Looking back to the 1930s and the start of a decades-long career in industrial design, Ralph Kruck recalled a profession mired in tradition and resistant to innovation.

Amid the first wave of professional industrial designers, Kruck found that those who “suggested deviating from the styles in his grandmother’s parlor were looked upon as a revolutionary, a radical and a crackpot” by tradition-bound engineers and salesmen.1 Aiming to make products more functional and efficient, industrial designers would become fixtures at leading firms and transform everything from vacuum cleaners to railroad locomotives.

After stints as a musician and an apprentice at Tiffany, Kruck enrolled at Carnegie Institute of Technology (CIT, now Carnegie Mellon University) in the mid-1920s to study design. Westinghouse was urging the school to create a night course for company employees to learn “the fine art of design as applied to electrical machinery.”2 Kruck developed a friendship with Professor Donald Dohner, who would soon lead Westinghouse’s design program and launch the world’s first dedicated industrial design program at CIT. After graduation, Kruck secured a position at Westinghouse, working in the “mechanization processing” division based in Springfield, MA.3

Kruck’s job required drafting new product designs, creating models, and persuading Westinghouse executives to adopt his plans. As the Great Depression wore on, Kruck found that resistance to new design ideas softened as companies sought to revive lagging sales. His work with Westinghouse expanded into new areas, including designs for an X-ray machine and the introduction of a new color scheme for the interior of the University of Pennsylvania hospital in Philadelphia. Kruck’s palette of blue, green, and dusty rose replaced the whites and grays traditionally used in hospitals, which reflected new research into the therapeutic effect of colors on patients. Though he received accolades and won awards from Westinghouse for this work, Kruck chafed at his lack of autonomy. He would later say that the “paternalistic attitude of large corporations makes you soft. You don’t want to take responsibility, and you are afraid of losing your job. They have the money, and you can use it, but what you produce is theirs.”4 He resigned and launched his own firm on Long Island.

In 1946, Kruck was featured in a Popular Mechanics article about the future of industrial design. Envisioning the “kitchen of tomorrow,” Kruck predicted that appliances would be integrated to increase efficiency. “We know that a kitchen designed as an entity will have the same proportionate increase in efficiency that a modern automobile has over a casual assemblage of parts and wheels.”5

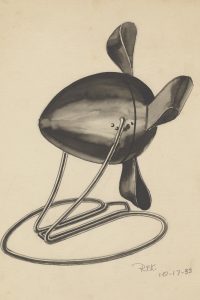

Kruck’s work at Westinghouse is documented by the collection of his drawings held by the Detre Library & Archives. His work depicts a range of domestic products, including radios, fans, and refrigerators. Looking at Kruck’s illustrations today, nearly a century after their creation, it can be difficult to realize how groundbreaking they must have been. In fact, their very ordinariness may be a result of how influential and commonplace designs like these have become.

To learn more about the contents of the History Center’s Ralph E. Kruck Drawings, please view the collection’s finding aid.