War I and Dunkirk early in World War II convinced him of the usefulness of a new kind of landing craft. But war-besieged Britain had neither the money nor resources to build such a fleet; after some early attempts to modify existing craft, they turned to the United States to create a more workable solution.

Dravo Leads the “Cornfield Navy”

The need for LSTs was so urgent that once a design was finalized, production demands far outstripped the capacity of the nation’s main ship-building centers to handle the load. So, a set of five shipyards along America’s inland waterways—four along the Ohio River and one on the Illinois River—spearheaded the production of more than 600 of the massive ships. Dubbed the “cornfield navy,” these yards, mainly bridge and machine builders with expertise constructing barges and steamboats, played an outsized role in ensuring that the men, vehicles, and equipment needed for D-Day and other battles in the European and Pacific theaters made it to their destination. The same vessels also proved crucial for the medical evacuation of wounded soldiers.

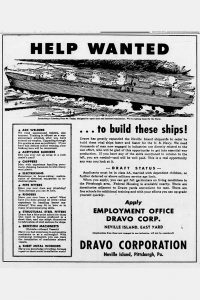

Pittsburgh’s Dravo Corporation served as lead yard for the effort, pioneering new techniques for assembling ships and barges in an accelerated timeframe at a reduced cost. Taking advantage of being in one of the nation’s leading steel production centers, they gathered prefabricated sections of LSTs made at five area plants and brought them together to finish at their Neville Island yard. As one vessel launched into the Ohio River, more would be in production behind it. The sections were welded together rather than riveted, a job that eventually opened to thousands of women as well as men, creating all-women welding crews at Dravo and the American Bridge Company, a U. S. Steel Subsidiary in Ambridge, Pa., the other Western Pa. yard participating in the effort. *

Dravo had already launched a new type of subchaser (PC-490) for the U. S. Navy in October 1941, the first combat vessel built in Pittsburgh since the War of 1812. Such efforts earned Dravo the nation’s very first All-Navy “E” Award for production in March 1942. Their status as lead yard for the LST contract meant that they trained others how to use their techniques.

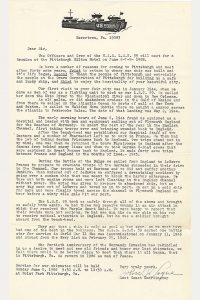

The first inland-made LST, given the unglamorous name “LST-1,” slid down Dravo’s greased launch ways into the Ohio River during lunch hour on Labor Day, Sept. 7, 1942. Thousands of people gathered along the banks of the Ohio River near Emsworth, Pa., to watch the spectacle. (They also climbed trees and gathered on the roofs of nearby buildings.) The crowd whistled and cheered as the massive ship slid into the river, causing a wake so large that it sent people scurrying up the banks to avoid getting wet. At that moment, it was the largest warship ever launched on the nation’s inland waterways.

LSTs at Normandy and Beyond

Over the next three years, a similar sight played out as more than 250 LSTs launched from Dravo and American Bridge, making their way toward the Mississippi River and then points overseas. According to existing records, at least 53 Pennsylvania-made LSTs participated in the D-Day campaign in 1944. They included LST-1, whose crews earned four battle stars, among them for landings at Salerno, Anzio, and Normandy. In truth, there were never enough LSTs to meet demand. At Normandy, being too valuable to risk in the chaos of the opening invasion, they were held further out at sea, then landed in the days after the primary assault, offloading the tanks, jeeps, and other equipment necessary for the push inland. Multiple Pittsburgh-made LSTs also participated under the flag of the British Royal Navy.

Between 1941 and 1945, Davo’s workforce increased from 1,500 people to 25,000. Add to that the thousands who also worked at American Bridge, and tens of thousands of people across the region participated in creating a resource deemed indispensable for the success of the D-Day campaign as well as other marine landings during the duration of World War II. While the ungainly LST may never have gotten the attention and adulation afforded to more glamorous vehicles such as the bombers, fighter planes, jeeps, and tanks that rolled off assembly lines elsewhere, World War II wouldn’t have been won without them.

_____

*The other yards included the Missouri Valley Bridge & Iron Company, Evansville, IN, the Jeffersonville Boat & Machine Company, Jeffersonville, IN, both on the Ohio River, and the Chicago Bridge & Iron Company’s shipyard on the Illinois River in Seneca, IL. The humorous term “cornfield navy” overlooked the nation’s once-rich but forgotten heritage of steamboat-building along the inland waterways.

For further reading

“Biggest Warship Ever Built Inland Launched by Dravo,” The Pittsburgh Press, September 7, 1942

“Dravo Launches New Tank Carrier, Sub Chaser,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, September 7, 1942

Commander Kendall King, “LSTs: Marvelous at Fifty,” Naval History Magazine, Vol 6: No 4 (December 1992). Available online

“Tank Landing Ship Launched by Dravo,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 8, 1942

Andre B. Sobocinski, “The Workhorse of Normandy: Remembering the Roles of LSTs in Medical Evacuation,” The Sextant, May 21, 2019. Available online

Craig L. Symonds, “Normandy’s Crucial Component,” Naval History Magazine, Vol 28: No 3 (June 2024). Available online

Website of the United States LST Association. This site includes many photographs and other information regarding the history of these vessels, which also saw service in the Korean and Vietnam Wars.

About the Author

Leslie Przybylek is a senior curator at the Heinz History Center.