When does the Christmas season begin? For retailers these days, the answer seems to be “as soon as possible.” While the weekend after Thanksgiving has long served as the unofficial start of the holiday season, other days also held that title.

For Pittsburghers of Christian European descent, especially German, Dec. 6 was a special day each year. Children awoke to find their shoes or stockings filled with fruits, nuts, chocolate coins, and other treats, a gift from Saint Nicholas in honor of his feast day.

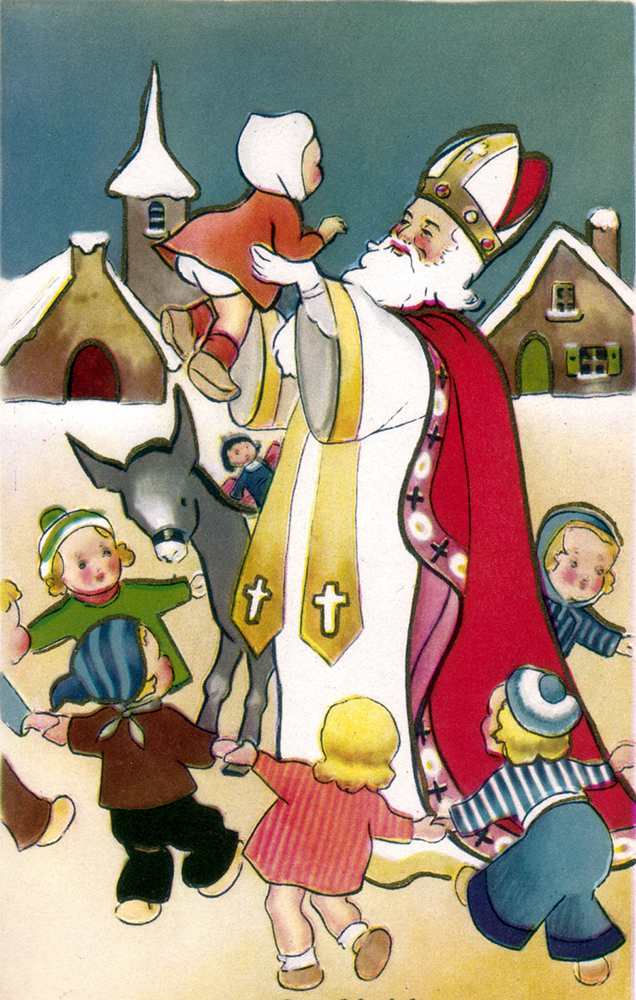

“St. Nicholas Day” was the kickoff for a whole month of celebrating. Unlike Santa, Saint Nicholas was based on a real person, although little is conclusively known about him. Nicholas was supposedly a wealthy young man from Asia Minor who became Bishop of Myra, a Mediterranean city in what is now Turkey. Generous with his money and courageous in his defense of Christianity amidst years of Roman persecution, Nicholas was revered after his death. Eventually the anniversary of his passing, Dec. 6, became a Christian feast day. This celebration intermingled with other regional traditions and spread across Europe, Greece, and Asia Minor. Called Sankt Nikolaus in German or Sinterklaas in Dutch, St. Nicholas became a precursor to our modern Santa Claus. The two clearly resemble each other, although St. Nick’s bishop’s hat gives away his liturgical origins.

Variations on St. Nicholas Day cards, c. 1900s. St. Nicholas Day cards were common in Germany, Austria, France, Belgium, and other European countries. The images of these cards are courtesy of The St. Nicholas Center.

Multiple immigrant groups brought St Nicholas Day with them to the United States. The practice rooted deeply in American cities with heavy German populations. Pittsburgh joined Cincinnati, Milwaukee, and St. Louis in awaiting “St Nick’s” arrival each year. (Similarly, Pittsburghers of Eastern Orthodox faiths celebrated St. Nicholas Day on Dec. 19 each year.)

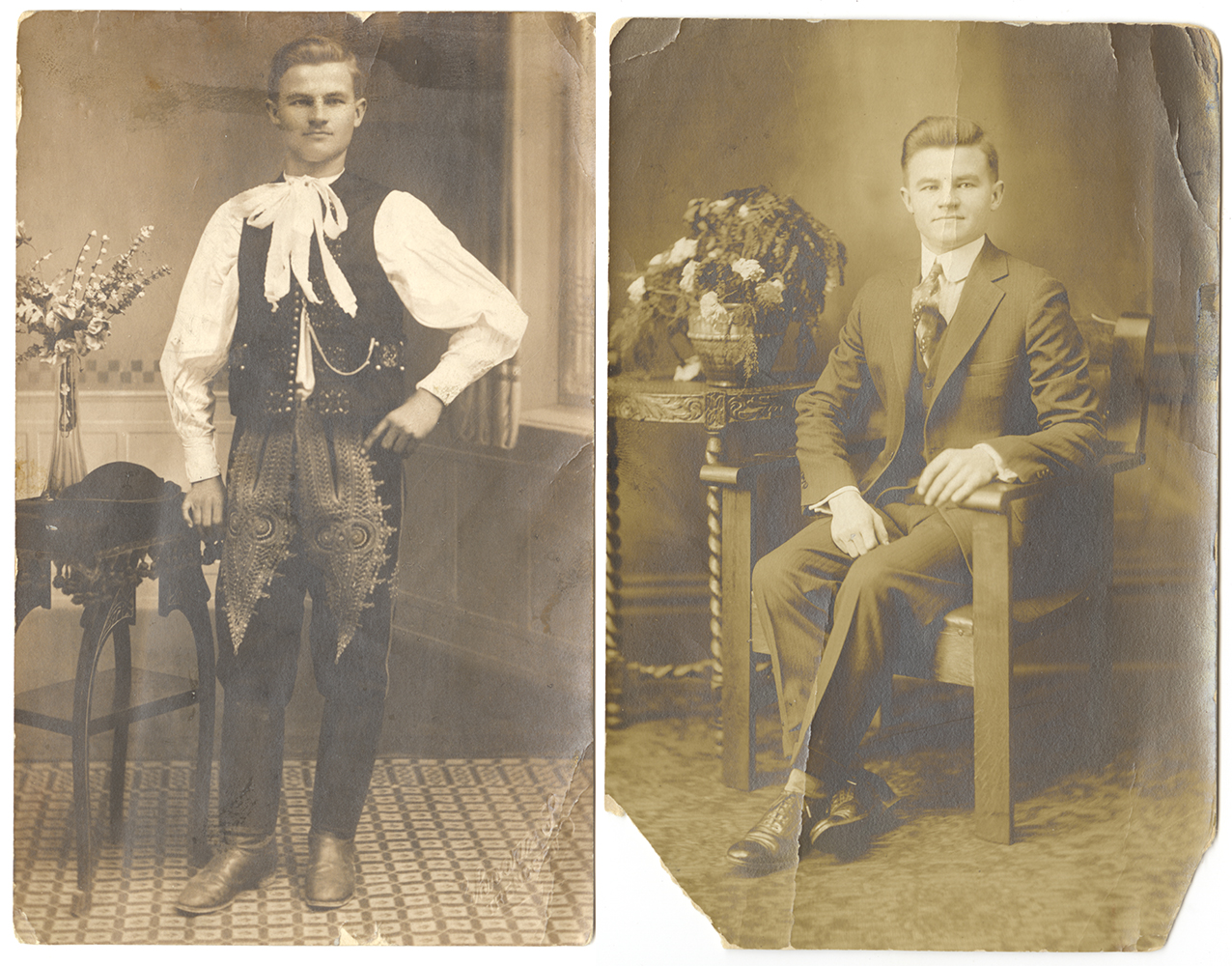

In multi-ethnic, industrial Pittsburgh, St. Nicholas Day was one more meaningful reminder of the many cultural practices that people sought to preserve in their new homeland. From Polish szopki – elaborate portable nativity scenes paraded through city streets and used as puppet theaters – to Italian pizelle cookies – those delicate anise-flavored wafers especially prized during the holidays, Pittsburgh’s ethnic communities celebrated the holiday season by carrying on their own traditions amidst the hustle and bustle of Christmas in a large American city.

Photo from the Detre Library & Archives at the Heinz History Center, gift of Lillian Hasko.

