On April 23, 1945, Pittsburgh’s legal landscape bustled with activity. As a U. S. Grand Jury convened at the federal courthouse, Montana Senator Burton K. Wheeler, chair of the Senate’s War Food Investigation Subcommittee, marched into town to conduct hearings. Both focused on one issue: black-market meat in Pittsburgh. They were responding to headlines garnered by Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporter Ray Sprigle, who set out in the Spring of 1945 with his old truck, “a bundle of cash,” and a healthy dose of persistence to see how much illegal meat he could round up around Pittsburgh. Ranging within a 30-mile radius, he gathered more than a ton of illicit steaks, chops, and other cuts.

Today, the coronavirus pandemic has closed meat processing plants across the nation, including two in Pennsylvania. The closures raise new concerns about the nation’s meat supply as grocery store customers already confront empty shelves. As we face this latest challenge to the American dinner plate, it is useful to reflect upon what happened 75 years ago, when a different set of circumstances forced people to contemplate a change in eating habits. Why was black market meat such a problem during World War II, and what prompted Ray Sprigle to wade into the fray?

Share the Meat

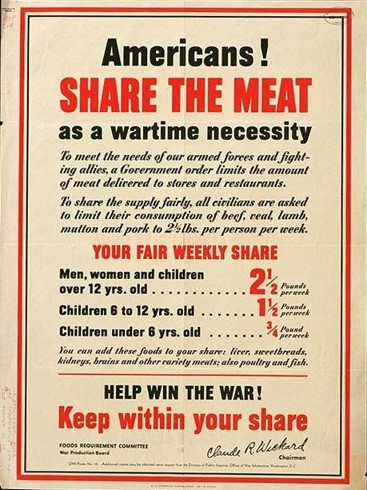

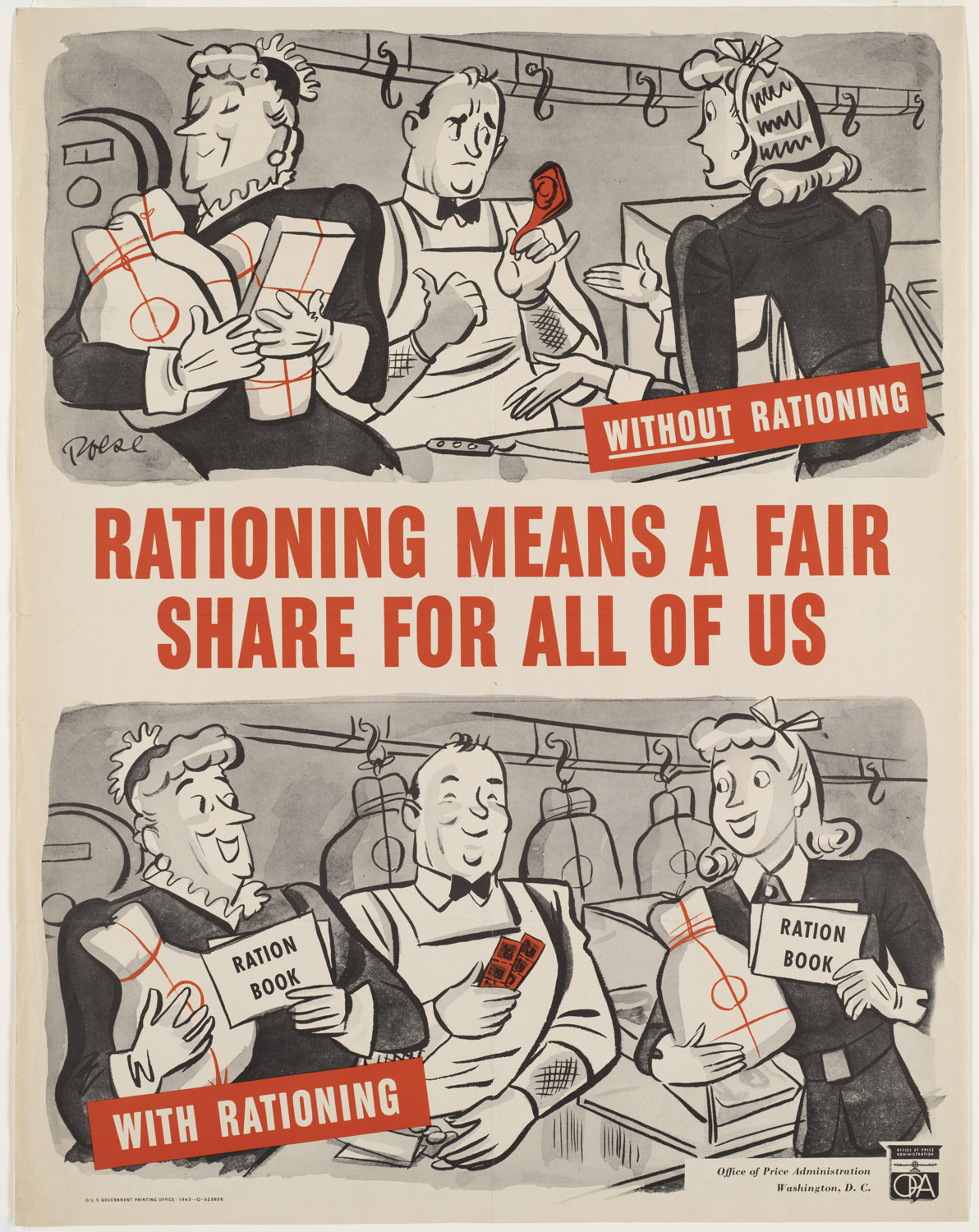

Facing lend-lease obligations to Allies such as Great Britain and the need to feed American troops, U. S. officials knew the meat supply would be threatened during World War II. They also recognized meat as a key part of the American diet, a symbol of success and national identity. People would not give it up easily. They first tried a soft approach. In 1942, the United States launched a voluntary “share the meat” campaign, asking everyone over age 12 to limit consumption to 2 1/2 pounds per week. It was not enough. By March 1943, meat was added to the nation’s ration list.

