One of the most striking portraits on display in the History Center’s current exhibition, Smithsonian’s Portraits of Pittsburgh: Works from the National Portrait Gallery, depicts famous jockey Bill Hartack suited up for a horse race and standing in front of a row of racing silks. Artist James Ormsbee Chapin painted the image for the cover of TIME magazine, where it appeared on Feb. 10, 1958. For Hartack, the son of a Western Pennsylvania coal miner and who became known as the “million-dollar kid from Cambria County,” 1958 loomed as a banner year. But his luck soon ran out.

A way out of the mines

After graduating from rural Blacklick Township High School in Nanty-Glo, Pa., Hartack eventually ended up at West Virginia’s Charles Town racetrack as an exercise rider. Family friends suggested that he look for a job at the track after his father, who worked for the Ebensburg Coal Company, insisted that his son never follow him into the mines. Hartack’s small frame and competitive nature proved perfect for the track. In 1952, an astute trainer recognized his skill and offered him a riding contract as a jockey. Although he started slowly, he began winning regularly in 1953. By 1954 he started riding at major tracks and soon enjoyed a meteoric rise. From 1955-1957 he was the nation’s leading jockey based on races won. He rode his first classic winner, Calumet Farm’s Fabius, to victory in the 1956 Preakness Stakes. A year later, he won his first Kentucky Derby with Calumet’s Iron Liege. In 1957, he became the first jockey to win more than three million dollars in a single season.

