On July 3, 1859, abolitionist John Brown first arrived in the vicinity of Harper’s Ferry, Va. (now West Virginia) and rented a farmhouse a few miles outside of town. Months later, on Oct. 16, 1859, he launched his attack on the United States arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, a dramatic but ultimately unsuccessful attempt to ignite an enslaved revolt in Virginia that he hoped would lead to the downfall of slavery across the South. After a promising start, the raid went badly, costing Brown the lives of two sons and eight other raiders. Brown himself was captured and convicted on the charge of “murder, treason, and inciting a slave insurrection.” He was executed on Dec. 2, 1859. (Six co-conspirators were also hanged.)

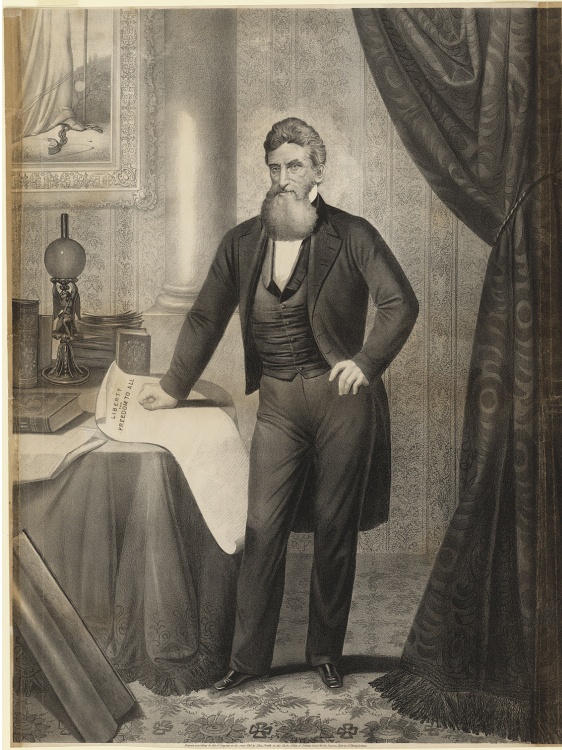

Perhaps more than any other figure connected with abolitionist cause in America, John Brown was a polarizing presence, depicted as demon or martyr depending upon the goals of the artist and the intended audience. An image featured in the new exhibition Smithsonian’s Portraits of Pittsburgh: Works from the National Portrait Gallery emphasizes Brown’s resurrected image after the Civil War, when the Union victory confirmed for many the merits of his purpose even if they disapproved of his methods. The print reminds us that portraits are not neutral images. They are artifacts of a certain time and place, shaped by the motives of creators and sitters and geared to the expectations of specific audiences.

Published in 1866, the posthumous print depicts a respectably dressed John Brown in a richly furnished parlor. Multiple pictorial elements, from the rolled-up map in the lower left corner to the “column of state” behind him and even the suit he is wearing (probably meant to evoke the images from his execution) hint at his well-known deeds, portraying them within the context of the document in his hand, with its inscription “Liberty and Freedom to All.”

