Confronting shelter-in-place rules and economic uncertainty at a time when visiting the grocery store is a scary proposition, Americans are turning again to home gardens. As seeds and garden supplies fly off virtual store shelves, we recall the “Victory Gardens” of World War I and World War II. How do the experiences of those events compare with our current situation?

Plants as Propaganda

Today, Facebook groups, websites, and social media networks share information and encourage a grassroots return to home gardening. The gardens of World War I and World War II were official initiatives of the U. S. government: propaganda transformed into civic action.

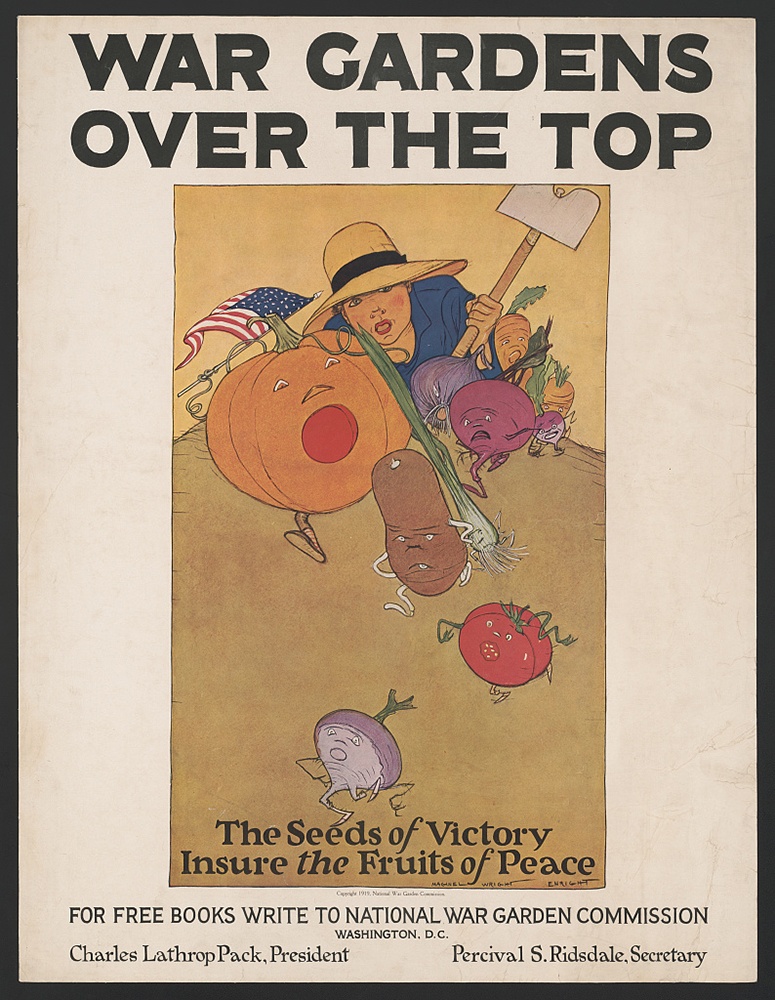

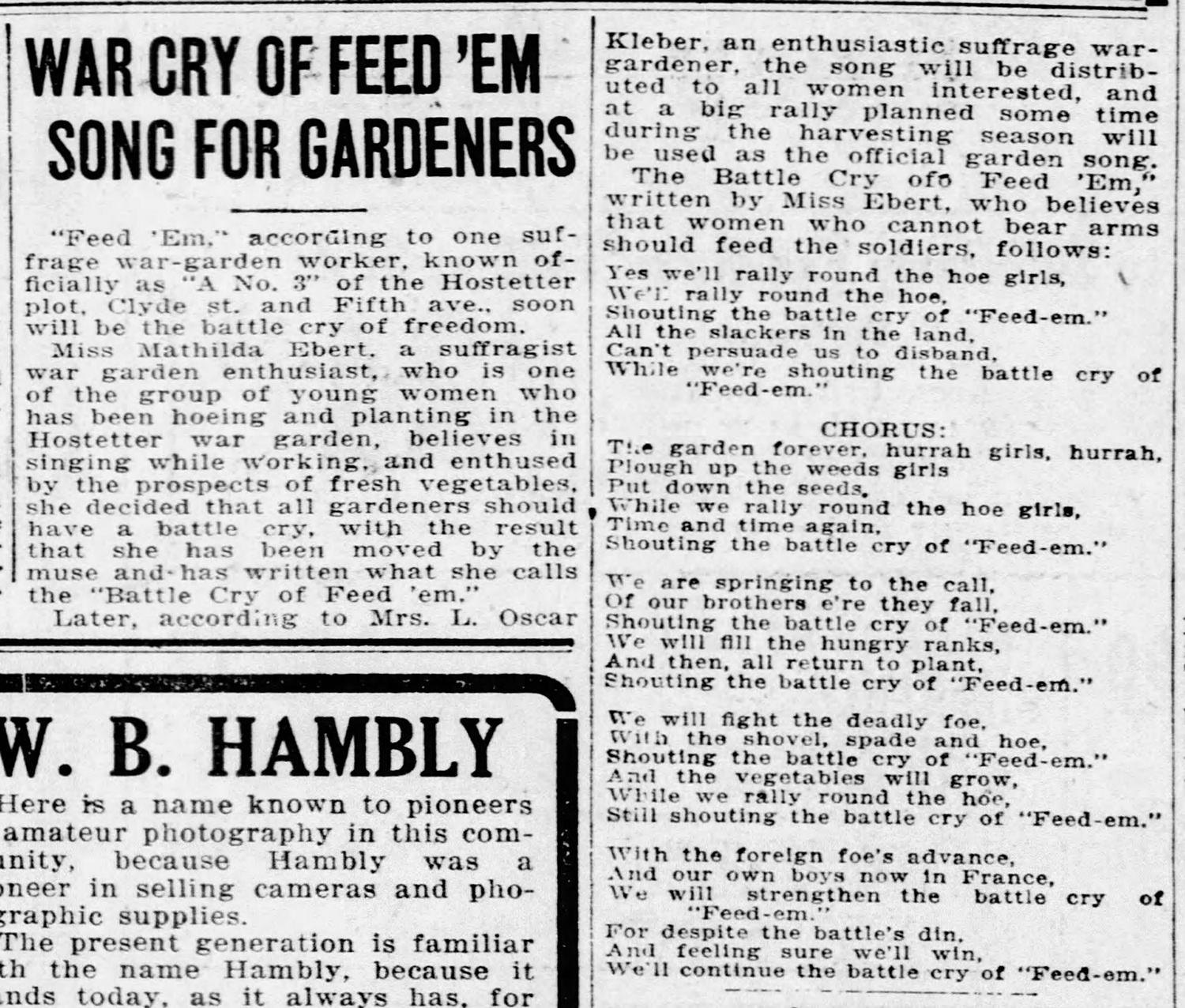

The experience during World War I was brief but crucial. Prompted by food shortages in Britain and Europe (fighting since 1914), the American “war garden” movement emerged when the U.S. National War Garden Commission organized a month before America entered the conflict in April 1917. Rallying citizens to cultivate all available space, even offering free seeds and plans, organizers played off Progressive era interests, when plants served as propaganda in other social movements. For example, women’s suffragists planted gardens of yellow and white flowers to symbolize their cause.