The year takes a turn

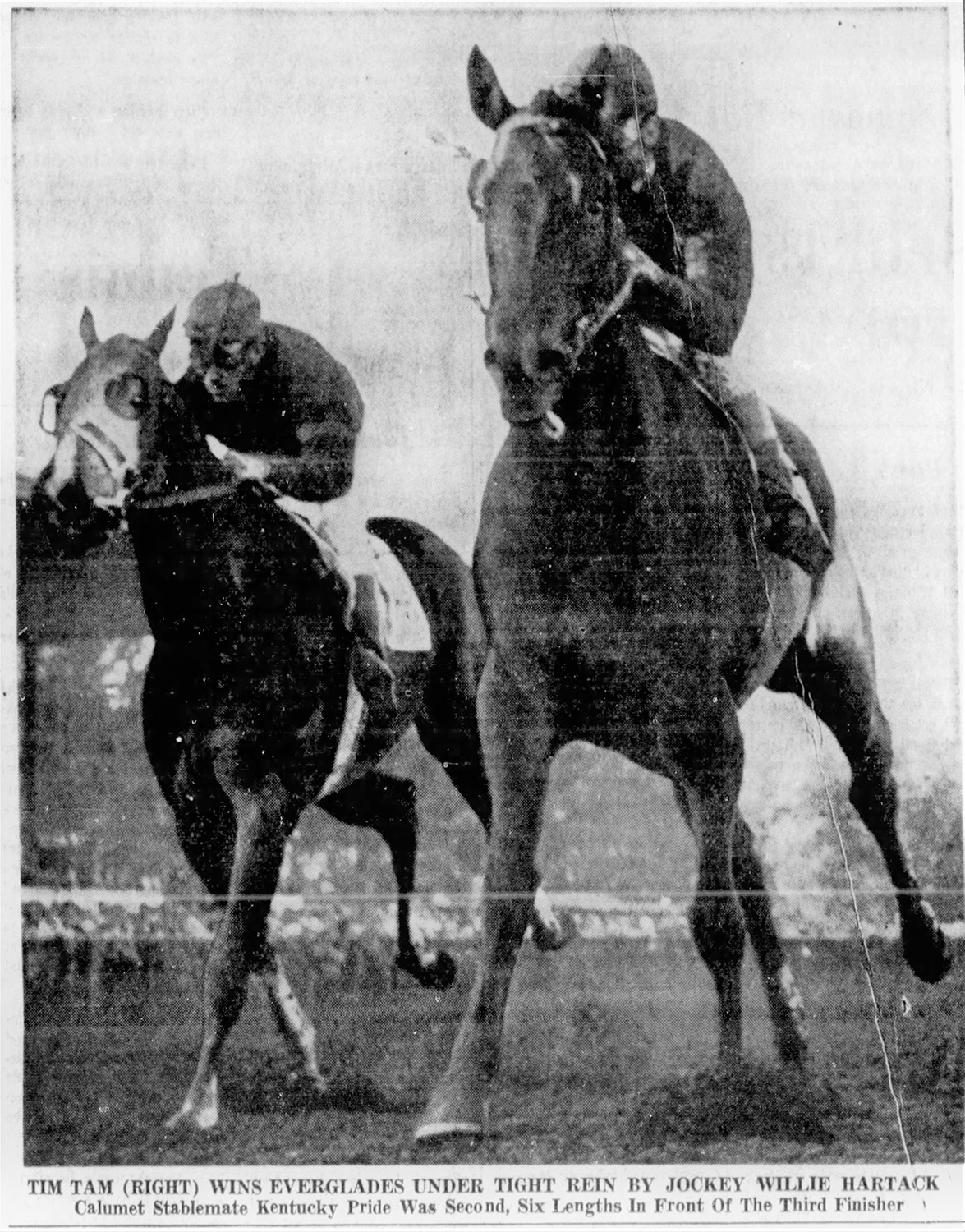

In the spring of 1958, Hartack looked ahead to the possibility of back-to-back Derby victories with an exciting new Calumet colt, Tim Tam. Just six days after that TIME cover, the pair won Hialeah’s Everglades Stakes. Tim Tam quickly emerged as the Derby favorite. With Hartack up, he won five more stakes that spring in preparation for the first Saturday in May.