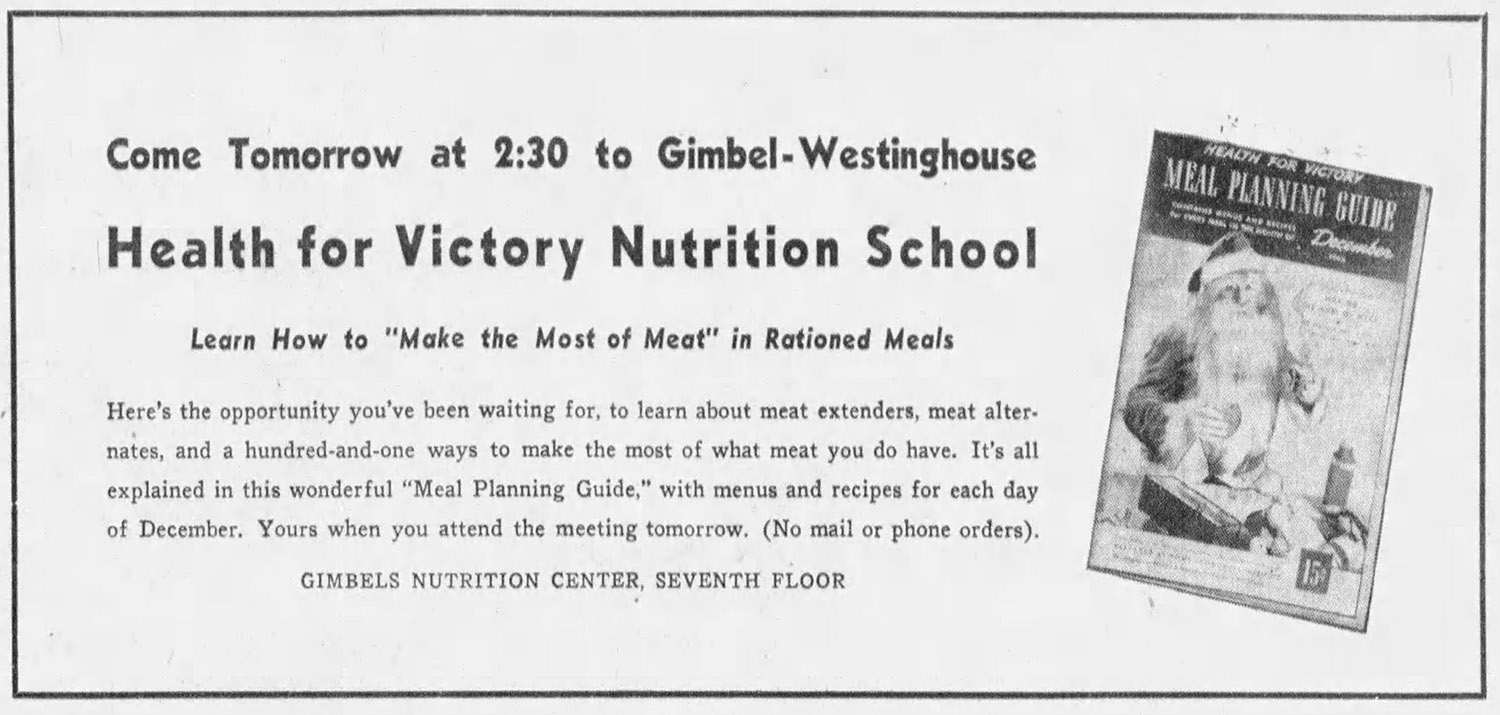

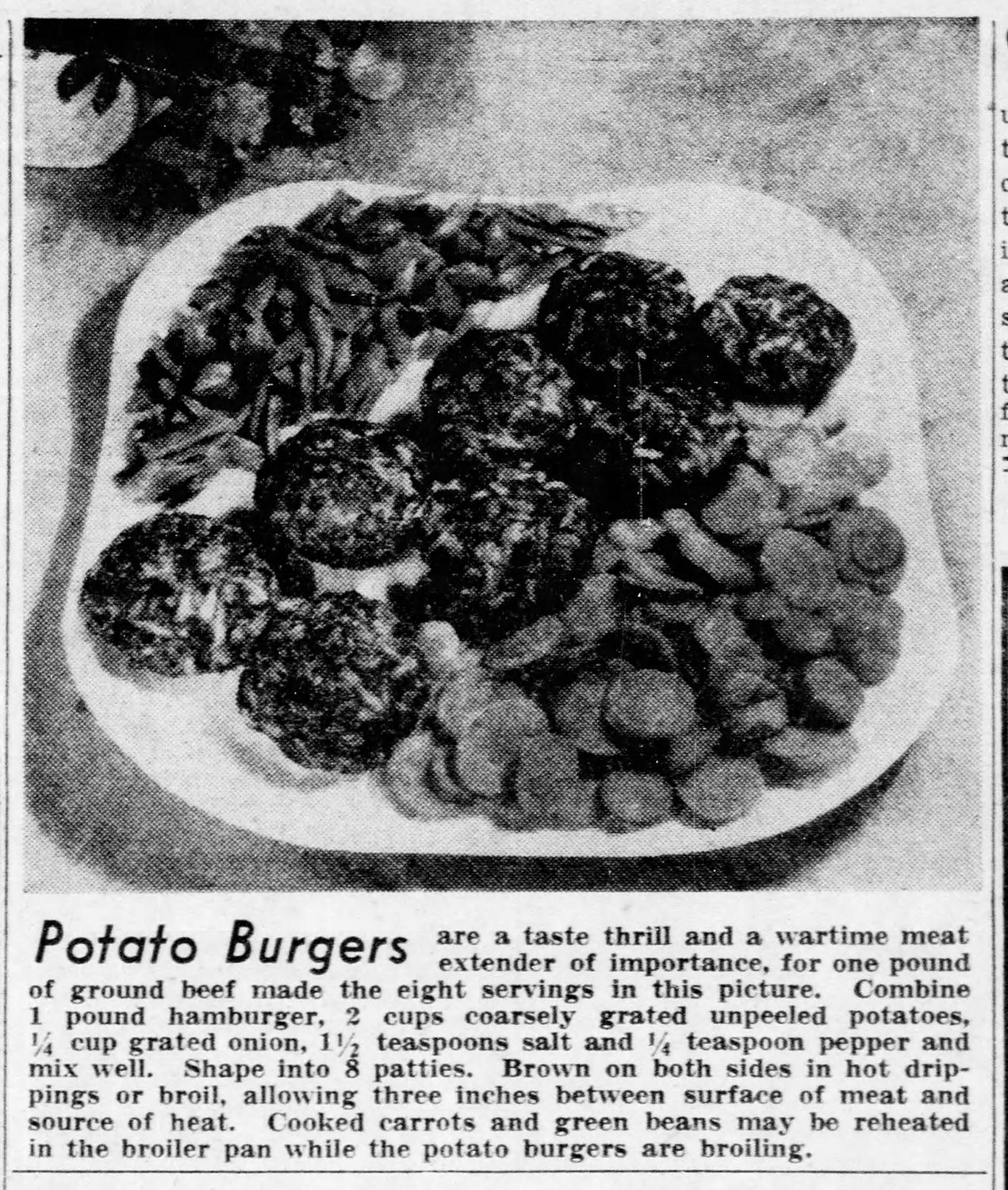

In truth, many protein sources remained, including eggs, peanut butter, soy products, beans, and cheese. Dietitians, national meat councils, and local authorities touted “meat-extending” recipes that combined meat with potatoes, rice, gelatin, and other fillers to stretch rations. They stressed that “variety meats,” including liver, heart, and kidneys, were plentiful, unrationed, and tasty. Most Americans, unless already accustomed to such ingredients, disagreed. Some meats were unrationed, including sausage, bologna, and small game. But consumers faced limits and shortages on the meat that mattered most: beef, especially steak, as well as pork, veal, and lamb.

Supply and Demand

Meat scarcity arose from a complicated mix of rationing guidelines, agricultural supply cycles, and laws regulating meat processing, pricing, and sales. Critics charged that the policies of the Office of Price Administration, or OPA—the agency that oversaw rationing—inflamed the situation. Large meat suppliers knew they could ask for higher prices from the U. S Government for military needs, so sold less to the general consumer market with its lower price ceilings. At times, good cuts of meat became impossible to find. Meanwhile, independent operators bought and slaughtered animals clandestinely, selling the meat on the black market at higher prices, no ration points needed.