War gardens bolstered food supplies and highlighted Progressive concerns about preserving the usefulness of urban land. While the War Garden Commission’s slogan “sow the seeds of victory” is well-remembered today, less so was its other refrain: “put the slacker land to work.” The idea found expression in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in July 1917, when a writer lamented the “conspicuous examples” of fertile land lost to manufacturing, including along the river bottoms near McKees Rocks and most egregiously, the “rich loamy soil” of Neville Island, once an agricultural powerhouse. Even Henry Clay Frick offered up two plots of land for war gardens

Rise of the Victory Garden

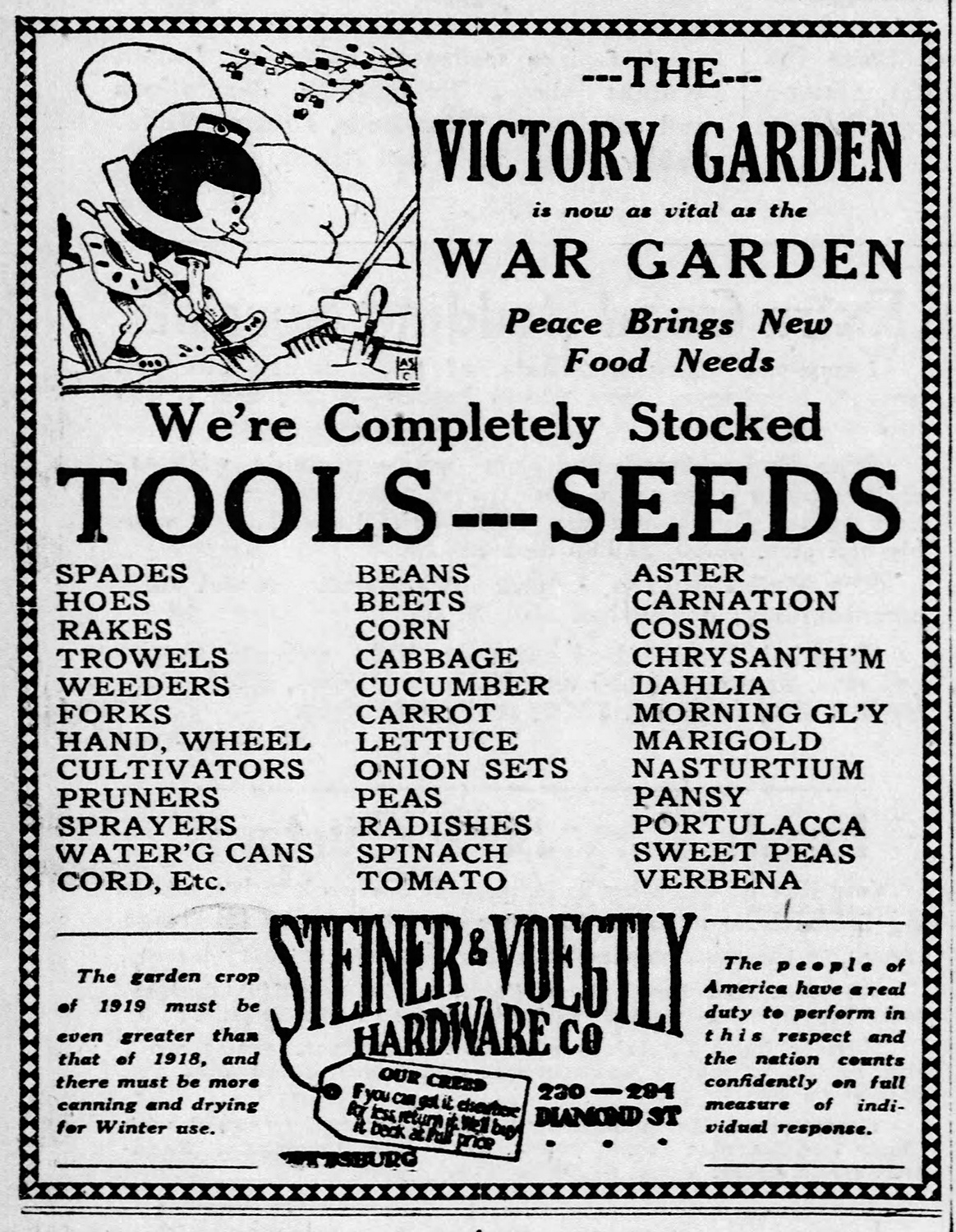

These plots became “victory gardens” after World War I ended in 1918. With Europe devastated, Americans were urged to continue their efforts in 1919 to help ensure that victory would yield stability and peace overseas. While home gardening lost momentum in the 1920s, it returned with new urgency in the 1930s, after the Great Depression threw millions out of work and left many desperate for food. Some scholars argue that the success of victory gardens during World War II was built on experience gained during this period.

