Crisp air, fall leaves, and pumpkins everywhere? Halloween must be right around the corner.

Kids rejoice at the upcoming candy bonanza. Retailers celebrate, too, and Halloween is expected to generate more than $8 billion dollars in sales in 2016. That’s a lot of costumes and candy.

It wasn’t always that way. In the mid-1800s, Halloween celebrants pulled up kale or cabbage stalks and heated walnuts in the hearth fire, playing divination games from an earlier age. Halloween was devoted to revealing the identity of a future spouse. That’s why Western Pennsylvanians called it “Nutcrack Night,” while our neighbors in New Jersey and New York still refer to the night of October 30 as “Cabbage Night.” Sound like fun?

Halloween has long been a shape-shifting American holiday, an ever-changing set of regional folk traditions with roots reaching back to the ancient Celts. Images from the History Center’s Detre Library & Archives illustrate how Pittsburgh’s celebration has changed through the years.

A photograph from the Reiber-Sachs Collection captures a Halloween party in Millvale in 1914. The image’s costumed young adults illustrate the masquerade tradition that dominated Pittsburgh celebrations into the 1920s. Similar to a pre-Lenten Mardi Gras, parades, street dances, and neighborhood gatherings included confetti and colored paper streamers that were thrown in mock battles. Crowds gathered downtown and people wandered about in costume. Local police issued stern warnings that “ticklers (a stick used to poke people),” talcum powder, and “flying wedges” would not be tolerated. Of course, there were also children’s parties and activities – Kaufmann’s offered a spooky “Halloween Nook” in 1915. But Halloween was largely an adult affair.

Kids, for better or worse, found ways to amuse themselves. Halloween was a holiday for pranksters. Police warnings hint at the level of mischief that arose, most of it done by kids. Local newspapers in the 1920s and 1930s are filled with reports of soaped cars, streetlights knocked out, fire hydrants turned on, random property damage, hatchets through doors (!!), and objects such as pianos ending up in backyards. Multiple accounts detail frantic drivers reporting a “victim” laying in a busy street such as Saw Mill Run Blvd., only to realize – upon closer glance – that it was really just a dummy. Sometimes “muffled giggles” could be heard in the background.

Nationwide, Halloween became such a dangerous holiday that civic leaders called for solutions. The realization dawned that handing out treats to children might diminish the tricks. In Pittsburgh, communities from Carrick to Swissvale began offering parties and parades filled with prizes and treats for the kiddies; vandalism diminished. World War II also helped. As a new sense of civic duty arose and even pumpkins flashed “V for Victory,” excessive pranking seemed downright unpatriotic.

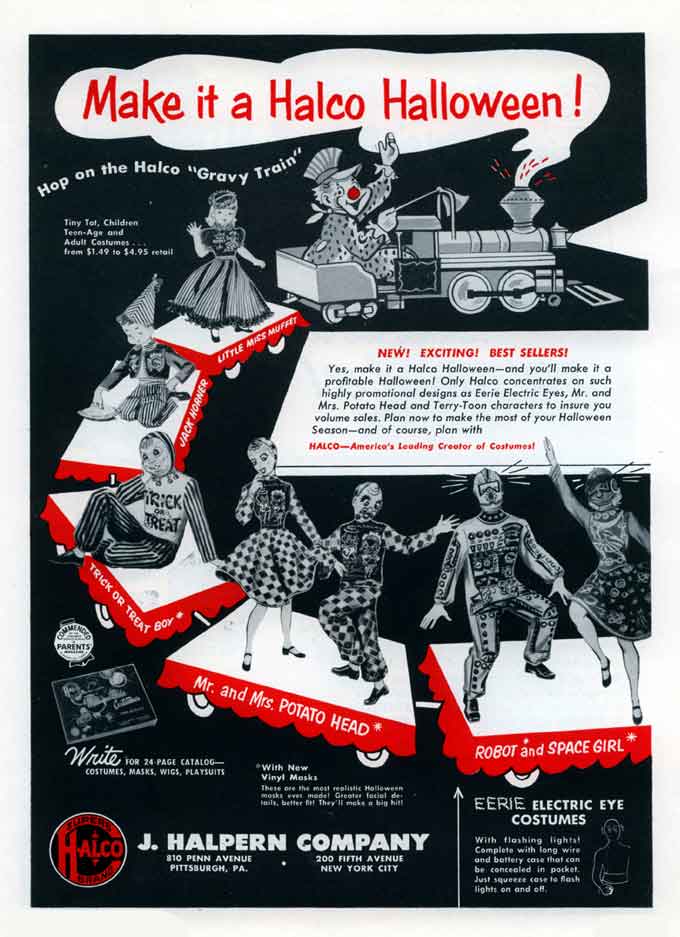

The post-war Baby Boom delivered bigger changes. Halloween became an event for children. Now young masqueraders headed out with candy as their goal, gathered in an evening of “Trick or Treating” perfect for new suburban neighborhoods. From Woolworth’s to Horne’s, stores offered special “costume shops” for children. Local companies such as J. Halpern (Halco brand Halloween masks) and the D. L. Clark Candy Company joined the national manufactures who recognized growing sales opportunities in Halloween. While costumes and characters have changed since then, the 1950s and 1960s created the holiday most of us know today.

But many people missed the spookier side of All Hallows’ Eve. While “haunted house games” had long been a Halloween tradition, the rise of the large commercial scare factories gained steam after 1969, when Disneyland opened their Haunted Mansion. By the mid-1970s, large haunted attractions with professional special effects began to emerge. By the 1990s, amusement parks also got into the act, transforming their grounds into ghoulishly haunted spaces each fall. Here, Etna’s Scarehouse started in 1991 while Kennywood instituted its first Phantom Fright Nights in 2002. Increasingly, adults got back into the spirit of the holiday, turning Halloween into today’s multi-billion dollar industry.

What might those early practitioners of kale-pulling and “Nutcrack Night” think if they saw all of this today? What are your favorite memories of Halloween in Pittsburgh or Western Pennsylvania?

For Further Reading

- Emily Chertoff, “A Sinister History of Halloween Pranks”, The Atlantic, October 31, 2012.

- Chris Heller, “A Brief History of the Haunted House”, Smithsonian Magazine, October 28, 2015.

- Annabelle Smith, “The Halloween Tradition Best Left Dead: Kale as Matchmaker”, Smithsonian Magazine, October 30, 2012.

- Jack Santino, “Halloween, The Fantasy and Folklore of All Hallows”, The American Folklife Center. Library of Congress.

Leslie Przybylek is curator of history at the Heinz History Center.