It’s a January evening in Pittsburgh in 1877. Thirty churches across the city and surrounding suburbs are bursting with people. In some places, the crowds spill onto the streets outside. At the United Presbyterian Church, the aisles are as packed as the pews. Anticipation is in the air. A carriage pulls up outside, and the rider is quickly ushered into the church through a window, since the aisles have been made impassable by the thick crowd. As the man steps inside, applause erupts and excitement courses through the crowd.

This scene depicts the atmosphere of a Francis Murphy gospel temperance meeting, as described by famous Women’s Christian Temperance Union leader Frances Willard. That’s right – in the 1870s, thousands of Pittsburghers were excited about not drinking alcohol. More than that, their unprecedented response to Francis Murphy catapulted him to fame and made the city the headquarters for one of the greatest international temperance movements in history.

So, who was this temperance rock star, and how did he manage to get Pittsburgh stoked for sobriety?

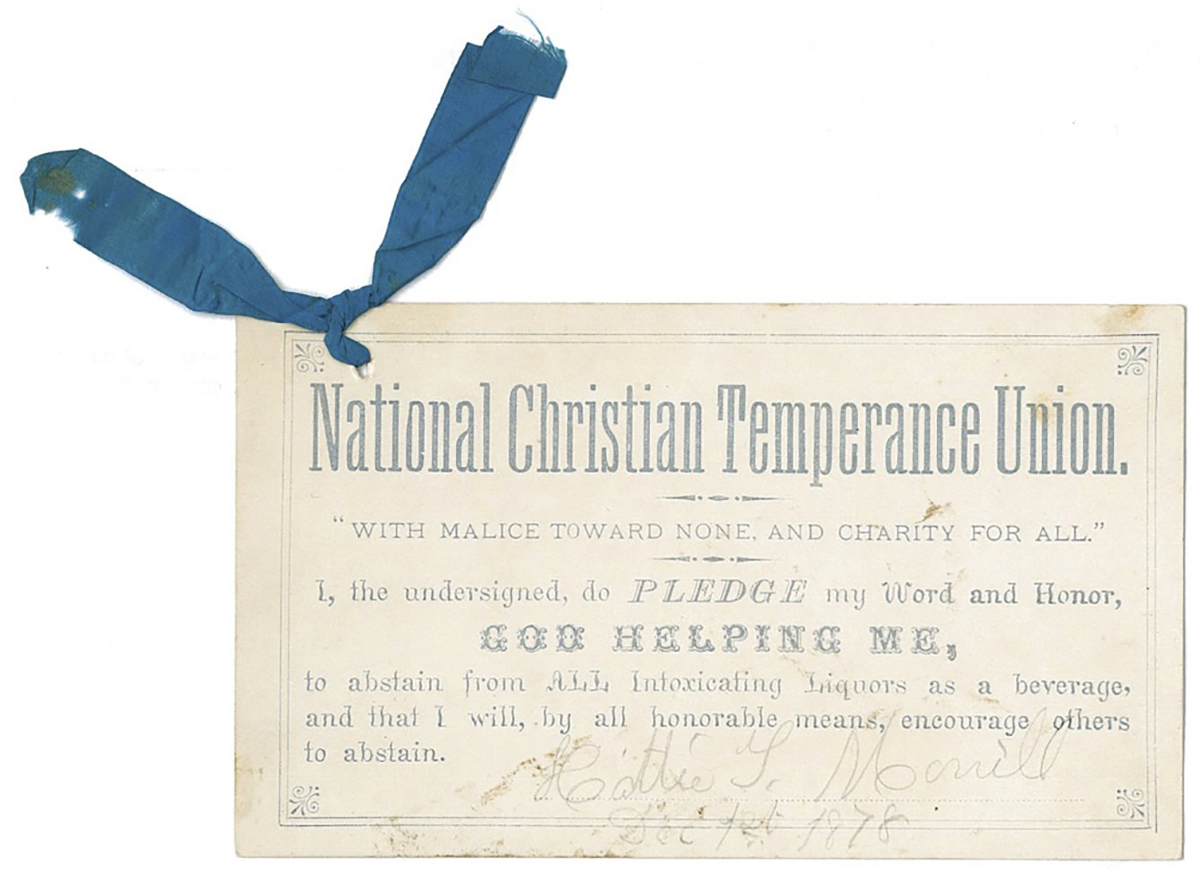

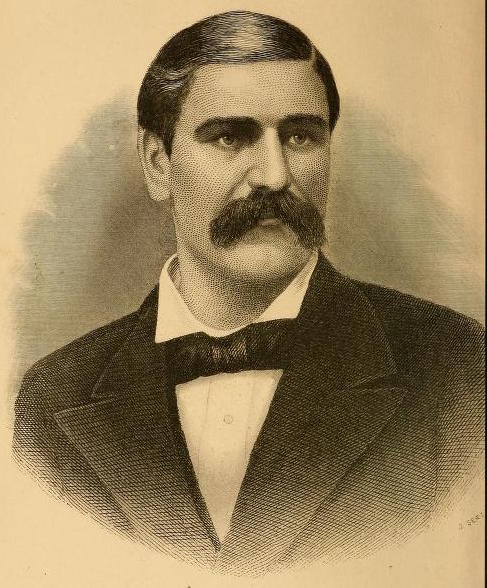

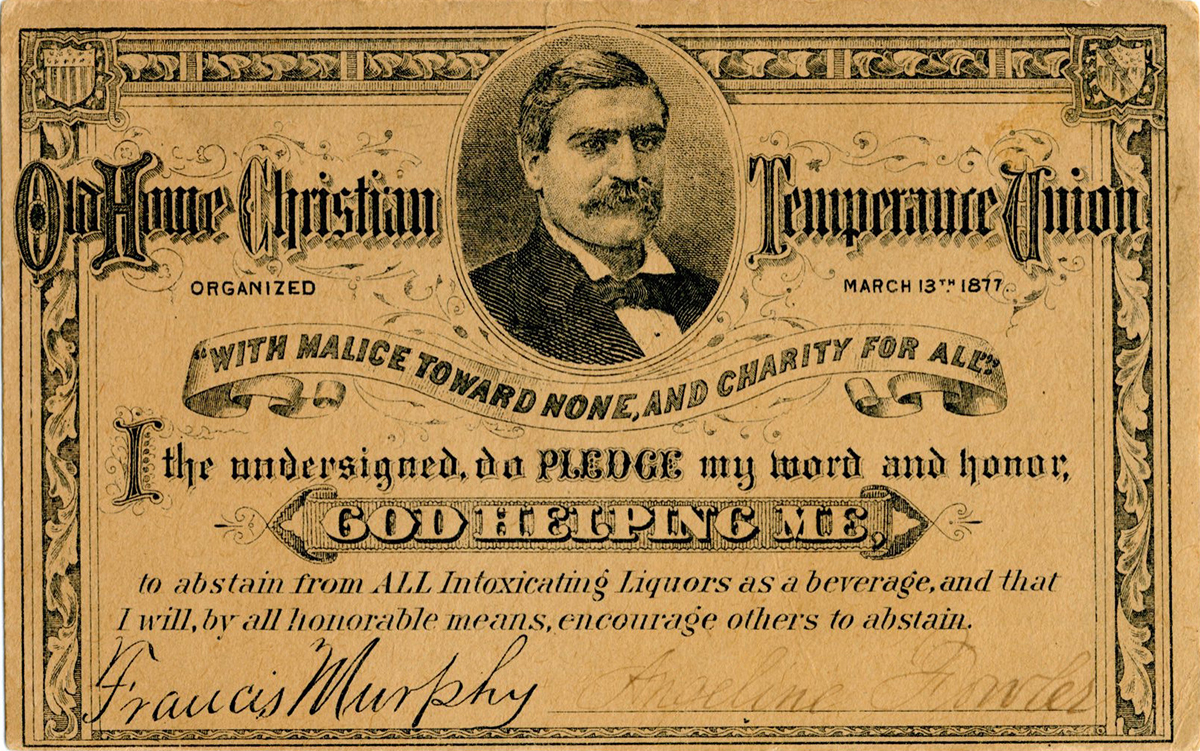

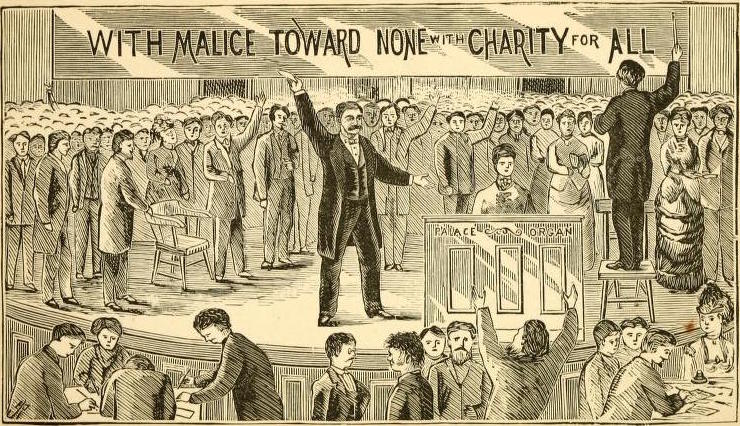

An Irish immigrant, Francis Murphy was a reformed alcoholic whose drinking had destroyed his family and successful hotel and saloon business. Murphy found religion and temperance in 1870 while jailed in Maine for violating the state’s prohibition law. After his release, he spent the next five years telling his story and promoting temperance in New England and the Midwest. Everywhere he traveled, he encouraged people to sign pledges not to drink, which he emblazoned with his motto, “With malice toward none and charity for all.” Murphy advocated “moral suasion” rather than prohibition as the solution to America’s drinking problem, believing the decision not to drink had to be a personal one, not imposed by a legal ban.

By 1876, Murphy had seen moderate success but was far from a household name. Pittsburgh would change that. With the city still recovering from the Panic of 1873 and the saloon business booming, a group of concerned Pittsburghers formed the Young Men’s Temperance Union (YMTU). A few months later, they hired Murphy to deliver eight temperance lectures, hoping he could alleviate the city’s drunkenness and idleness.

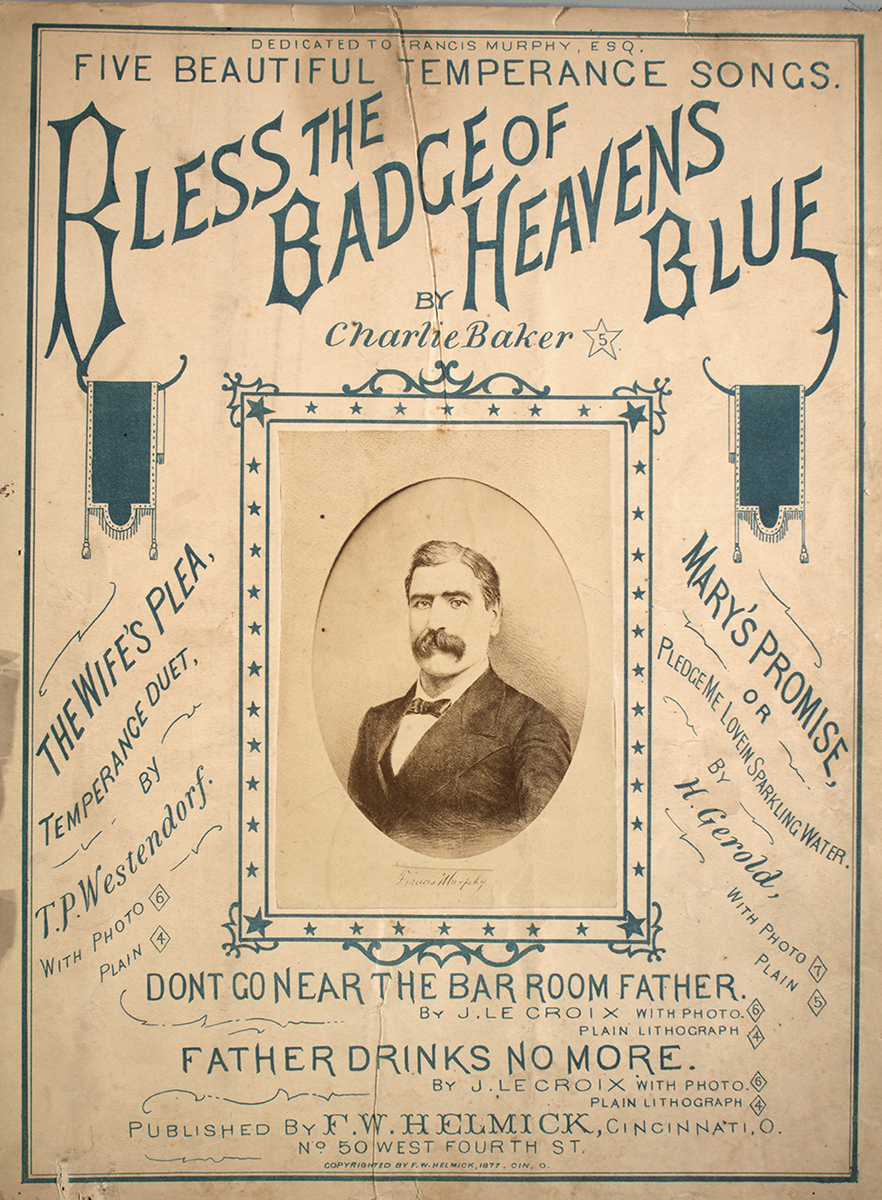

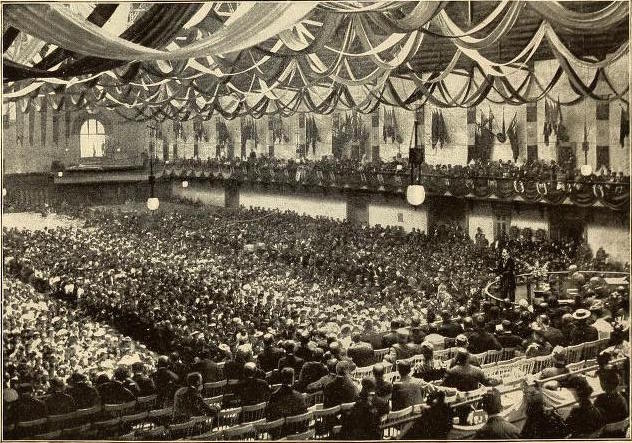

Murphy delivered the first of his lectures on Nov. 26, 1876 to a modest crowd of 8,000 people at the Opera House. The Murphy Movement took off exponentially from there, with thousands more turning out to meetings and signing the “Murphy pledge.” The YMTU extended Murphy’s contract indefinitely. The First Methodist Protestant Church, which once stood on Fifth Avenue, became the movement’s headquarters, with followers affectionately deeming it the “Old Home.” As Frances Willard attested, the scope of the nightly temperance meetings expanded to such a degree that as many as 30 churches in the city and surrounding region held gatherings to accommodate the growing audience. By the time Murphy left the city in late February 1877, the number of saloons had declined, the glassworkers’ union reported a “falling off in the call for whiskey glasses and beer mugs,” and an estimated 60,000 to 80,000 people had signed the pledge and wore a blue ribbon – a new symbol of the Murphy or Blue Ribbon Movement.

Murphy’s geniality and inclusiveness help explain this incredible success, for he was hardly the first or only temperance advocate. Murphy fostered a casual atmosphere at his meetings. In a style very similar to today’s Alcoholics Anonymous, he regularly yielded the floor to testimonials from recovering drinkers, with no regard for class distinction, abilities, or appearance. Devoid of condescension and self-righteousness, Murphy refused to shame drinkers or blame saloons or alcohol producers. He spoke only from his own experience as an impoverished immigrant who struggled with alcoholism. Many in Murphy’s audience found common ground in his fall and hope in his rise. In these ways, Murphy managed to connect with those, particularly the working poor, who did not respond to the typical damning clergy lectures on temperance.