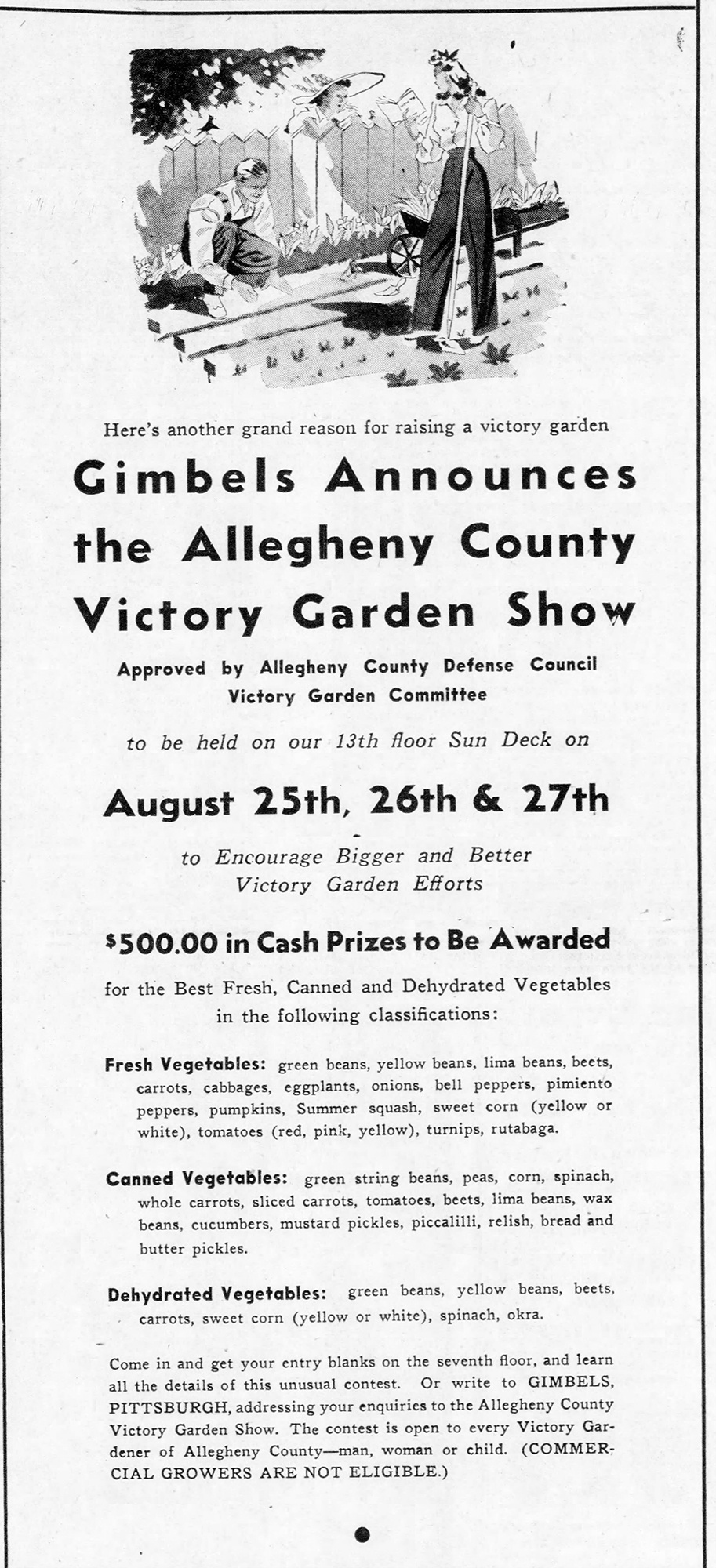

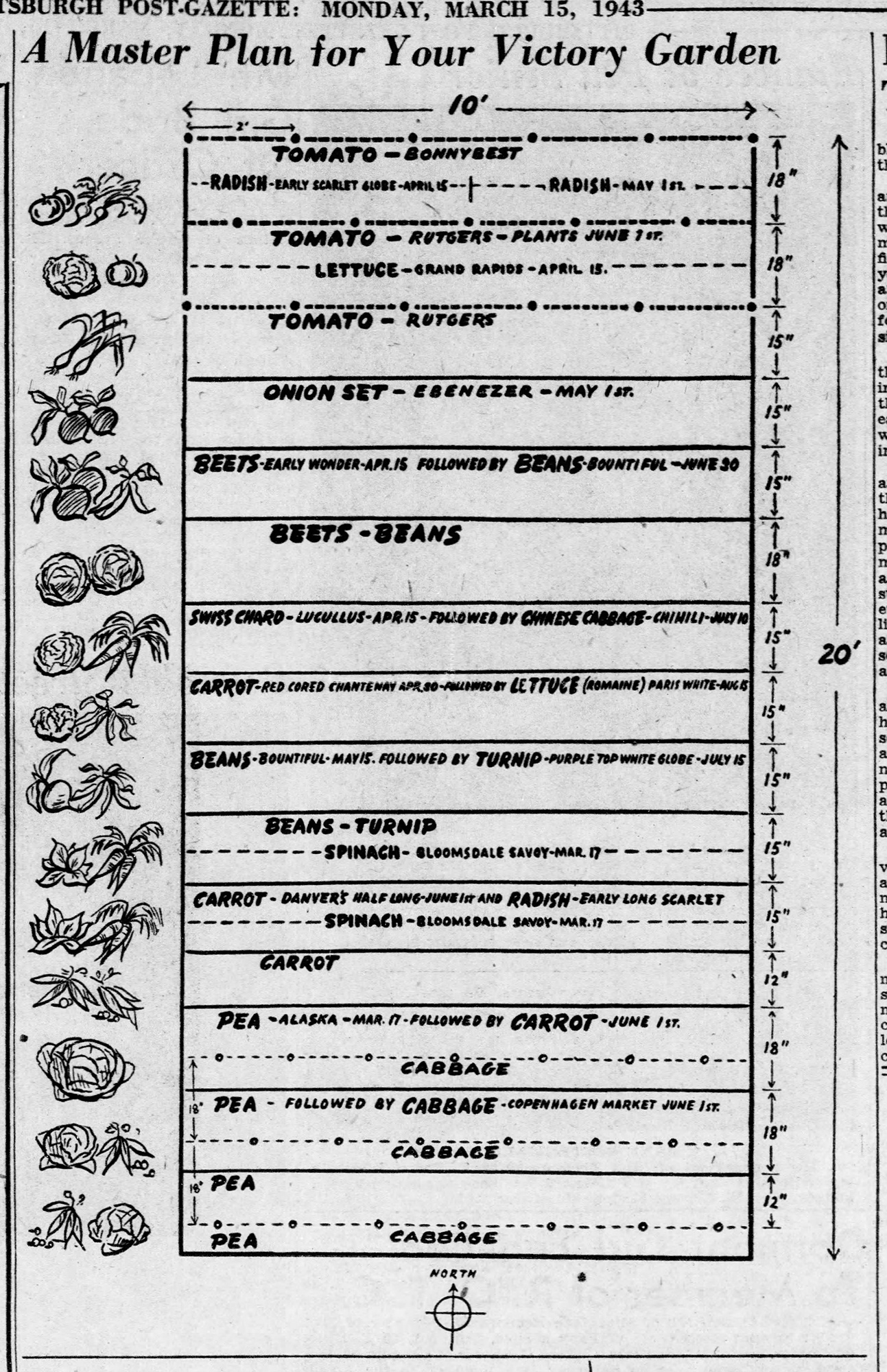

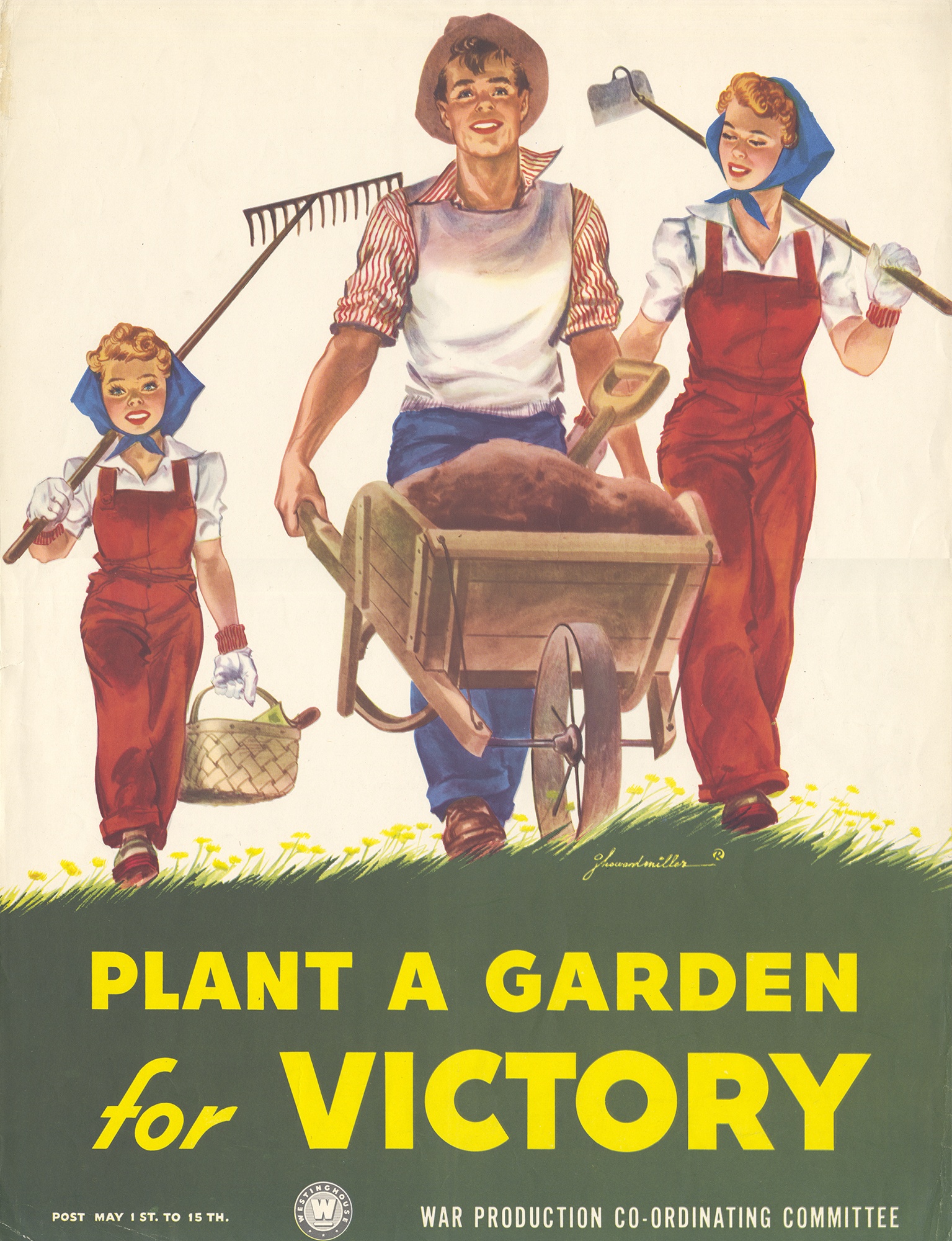

A new call for gardening started soon after the U.S. entered World War II in 1941. This gained wider prominence by early 1943 as concerns grew for the nation’s food supply and more Americans felt the impact of rationing. Officially labeled with the name that had resonated after World War I, “victory gardens” eventually became a national craze. Expanding on previous efforts, federal, state, and local governments used every technology at their disposal to urge participation and teach people how to succeed. In addition to posters, newspaper articles, and government booklets, radio broadcasts and propaganda films offered detailed advice on how to design and plan a garden, what kind of vegetables to grow, and how to plant and harvest them. (Links to two such films are included below.) The Pittsburgh Press and KDKA radio teamed up to create a model victory garden—located beside Children’s Hospital in Oakland in 1943, and in Schenley Park in 1944—then covered its development in regular radio broadcasts. Pittsburgh department stores hosted lectures, fairs, and training sessions.

With so much activity, some gardens were destined to fail. Sure enough, program numbers dipped in 1944, as some frustrated would-be gardeners decided that growing vegetables for Uncle Sam was too much work along with everything else they had to do. But overall, the initiative proved remarkably successful. At its height, victory gardening produced as much as 40% of the nation’s fresh vegetables during World War II. Again, Americans were asked to continue their efforts into peacetime due to Post-War concerns over global food supplies.

