There are certain moments in sports that define a team, an era, or an individual. The Immaculate Reception is one of those defining moments – separating the same old Steelers from the Super Bowl Steelers. In the minds of many fans, the Immaculate Reception has become associated with the Steelers’ first Super Bowl victory. In fact, it would be two years before the team won its first championship, but this play changed the team’s fortunes and identity. In a matter of seconds, the team went from lovable losers to probable winners, launching an era when the Steelers and their city became known nationwide as champions.

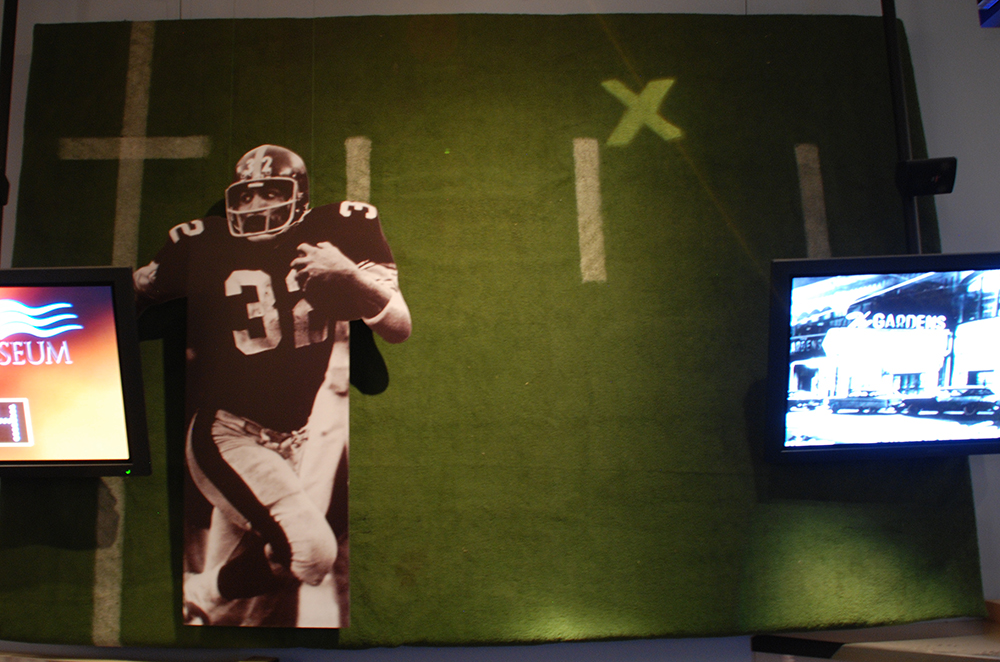

The play itself had all the dramatic elements needed for a “legendary” moment: Less than 30 seconds on the clock, the Steelers behind 7 to 6, facing fourth and 10 with no timeouts, a packed house of 50,000-plus at Three Rivers Stadium, an AFC divisional playoff game on the line, and a rookie running back who inadvertently became central to the action. Even 45 years later, we can all remember how this most memorable (and most controversial) play rolled out. Quarterback Terry Bradshaw scrambled to avoid Raiders linemen Tony Cline and Horace Jones, then fired a pass toward Frenchy Fuqua. The pass bounced off the Raiders’ Jack Tatum and was scooped out of the air just before it hit the ground by Franco Harris. He evaded Raiders linebacker Gerald Irons and stiff-armed Jimmy Warren en route to the end zone. As Harris scored, bedlam ensued; Steelers players celebrated and hundreds of fans rushed onto the field.

It took the officials almost 15 minutes to sort out what had happened, clear the field, and after Roy Gerela’s extra point, award the Steelers their first-ever playoff victory. That night, Sharon Levosky called Myron Cope before his 11 p.m. broadcast and suggested the name her friend Michael Ord had used to describe the play: “The Immaculate Reception.” When Cope used the term on air, associating a religious miracle with a football moment, the immortalization of the Immaculate Reception began. The legend of that moment has only grown as time has passed.