The Murphy Movement was indeed an inclusive one. Meetings were not only attended by men, women, and children, but saw beggars, steelworkers, firemen, and hard-drinking saloonkeepers sharing pews with police chiefs, aldermen, lawyers, stock brokers, and politicians. The Stephen Foster Serenaders, poet Richard Realf, and ardent teetotaler H.J. Heinz were all Murphy supporters.

In addition to his words, Murphy also provided community and social welfare, believing temperance workers “must offer the drinking man something better than he finds in the saloon before we can make any progress.” In Pittsburgh, he organized free holiday dinners for the homeless at the Old Home and raised money to open a shelter for recovering alcoholics. Murphy did so despite church trustees’ objections to the large expenditures and prejudiced complaints that Murphy’s lower class converts broke windows, ruined the carpet, and disordered the pews.

After leaving his headquarters in Pittsburgh in 1877, Murphy launched a campaign that extended the Blue Ribbon Movement to every corner of the nation, as well as Canada, Great Britain, Ireland, and Australia. He received a personal endorsement from President Hayes, and by the time of his death in 1907, Murphy had spoken at an estimated 25,000 meetings, spawned countless temperance organizations, and convinced millions to sign the pledge.

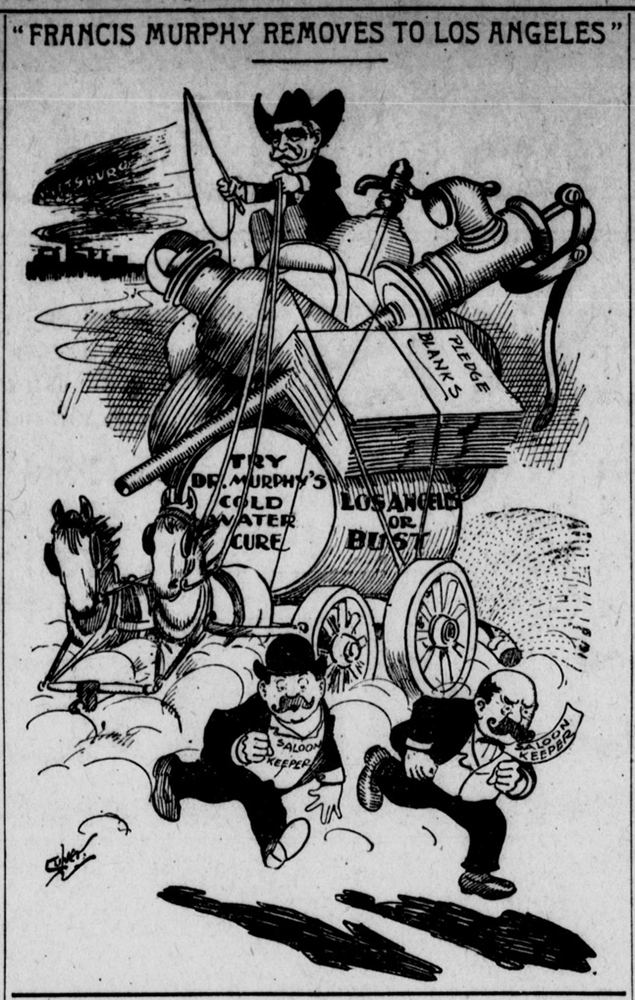

Until he permanently relocated to Los Angeles in 1902, Murphy regularly made his home in Pittsburgh, periodically visiting between travels to celebrate the movement’s anniversaries in the city that had raised him to prominence. However, in Pittsburgh and many other places, it became increasingly challenging to maintain interest and support. The Blue Ribbon Movement’s long-term effectiveness was critiqued, and even Murphy admitted it was difficult to say how many people actually kept their temperance pledges. The failure of this and similar “moral suasion” temperance movements to dry out the nation helped convince many temperance crusaders that prohibition – the very legal ban Murphy had opposed – was the only recourse.

In a way, Prohibition’s subsequent failure vindicated figures like Francis Murphy, who despite their opposition to alcohol, believed in protecting Americans’ freedom to choose.

Sarah Phillips served as a graduate intern with the museum division in the summer of 2017 as part of her coursework with the Cooperstown Graduate Program in Oneonta, N.Y.