Parallels Then and Now

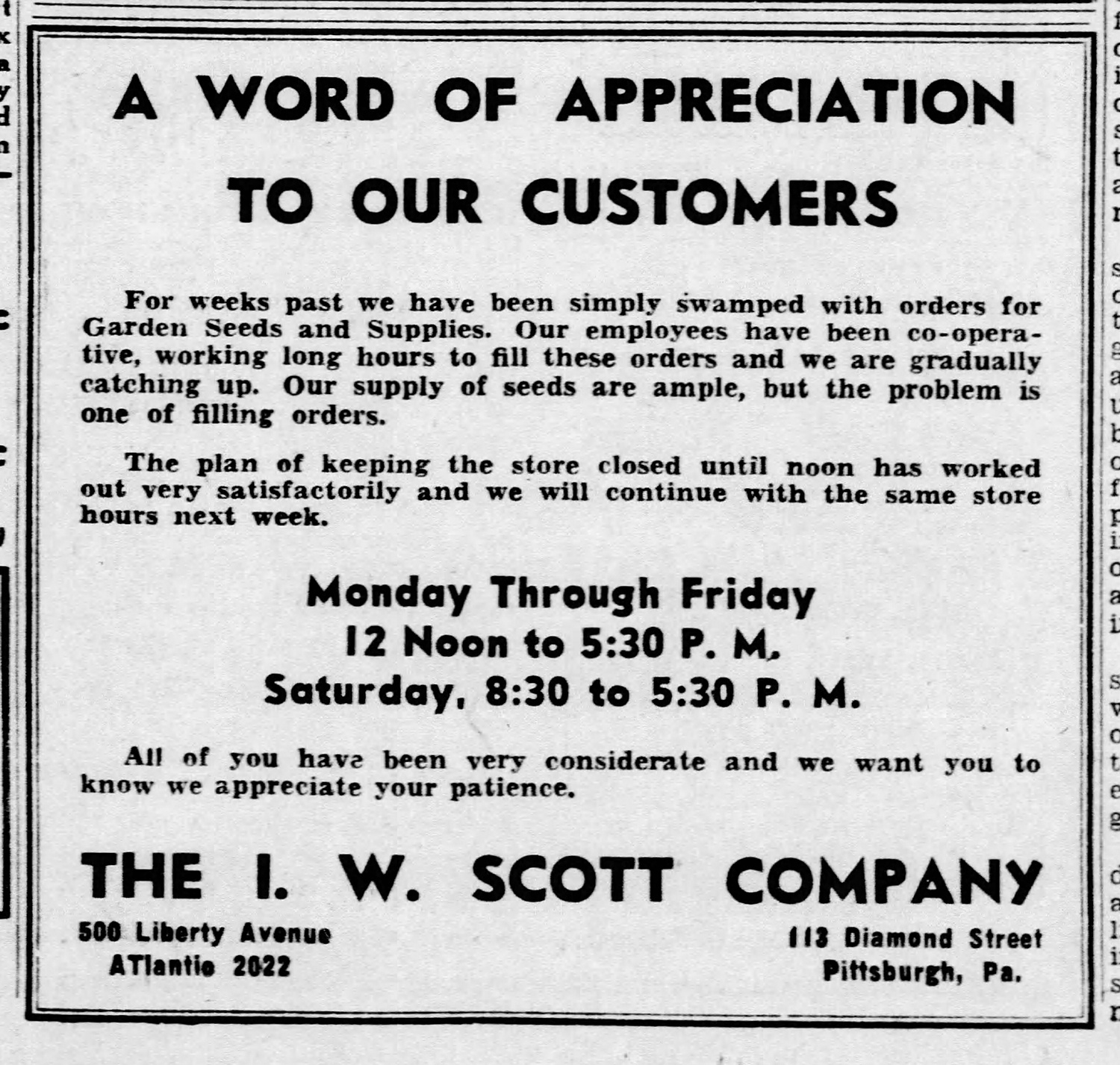

While there were clear differences in the origins and organization of war gardens, there were also parallels with the situation today. Have you tried to purchase seeds lately? Just like now, consumer demand during both wars sometimes led to a rush on seeds and supplies, with periodic shortages until the market got accustomed to the flow. During World War I, free seeds offered by the local War Garden Commission resulted in lines running around the block as people waited for their turn. During World War II, some gardening supply vendors had trouble keeping up with orders; they ran newspaper ads apologizing to their customers for the backlog.

War gardens were always about more than tomatoes, lettuce, and carrots. For one thing, the production of so much homegrown food took pressure off the nation’s strained transportation and delivery networks, whether by rail in World War I or by truck during World War II. With everything from gas to tires rationed, the creation of an alternate food source truly mattered. At times, American consumers faced very real food shortages because of disruptions in those networks. Repeated messages for people to not only grow their own food, but also preserve and can it found a ready audience, especially after the Great Depression.

And last, gardening was always seen as a marvelous morale booster and a civic contribution on par with “winning the war” through more militaristic means. It gave people something useful to do that took extended time and effort. Hours spent planning garden layouts, selecting seeds, and involving the whole family were hours not spent worrying unproductively. The fresh air, the physical activity, and the resulting vegetables all contributed to the nation’s good health.

Then as now, gardening gave people something to look forward to, a glimpse of a brighter outcome—if only fresh beans and some summer corn—when so much else seemed beyond their control.

Further Reading

World War I

To see an account of World War I’s National War Garden Commission by the man who created and led the program, check out this book from the Smithsonian Libraries:

Charles Lathrop Pack, The War Gardens Victorious. (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co.) 1919.

World War II

For another Heinz History Center Making History blogpost about food during World War II, see Food Fights for Freedom.

Multiple examples of U. S. Government Victory Garden propaganda films are available online, including:

Victory Gardens (1941/42), posted on YouTube by the FDR Presidential Library.

The Gardens of Victory (1943), from the U. S. Office of Civilian Defense and Better Homes & Gardens.

Grow Your Own (1945), from the U. S. Department of Agriculture . (Wait for the funny list of “don’t’s” at the end.)

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.