Perhaps that mythology has as much to do with what came after the moment as it does with the event itself. Before Harris charged into the end zone, the Steelers had struggled for more than 40 seasons, hampered by the often-divided attention of their owner Art Rooney, limited financial resources, and lack of a home field. All that began to change in the 1970s as Dan Rooney became the driving force of a team led by Coach Chuck Noll. Noll built the nucleus with drafts of Joe Greene, Terry Bradshaw, Mel Blount, Jack Ham, and Harris. In 1974 Art Rooney Jr., Bill Nunn, and the scouting team put together what has been considered the best class ever, drafting four future Hall of Famers.

By agreeing to join the American Football Conference in 1970, the team received a substantial infusion of cash. That same year, the team moved into Three Rivers Stadium, a venue far superior to Forbes Field and Pitt Stadium. “Monday Night Football,” which began in 1970, offered a national audience for the Steelers as they began their ascent in the 1970s, just as the downturn in the steel industry created a diaspora of job seekers from the city. The two audiences combined to create Steelers nation, reveling in the success of their sports teams even as the bottom dropped out of the regional economy. A new identity as the City of Champions was forged in the 1970s, with the Immaculate Reception serving as a foundation and the four Super Bowl victories as the cornerstone of that identity.

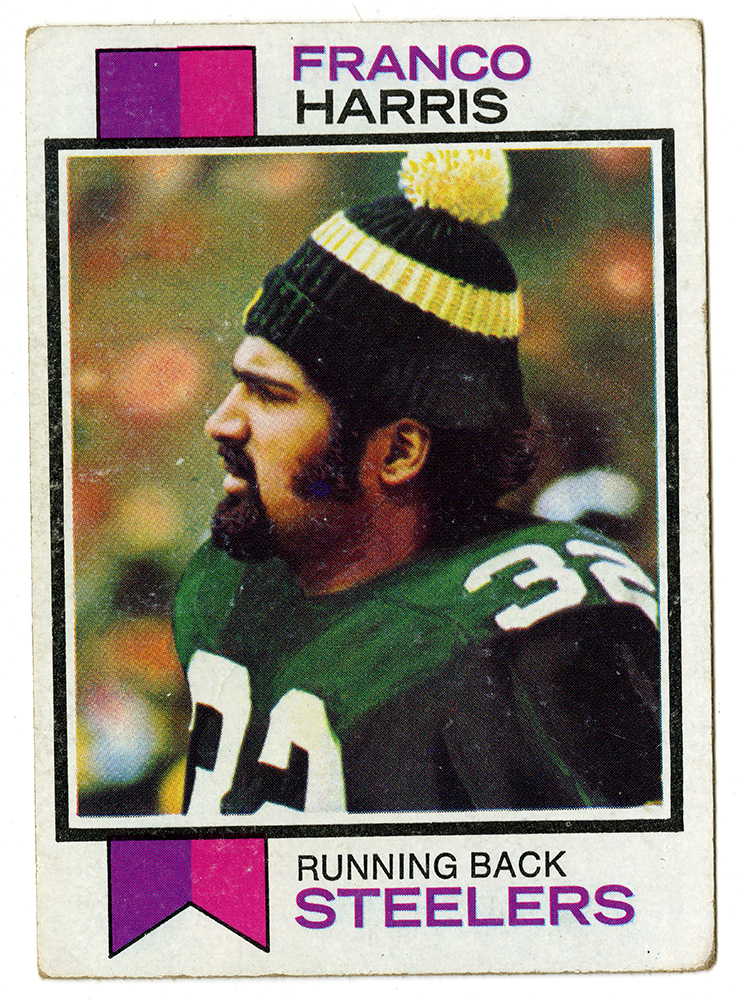

Courtesy of Franco Harris.

Anne Madarasz is the Director of the Curatorial Division, Chief Historian, & Director of the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum.