May is Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. To mark the occasion, explore artifacts from the Heinz History Center collection that speak to Asian and Asian American heritage in Western Pennsylvania. You can also check out a previous post that showcased stories highlighted in the wonderful cookie portraits of Pittsburgh artist Jasmine Cho. (Link.)

Frustratingly, items documenting this history are less numerous than other ethnic materials in the History Center’s collections. To a degree, this reflects the founding experiences of Asian communities in Western Pennsylvania and biases that lasted long after World War II.

A Chinese Community in Beaver Falls

Flatware made by the Beaver Falls Cutlery Company, c. 1875, documents the earliest story. In 1872, about 200 or so Chinese workers arrived in Beaver Falls, Pa., recruited to work at the cutlery company. Mainly men, they received four-year contracts and worked 11 hours a day, six days a week. Their hiring provoked reactions beyond Beaver Falls. The first protests came from Pittsburgh, where labor advocates feared what their arrival meant for the city’s mill and factory workers.

Many Beaver Falls residents also responded to the newcomers with hostility. The two communities mixed a little, but not much, divided by suspicion, language, customs, and racism. Men filtered away over the years and the number of workers decreased. Some left after half of them walked off the job in 1873 during a labor dispute. By 1877, the 50 or so who remained departed when their contracts expired. Many returned to California, but some headed East. Earlier this year, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC) approved a new marker that will recognize this story in Beaver Falls.

Pittsburgh’s Chinatown

While the Beaver Falls settlement dispersed, a new one formed in Pittsburgh. In the late 1800s, a full commercial district of Chinese merchants and other businesses emerged around Ross and Grant Streets, and Second and Third Avenues. Two photographs in the Detre Library & Archives depict scenes from inside a Chinatown building around 1912. The images—scenes of musicians and a ceremonial altar—capture brief moments in the life of a community that once occupied multiple blocks by the 1890s, with stores, social halls, and laundries. (Part of this was destroyed when space was cleared for the construction of the Boulevard of the Allies after World War I.)

While the community interacted with other Chinese settlements in Ohio and West Virginia, it remained a mystery to the average Pittsburgher. Knowing what sold, newspapers through the 1920s played up stereotypes of the community’s otherness by emphasizing stories of violence and “Tong Wars” and highlighting the neighborhood’s “secrecy” (largely a language divide). The press spotlighted scandalous details, such as a story from 1907 that discussed white women who had married Chinese men.[1]

But multiple generations of real people called this neighborhood and surrounding areas home. They built the same bonds as other communities, even as members began moving to other parts of town. Artifacts from the Git Lee family, donated in 2004, include materials used in the operation of a general merchandise store on Third Avenue and items that demonstrated the resilience of personal traditions. Two small anniversary bowls marked the 50th and 65th wedding anniversaries of Git Lee and his wife Lew Shee Lee, gifts distributed to guests at those celebrations. An embroidered jacket was originally given to daughter Lydia by her mother, a gesture intended to pass along the family’s Chinese heritage.