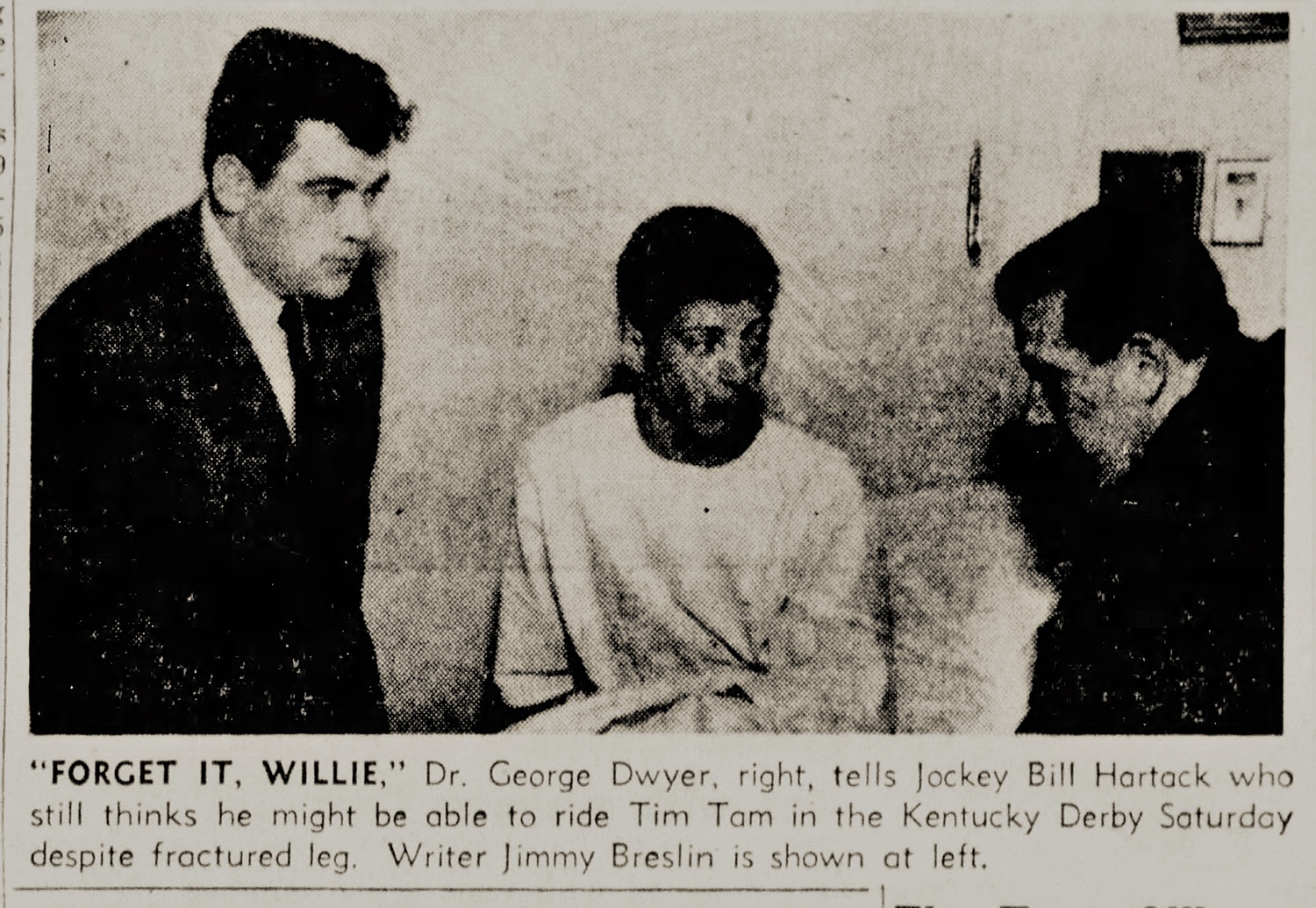

But Hartack’s luck changed on April 26, 1958. In the starting gate before a race at Churchill Downs, his mount reared and he fell off backwards, breaking his leg. Hartack insisted that he could still ride. News accounts illustrated his fighting spirit. “Don’t let them put anything heavy on my leg,” he supposedly told his agent when he was loaded into an ambulance. “Get a light cast and we’ll gallop a horse Thursday and by Saturday I’ll be ready.”[1] He tried to have a special cast and stirrup made.