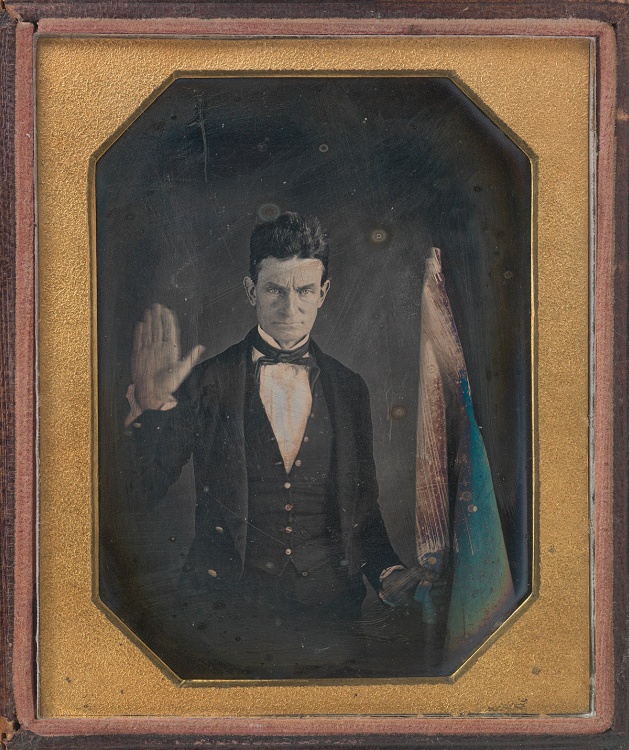

Created by the German immigrant artist Anton Hohenstein and published by Philadelphia lithographer John Smith, the print was designed to appeal commercially to a sympathetic audience that knew how to read and appreciate its details. It conveyed the symbolism of the man and his story—a martyr to a cause—in contrast to more personal likenesses of Brown, such as that captured by African American photographer Augustus Washington around 1846-1847 in a rare daguerreotype also in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Western Pennsylvania knew multiple versions of Brown. Between 1825-1835, residents of the small Crawford County community of New Richmond, Pa., (near Meadville) respected him as a small businessman. Before making national headlines, Brown spent more time there than anywhere else in his life. He operated a tannery that employed 15 people and served as the area’s postmaster. Neighbors appreciated his acts of kindness. Already an abolitionist, Brown envisioned a school for African American children in northwestern Pennsylvania, but he had not yet turned to the violent methods that marked his later activism.

Brown’s Pennsylvania years ended in tragedy. His first wife and a newborn son died within days of each other in 1832. Brown became ill and the tannery failed. As his fortunes disintegrated, neighbors tried to help. But eventually Brown and his family moved to Ohio in 1835, where he suffered further financial losses; he would go bankrupt by 1847. In 1837, after a fellow abolitionist leader was shot and killed by a mob in Illinois, Brown dedicated his life to ending slavery. He became increasingly immersed in the abolitionist cause, especially after 1854, as the Kansas-Nebraska Act ignited the border war confrontations between pro and anti-slavery factions in Kansas and Missouri, a conflict that came to be known as “Bleeding Kansas.” Brown joined his sons in Kansas and became enmeshed in the escalating guerilla conflict. His participation in key events such as the Pottawatomie Massacre paved the way for his vision of the raid at Harper’s Ferry. (You can explore another Western Pennsylvania connection to Bleeding Kansas in this video about the abolitionist rifles carried on the Steamboat Arabia.)

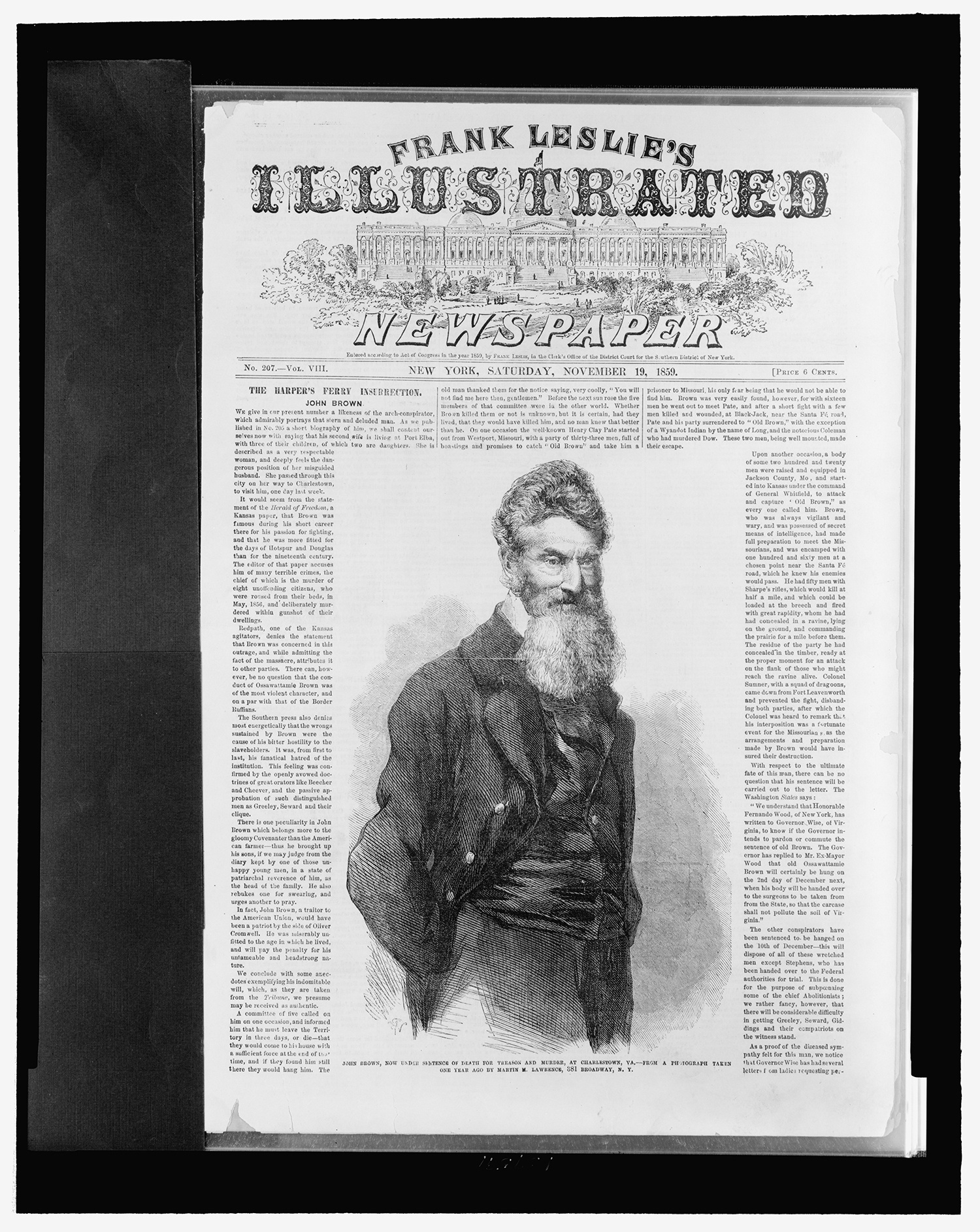

By the time Brown reached Harper’s Ferry on July 3, 1859, many Americans deplored his reputation for violence. After the raid failed and Brown was captured and executed, a majority agreed with the verdict. This included the local press. The Pittsburgh Daily Post noted on Dec. 2, 1859, “Brown has sown the wind, and must reap the whirlwind. The kindling of revolutionary flames must be quenched by the strong arm of the law.”

But there was also strong sentiment in Brown’s favor, including from largely German immigrant populations in cities such as Cincinnati and Milwaukee, people who had fled European upheaval in 1848-1849. Many believed in the abolitionist cause. In both cities, mass meetings of German Associations in December testified to their support of Brown. It is interesting to speculate that the print later made by the German Anton Hohenstein and Smith, published in 1866 in a Pennsylvania city with its own clear German presence, may have especially appealed to this market.