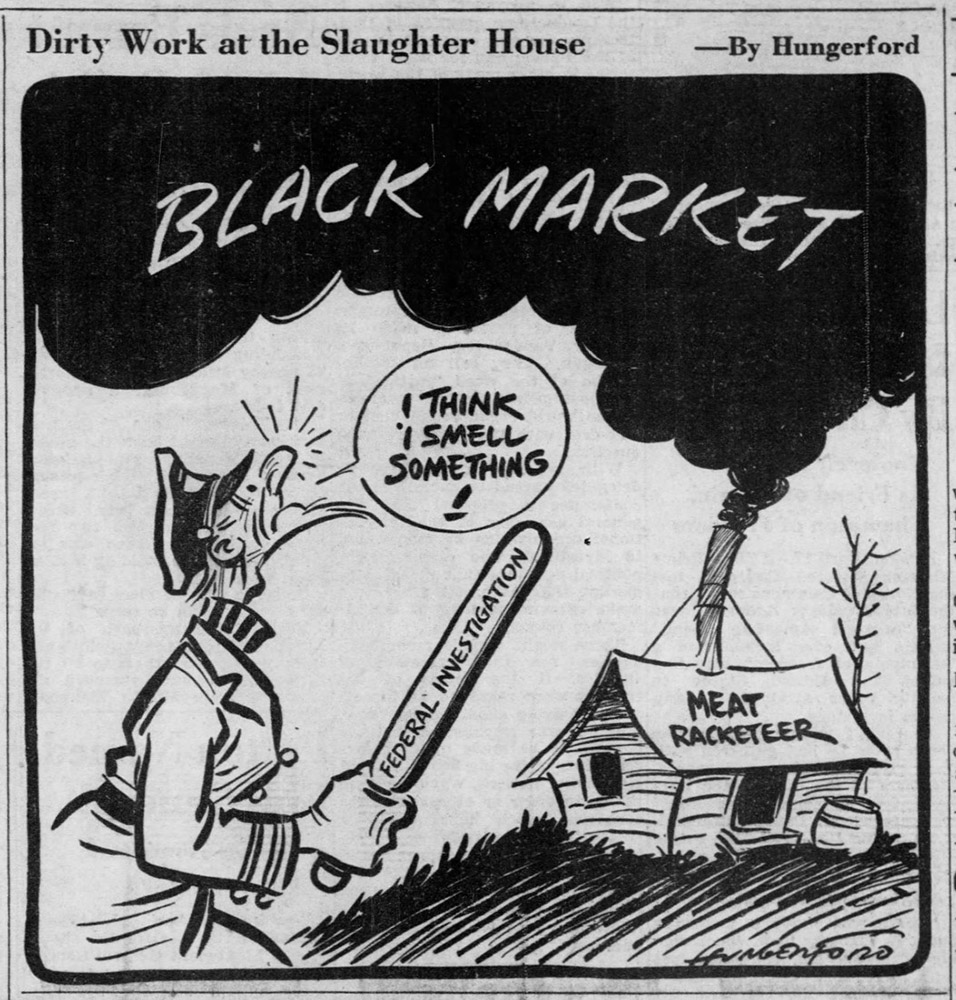

Theoretically, the OPA enforced the rules. They seemed hesitant to do much. In cities like Pittsburgh, illegal operations flourished. For many Americans, the situation evoked memories of Prohibition and they acted accordingly. Headlines called black market meat operators “meatleggers.” Early reports linked their activities to “Al Capone’s gang.” (This turned out to be untrue.) The federal government tried endless public messaging to encourage cooperation, including radio announcements and a propaganda film, a gangster-inspired flick called “Black Marketing.” The popular radio show “Fibber McGee and Molly” featured a black market meat storyline (everyone who ate illegal meat got sick), as did a 1944 comedy film, “Rationing,” starring Wallace Beery. The problem went in cycles, sometimes better, sometimes worse; it never disappeared. American attitudes ran counter to their northern neighbors. Canadians also faced meat shortages but proved less prone to black market activity.