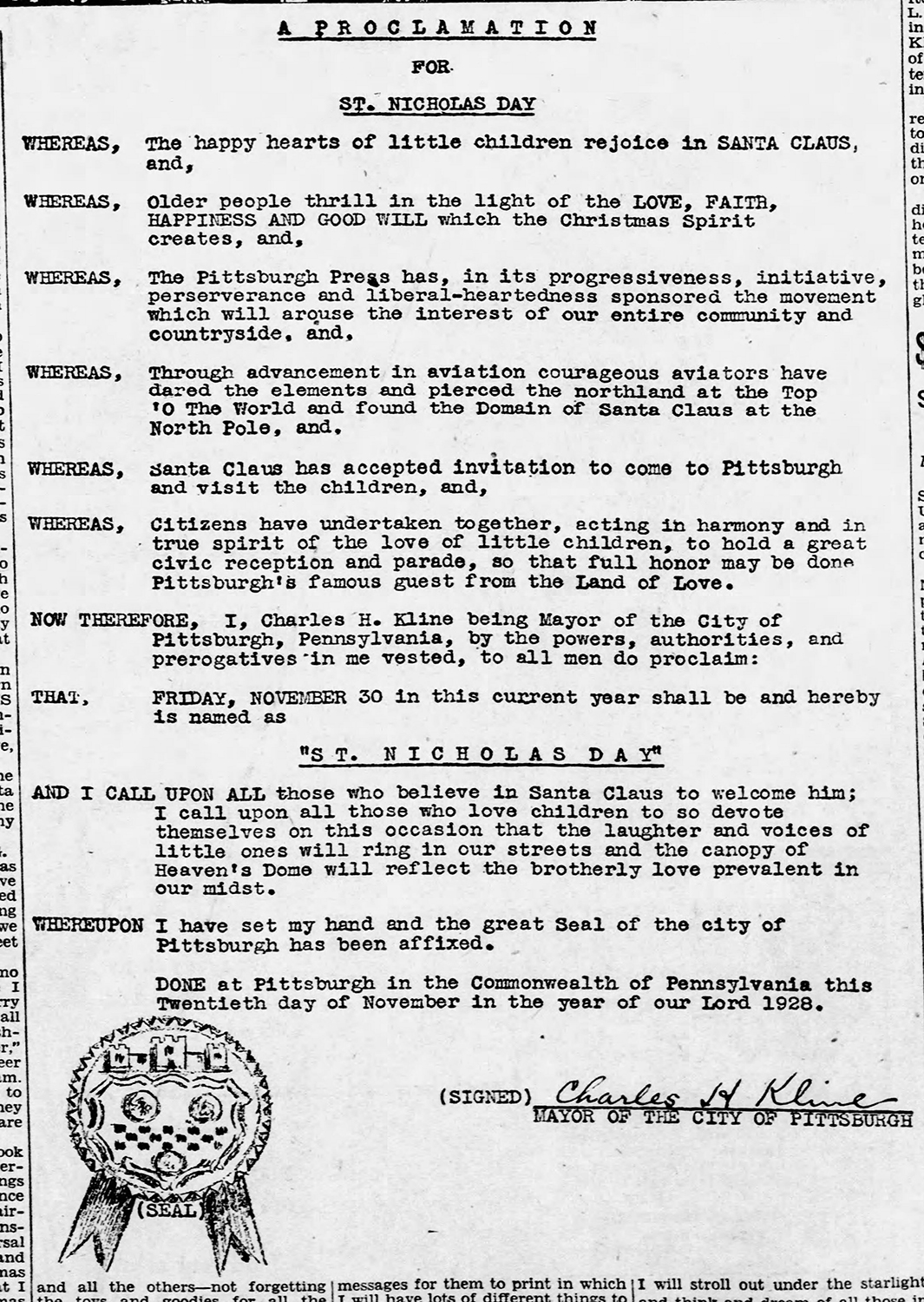

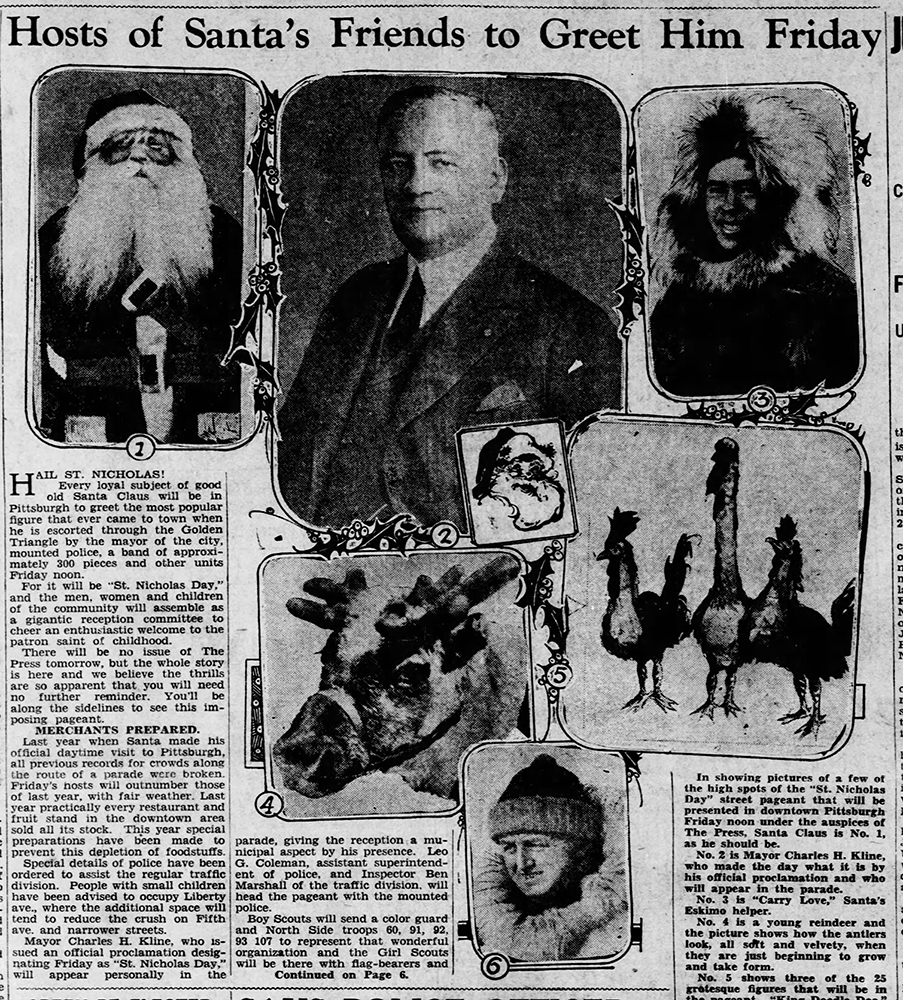

Sometimes boundaries between traditions got a bit confused. Through the 1920s, Pittsburgh mayors and city officials annually announced their own “St. Nicholas Day.” With a date ranging from Nov. 30 to Dec. 3, this version served as the official kick off for the holiday season, sometimes announced by proclamation in local newspapers. The names “St. Nicholas” and “Santa Claus” were used interchangeably, although phrases lauding the “courageous aviators” who pierced the domain of the North Pole at the top of the world leave no doubt as to who was on everyone’s mind. In fact, the two figures had grown increasingly synonymous in American culture since the publication of the poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (or “The Night Before Christmas”) in 1823, in which the character of Old St. Nick was simply described as being dressed “all in fur” from his head to his foot, no Bishop’s mitre in sight. By the 1920s, the Americanized holiday mixed everything together. In 1928 Pittsburgh, Santa was joined in the “St. Nicholas Day” festivities by a real reindeer and a few Eskimo helpers. Nonetheless, the mingling of the names demonstrated the historical connection between the two figures. It was also an ongoing reflection of the city’s deep German heritage.

The holiday balancing act between ethnic identity and American identity was something on everyone’s mind during the 1920s, including local corporations. In Braddock, the Edgar Thomson Steel Works invited thousands of their employees’ children to visit their main office each year for a special Christmas treat. Photographs show lines of children – there were 8,000 in 1923 – parading in front of a huge Christmas tree, each of them clutching a bag filled with candy and popcorn balls. Given the many ethnicities represented in the Edgar Thomson Works, many of these children probably went home to a wide variety of their own Christmas celebrations, including Polish, German, Italian, Hungarian and Slovak. But when they opened those bags of candy and popcorn balls at home, the mill that shaped their lives had sent a clear message about its holiday aspirations for the next generation: those Christmas popcorn balls were red, white, and blue.

For further background on the relationship between St. Nicholas and Santa Claus, see:

Brian Handwerk, “St. Nicholas to Santa: The Surprising Origins of Mr. Claus,” National Geographic, December 20, 2013.

The website of the Saint Nicholas Center in Holland, Mich., featuring a wide range of historic images, ephemera and information about cultural practices connected with Saint Nicholas around the world.

Leslie Przybylek is curator of history at the Heinz History Center.