Oh, those tunnels and bridges. Every Pittsburgher knows that the best way to complicate a morning commute or add extra time to your trip home is to factor a tunnel or bridge into the daily drive.

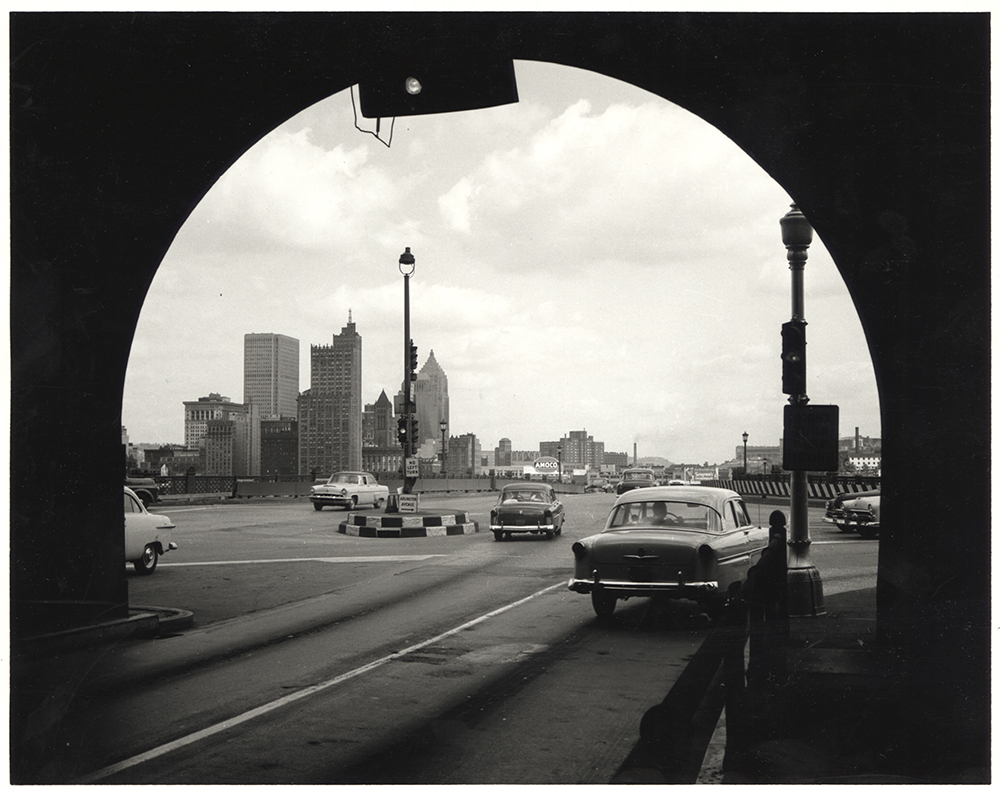

Bemoaning the impact of these traffic passageways is almost a spectator sport. Then something happens, such as the near collapse of the Liberty Bridge last week, and we’re all reminded just how crucial these often-maligned features are to the way people live and work in Pittsburgh today.

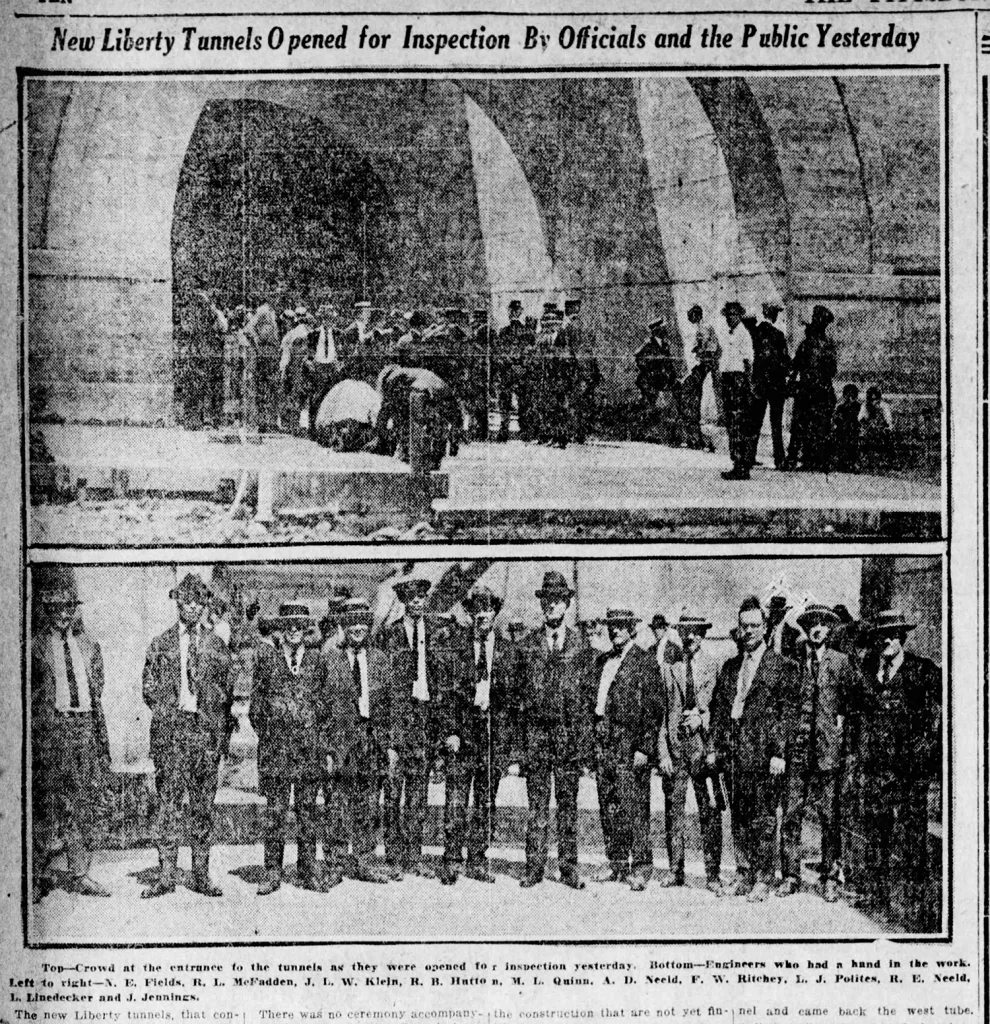

Ninety-three years ago this month, area residents got a chance to see part of that key infrastructure emerge for the first time, when the new Liberty Tunnels opened for public inspection on Sept. 8, 1923.

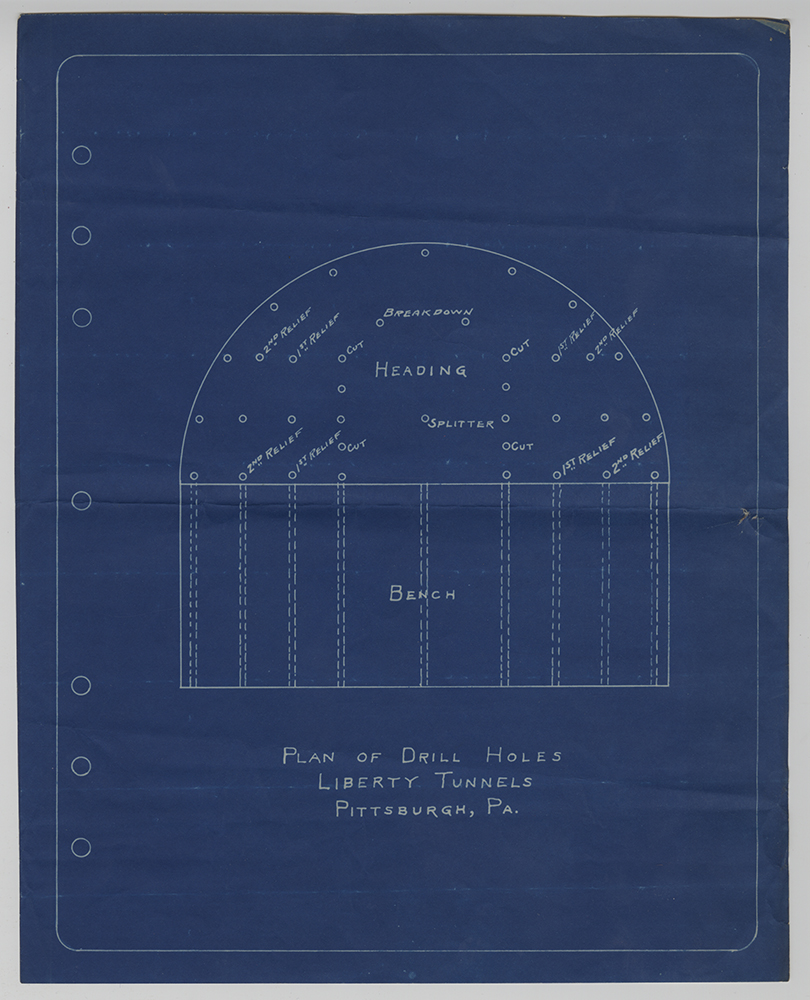

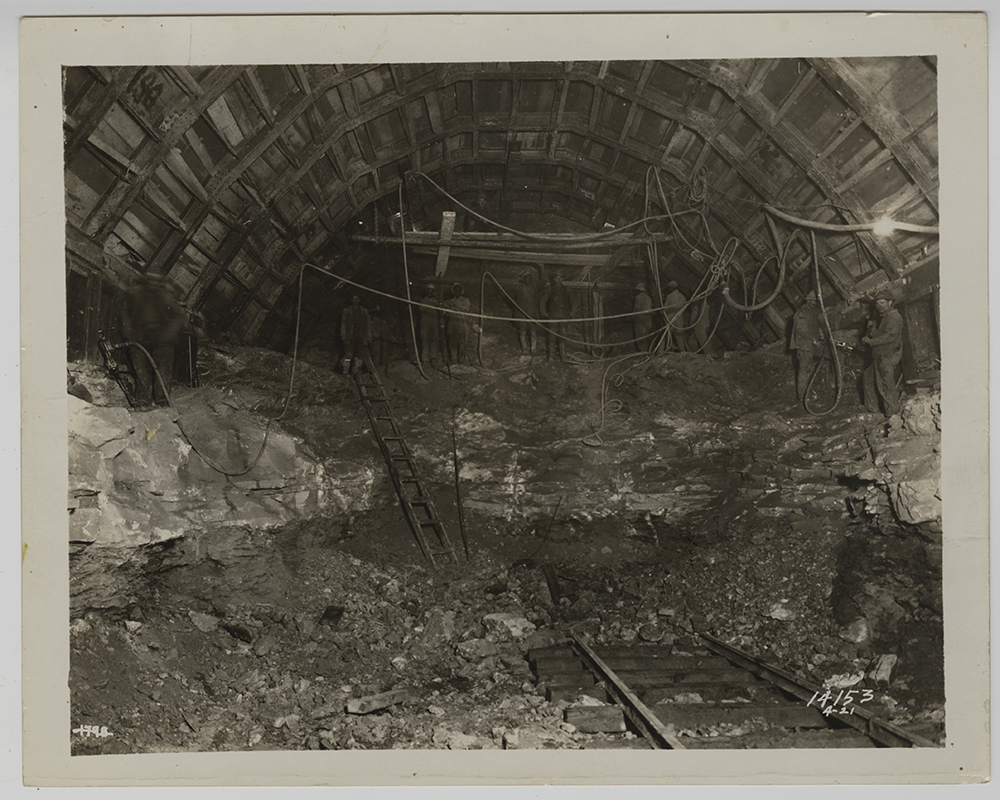

Although the tunnels were still months away from welcoming cars, it’s hard for us to imagine now how monumental this event was at the time. After a groundbreaking in Dec. 1919, Pittsburghers watched over the course of four years as excavation crews blasted, drilled, and carved more than 400,000 tons of dirt and broken rock out of Mount Washington to create what were, at that moment, the two longest concrete traffic tunnels in the world designed for automobiles—5,889 ft. from portal to portal. Although critics had disparaged the tunnel project as “the cave in the hillside,” that cave, now two finished concrete tubes, was an engineering feat that put Pittsburgh on the map—a sign of the Steel City’s modern progress.

Now curious throngs would finally get to see inside those tunnels. According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, crowds gathered long before the appointed time and “marveled at the tremendous achievement.” No ceremony was planned; this wasn’t an official opening. But as project engineers, Allegheny County Commissioners, and city officials gathered to tour, they were beaten to the entry by a small yellow dog, who according to the Pittsburgh Press, ran through the east tunnel ahead of them, becoming the first living creature to make the full trip. A group of boys ran in after the dog and they all came out again. The official tour then proceeded in an orderly manner, entering through the east tunnel and making the round trip to come back out through the western tube.

Controversy over the tunnels would continue to play out over the next few months. Debates about when the Liberty Tubes would open for cars erupted in December when Mr. Clifford Holland, chief engineer for a dramatic new tunnel project in New York City (the soon-to-be named Holland Tunnel, which would displace the Liberty Tubes as the longest auto tunnel in the world), went public in Pittsburgh after another inspection tour, saying that there was no reason that cars were being delayed from entry over fears of ventilation and auto exhaust. This assessment proved to be mistaken on May 10, 1924, when a traffic jam in the now-opened tunnels did, in fact, lead to 12 people being overcome with fumes and panicky motorists seeking ways to flee the tunnel for fresh air.

But that was all in the future. It was only the accomplishment that people saw on that fall day in Sept. 1923 as they walked the full distance in through the east tunnel and back out through the western side. In spite of the tunnel’s first small four-footed visitor, what they saw, clearly, was a sign that Pittsburgh had certainly not “gone to the dogs” and was a city on the rise.

Leslie Przybylek is curator of history at the Heinz History Center.