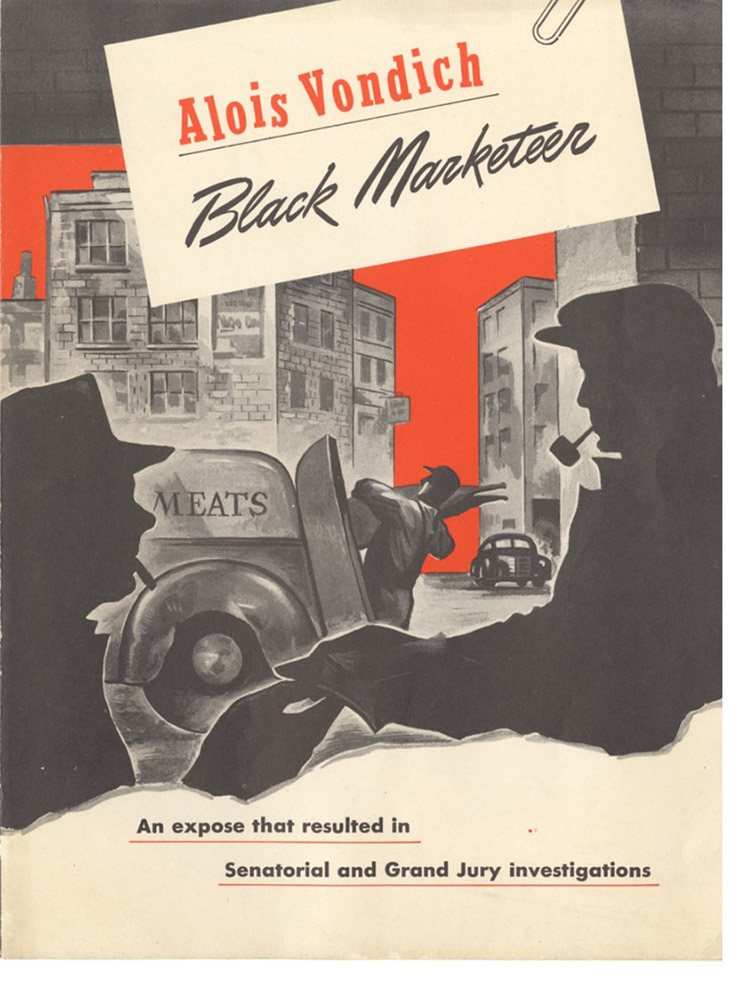

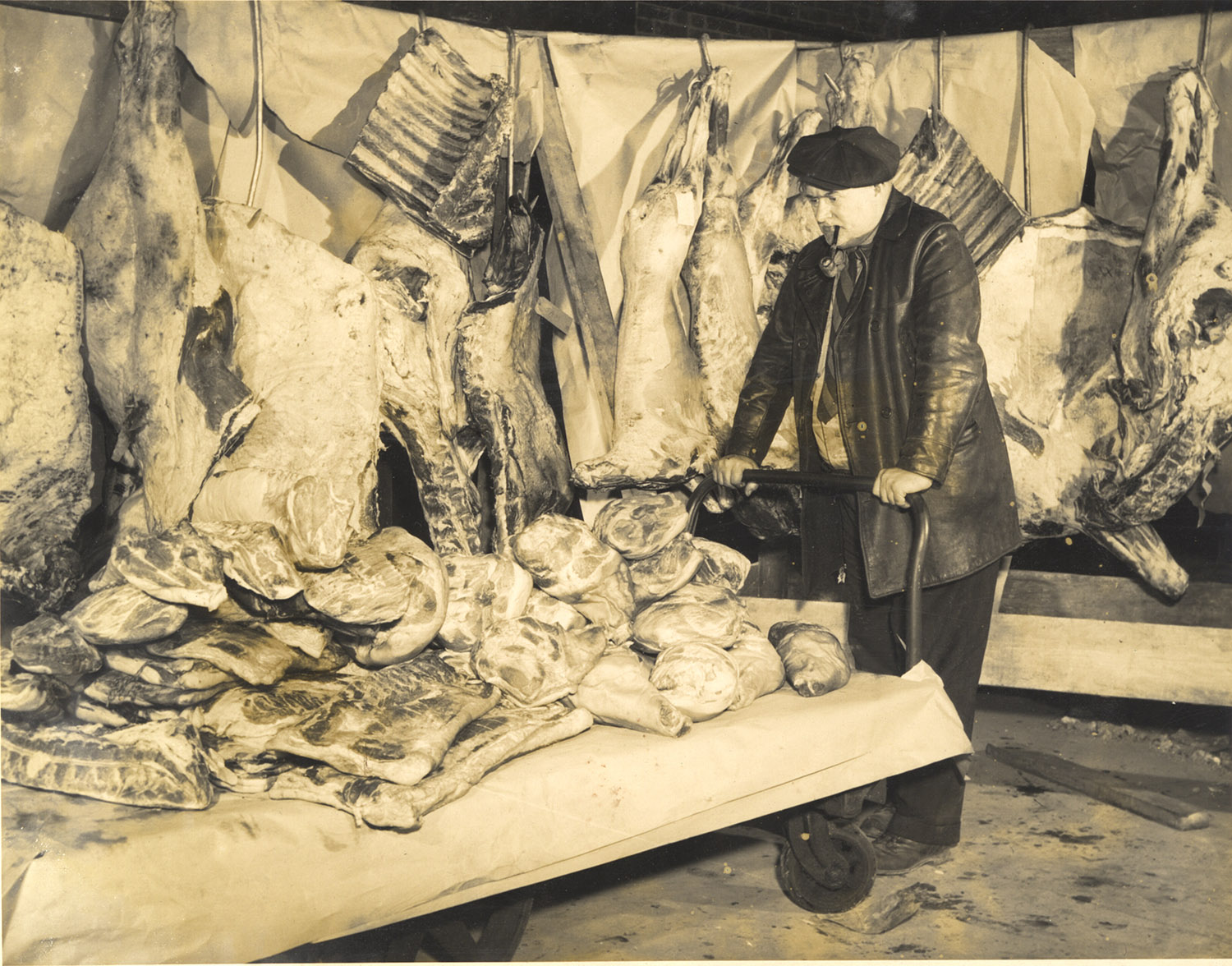

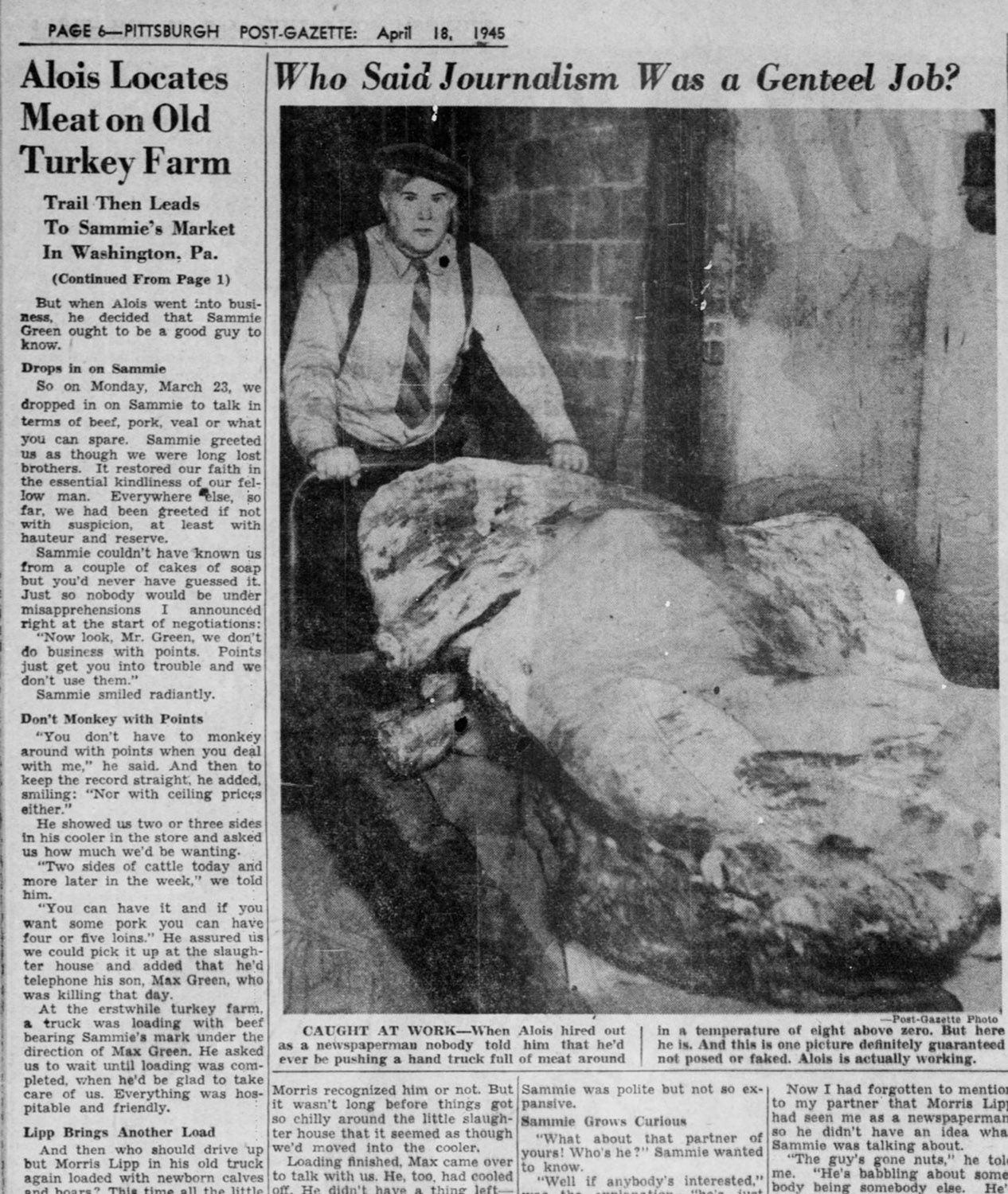

Alois Vondich, Black Marketeer

By Spring 1945, an especially severe meat shortage prompted Ray Sprigle to act. Famous for his undercover investigations, Sprigle decided to blow open the situation in Pittsburgh and reveal the OPA’s ineffectiveness by rounding up as much black market meat as possible. Posing as a buyer from Cleveland named “Alois Vondich,” Sprigle began his operation in late March. Slowed by an early Easter (the holiday demand for meat was so great that little was available for new customers), Sprigle eventually visited wholesale grocers, community markets, and back alley dealers from McKeesport to Canonsburg, hauling in more than a ton of illegal meat. His findings ran in a seven-part series on the front page of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and twenty-two other newspapers as well as Time magazine in April 1945.

Problem solved or not?

Sprigle got headlines and results, but not the conclusive solution he desired. The Grand Jury indicted some of the black market dealers, and the OPA, blasted with criticism, announced significant program revisions. Local residents sent Sprigle letters, now preserved in the Detre Library and Archives, that underlined the complexity of the issue. Some praised the investigation, others derided it. People found the system’s inconsistencies and enforcement to be the biggest frustrations: why couldn’t one system work for everybody?

As an earlier generation discovered with Prohibition, some American tastes proved difficult to restrain. Consumers wanted meat, especially in heavily industrial districts like Pittsburgh, where workers labored day and night contributing to defense production. Frustrated by inconsistent enforcement and rules they deemed unfair, many otherwise law-abiding people never regarded black market purchases as a serious infringement. (Ultimately, one argument that did seem to work was the threat to public health.)

Black market meat remained a lingering problem in America through October 1946. President Harry Truman finally removed meat from ration roles that fall, fearing that a public grown tired of governmental restrictions would be provoked to further unrest.

Further Reading

The Ray Sprigle Collection, MSS 779, was donated to the Senator John Heinz History Center in 2006 by his daughter Rae Jean Kurland. More about Ray Sprigle can be found in this earlier blog.

Leslie Przybylek, “No Attempt at Concealment”: Ray Sprigle and Pittsburgh’s Black Market Meat Scandal,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (October 2018): 405-408. Available online.

Amy Bentley, Eating for Victory, Food Rationing and the Politics of Domesticity (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998).

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.