Changing Perceptions during World War II

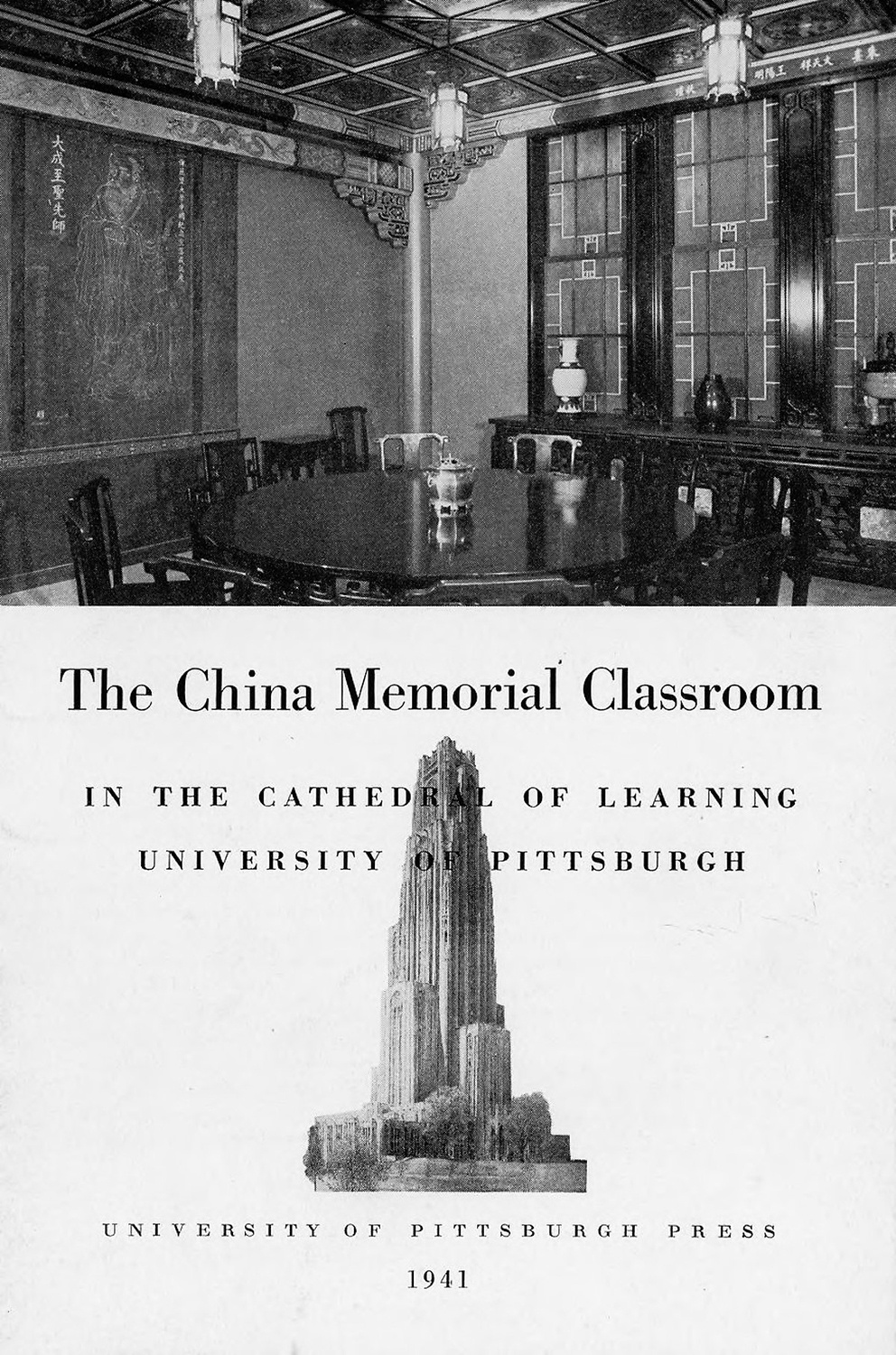

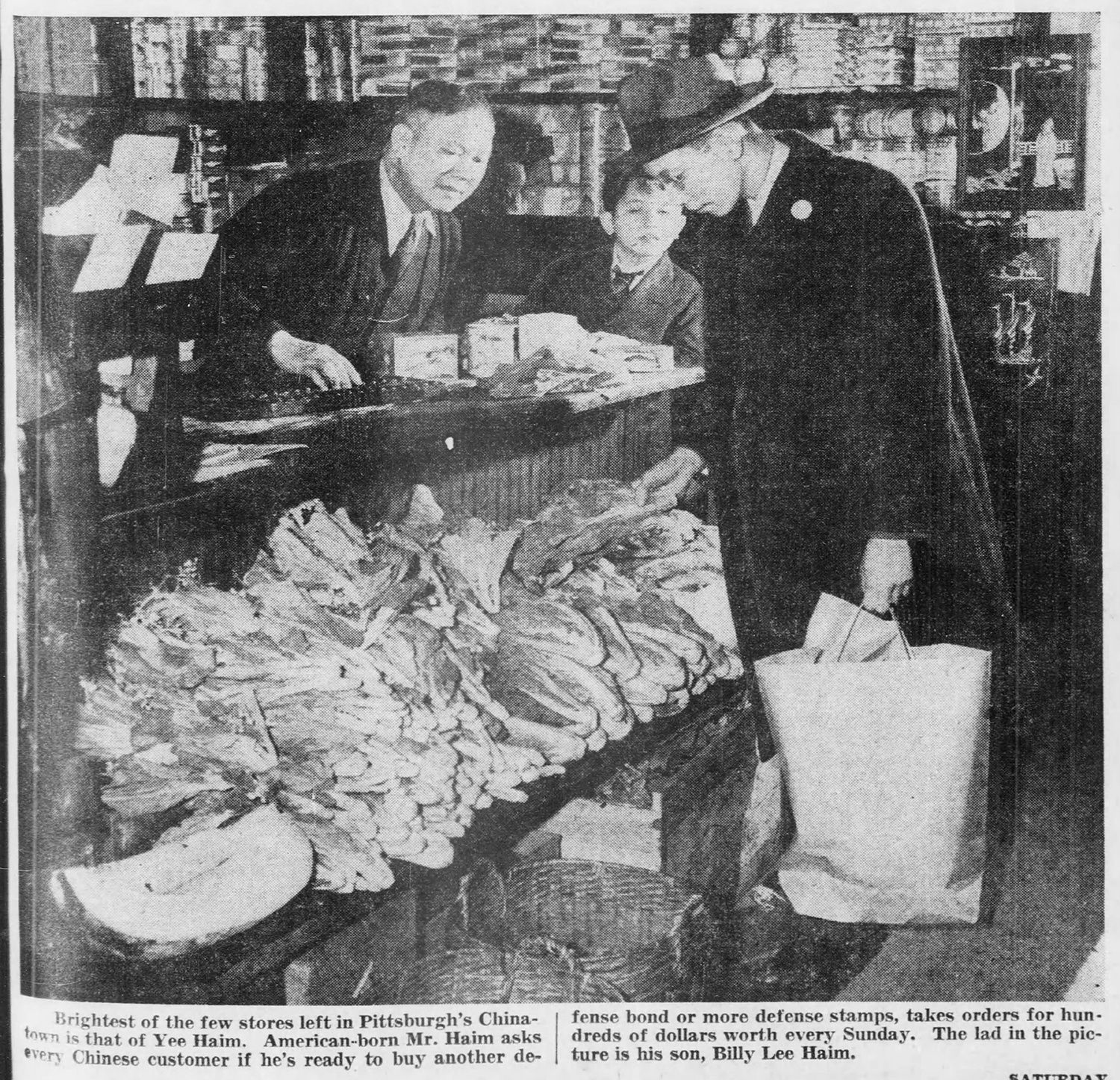

As a leading merchant, Mr. Lee was well known. He and daughters Lydia and Rosie made the local newspaper in 1944 in a feature about the celebration of Chinese Lunar New Year. Such coverage reflected a change in the portrayal of the local Chinese American community starting in the 1930s. As news broke of Japanese invasions into Manchuria in 1932 and China in 1937, the plight of the Chinese people and the American Chinese community’s efforts to support them fueled more sympathetic narratives. In 1939, the University of Pittsburgh marked the community’s long history in the region with the unveiling of the China Memorial Room in the Cathedral of Learning. By the 1940s, news features depicted a Chinatown that, while diminished in scale, was as fully committed to patriotic activities, such as buying war bonds, as Pittsburgh’s other neighborhoods.

But this convergence of local and global events presented a terrible irony. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, anti-Japanese imagery and sentiments became fundamental to America’s wartime experience. Ugly Asian stereotypes pervaded everything from Saturday matinee cartoons and workplace posters to games at children’s carnivals. (Examples of this imagery are preserved in multiple History Center collections.) Many people made no distinction between ethnicities, much less perceiving Japanese Americans as Americans. Chinese American citizens recalled being labeled and harassed as Japanese, discrimination that lasted long after 1945. As current events have shown, such twisted biases can still rear their head all too easily today.

A Wider Conversation

Increasingly since the 1960s, Western Pennsylvania’s Asian and Asian American communities have grown. Thai, Indian, Japanese, Korean, Philippine, and Bhutanese residents have added new energy and traditions. All require deeper documentation in museum collections. This growth is reflected in the sequence of new nationality rooms added to the Cathedral of Learning decades after the China Memorial Room opened in 1939. The Japanese Classroom debuted in 1999. The Indian Classroom followed in 2000. After a gap, the Korean Classroom opened in 2015, and the Philippine Classroom in 2019. A Thai Classroom has also been proposed. (A Bangkok university features its own Cathedral of Learning modeled after Pitt’s landmark. Link.) After multiple tries, the PHMC also recently approved a new marker recognizing Pittsburgh’s Chinatown, making 2021 a crucial year with the approval of two markers addressing this history in Western Pennsylvania.

The History Center seeks to continue collecting materials that document the diversity of Asian American experiences. The recent holiday exhibition A Very Merry Pittsburgh included the classic red envelopes of the Chinese Lunar New Year and the distinctive lamps used in the Hindu celebration of Diwali. The latter joins other material in the museum collection addressing the impact of the region’s Indian population, an increasingly important community here since the 1970s with its own trajectory and customs deserving of a much closer look.

As these groups continue to grow and prosper, gathering more artifacts documenting their stories takes on new urgency, ensuring that the History Center continues to preserve and display a collection truly reflective of the peoples and heritage shaping our region into the 21st century.

These small earthenware lamps are central to the Hindu religious festival Diwali. The light of the lamp drives away darkness and symbolizes knowledge. Usually filled with oil or ghee and lit with a cotton wick, the lamps light the home, burning away darkness and ignorance, as the flame reaches towards higher spiritual knowledge. Gift of Krishna Sharma, Heinz History Center Museum Collections.

For Further Reading

About the Beaver Falls story

“UCIS researcher uncovers little-known local history: Labor dispute brought first Chinese to area in 1872,” University Times (University of Pittsburgh), December 4, 1997. Available online.

Marsha Keefer, “‘An absolute treasure’: Rare Chinese manuscript found in closet of Beaver Falls Historical Museum,” The Times, March 9, 2012. Available online.

About Pittsburgh’s Chinatown and Anti-Asian Bias

Kathleen J. Davis, “What happened to Pittsburgh’s Chinatown?” WESA’s Good Question series, February 14, 2019. Available online.

Kimberly Rooney, “Anti-Asian hate crimes don’t begin with physical violence,” Pittsburgh City Paper, February 25, 2021. Available online.

[1] “Scandal in Chinatown, White Wives of Orientals get into Fierce Fight,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, July 23, 1907.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.