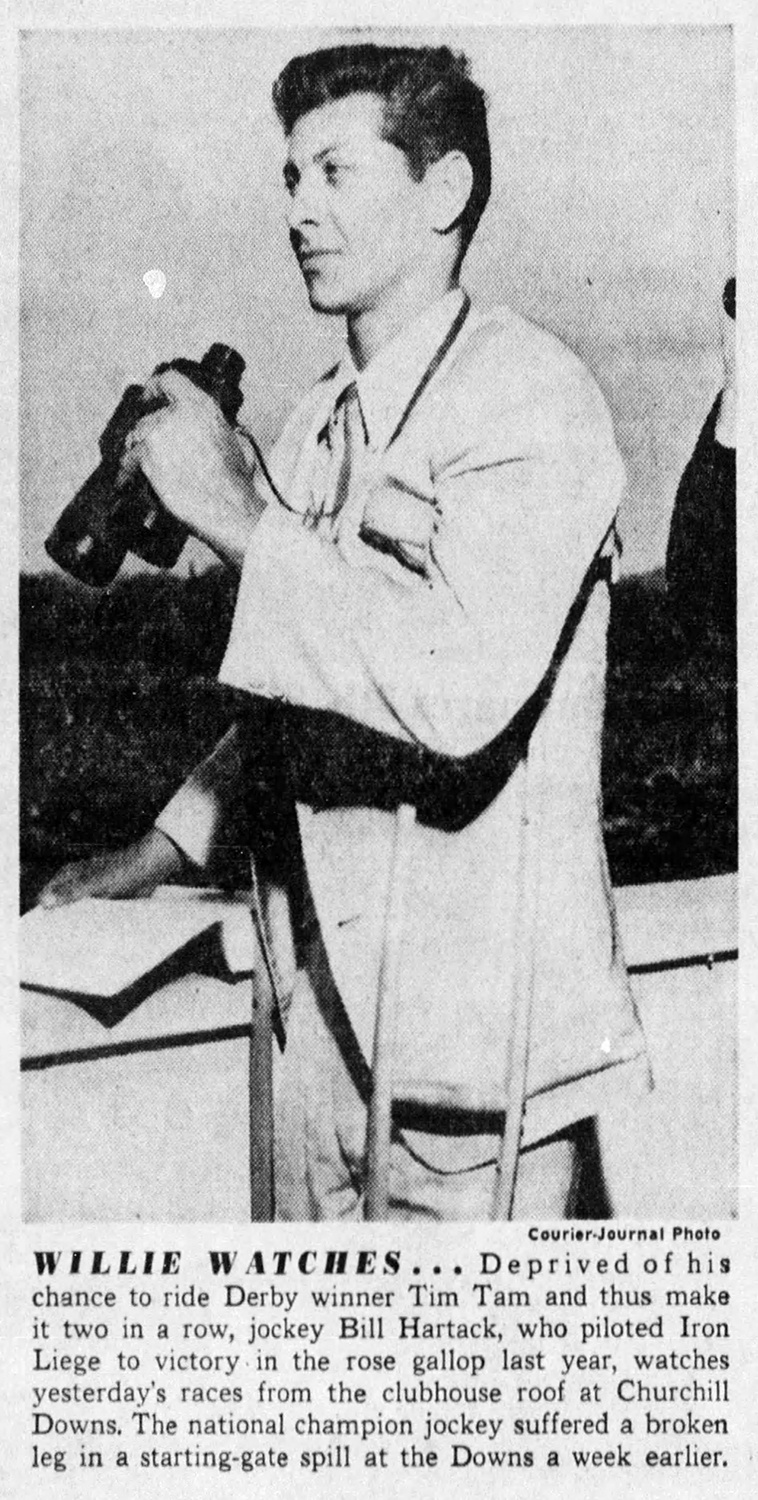

It was a losing battle. Doctors would not let him ride. Hartack watched the race from the Clubhouse roof at Churchill Downs as someone else guided Tim Tam to the coveted Derby win. But the broken leg did not keep him down for long. By May 20, 1958, Hartack was riding again.

Hartack eventually became a four-time national champion jockey and the only rider besides Eddie Arcaro to win the Kentucky Derby five times. He was inducted into the National Racing Hall of Fame in 1959 at age 27, the youngest in history. Illustrative of horse racing’s wide popularity at the time, he even appeared on an episode of the TV game show “What’s My Line?” in 1964. (Watch online.)

Horse Racing’s Ted Williams

The 1958 episode illustrated one of Hartack’s greatest assets but also his biggest liabilities. The same relentless drive that made him a winner sometimes made him go too far. Combative and opinionated, he disliked criticism and had a difficult relationship with the media. Some started calling him the “Ted Williams of horse racing,” in comparison with the great baseball player also known for his battles with the press.

While critics and racing historians felt Hartack could have become more popular with a more congenial personality, he continued to serve the sport he loved in other capacities for the rest of his life. After his death in 2007, his many friends in the industry established a charitable foundation in his name. Every year, the winning jockey of the Kentucky Derby receives the Hartack Memorial Award. On a more local level, Hartack was also inducted into the Cambria County Sports Hall of Fame in 1971.

Ultimately, that striking TIME magazine cover also illustrated Hartack’s sometimes bullheaded nature. He preferred going by “Bill” or “William,” and hated “Willie.” He insisted that no one use it, although everyone did. Despite the great image on the cover of that 1958 TIME, Hartack refused to ever sign autographs on it. TIME called him “Willie.”

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center and lead curator on the Smithsonian’s Portraits of Pittsburgh exhibition.

[1] Jimmy Breslin, “Hartack Clings to Derby Hope,” The Pittsburgh Press, April 28, 1958.