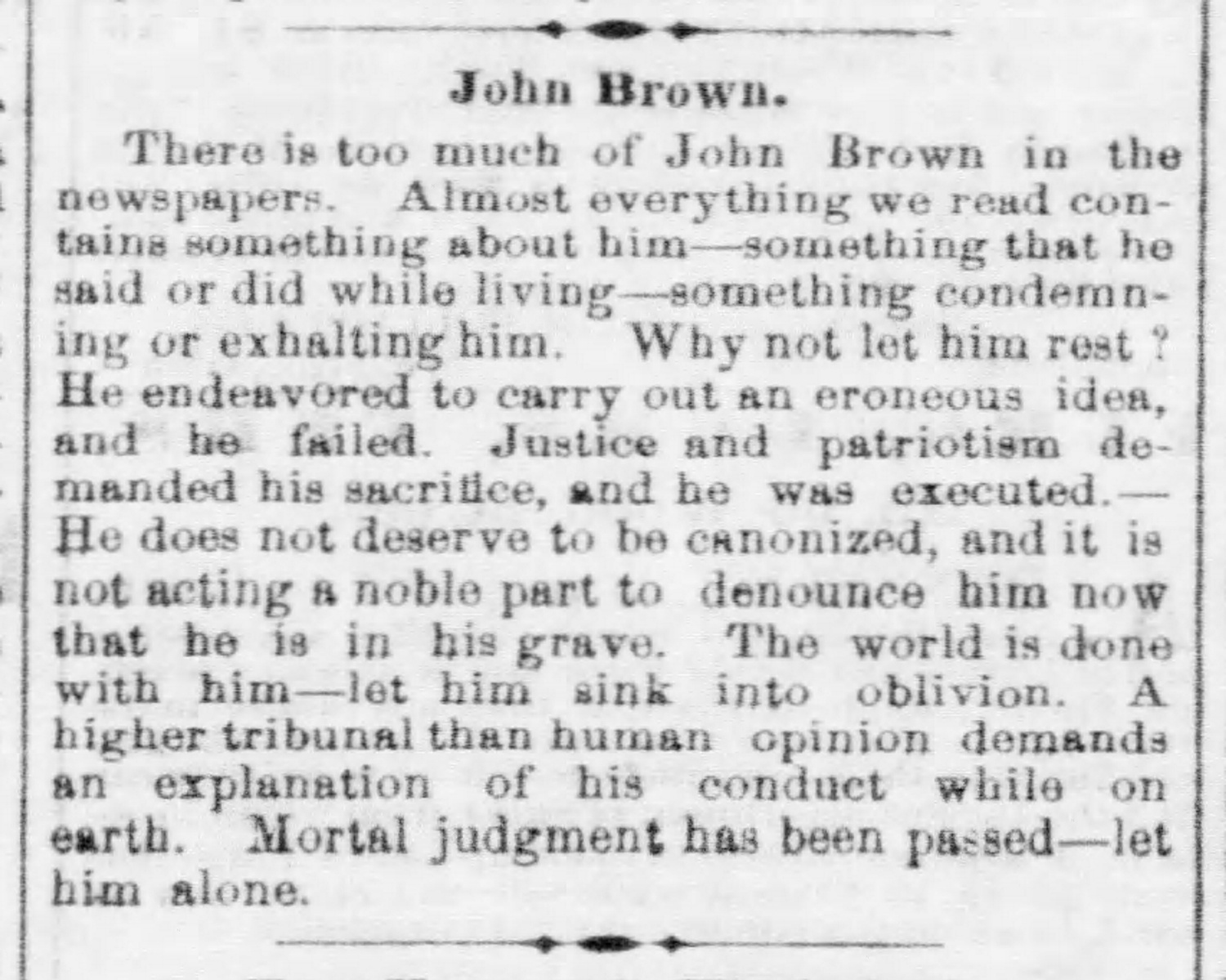

As for Brown, the coverage of his actions and demise dominated the headlines through the end of December 1859. So consistent were these debates that the Pittsburgh Daily Post grew tired of them, exhorting on Dec. 21, 1859: “There is too much of John Brown in the newspapers. . . . The world is done with him—let him sink into oblivion.”

Of course, that did not happen. Brown’s story and image resonated through the decades, as new audiences found relevance in the questions his actions posed. The print issued after the Civil War illustrated one chapter in a record of creative engagement with the one-time Western Pennsylvania tanner that continues into the 21st century. Two new musical works based on Brown’s life, the opera John Brown by American composer Kirke Mecham and the improvised jazz musical John Brown’s Truth by William Crosson, debuted between 2008-2010, part of a flurry of activity related to the 150th anniversary of the raid at Harper’s Ferry. What new vision might be next?

Explore Anton Hohenstein’s print of John Brown currently on display in the exhibition, Smithsonian’s Portraits of Pittsburgh: Works from the National Portrait Gallery, now open at the Senator John Heinz History Center.

Further Reading

Ernest C. Miller, “John Brown’s Ten Years in Northwestern Pennsylvania,” Pennsylvania History 15 (1948): 24-33.

Mischa Honeck, “Abolitionists from the Other Shore: Radical German Immigrants and the Transnational Struggle to End American Slavery,” Amerikastudien / American Studies 56: 2 (2011) 171-196.

“The Portent: John Brown’s Raid in American Memory,” Online exhibition portal from the Virginia Museum of History & Culture (2009-2011).

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center and lead curator on the Smithsonian’s Portraits of Pittsburgh exhibition.