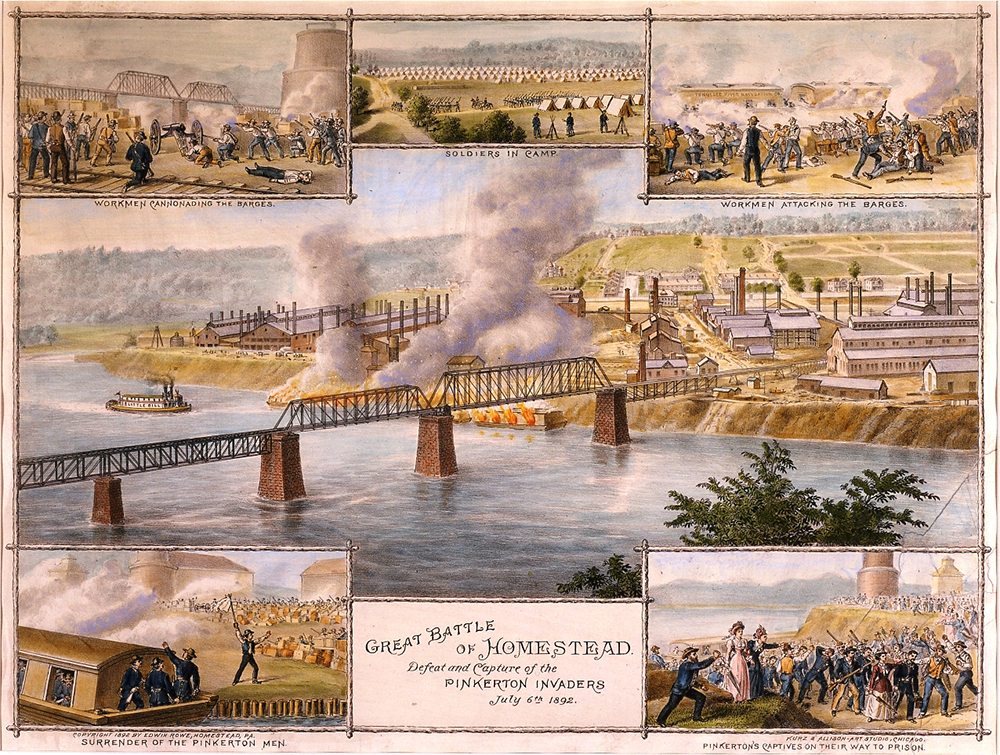

A lithograph in the History Center’s collection provides an interesting perspective on the unfolding of events in the steel strike on July 6, 1892. In title and in imagery it makes clear the viewpoint of the artist. Titled, Great Battle of Homestead, Defeat & Capture of the Pinkerton Invaders July 6th 1892 it features a large central image surrounded by five smaller vignettes. The center panel provides a birds-eye view of the Homestead Mill from across the river, looking down from the hill that rises above the Monongahela on the Squirrel Hill side. The river is in the foreground, the mill stretches out on a great flat plain of ground behind it. Smoke and flames pour out of a barge docked on the mill side, billowing over the railroad bridge and obscuring a section of the mill. No people are visible.

The four small vignettes at each corner of the print document the battle referred to in the title of the image, and detail the events of July 6th from the workers’ perspective. The top corners show workers in battle, using cannon and gun fire against the barges full of Pinkerton men. The bottom left corner illustrates the “Surrender of the Pinkerton Men,” while the bottom right has the “Pinkerton’s Captives on Their Way to Prison.” As a whole, the imagery depicts the violent interaction between the striking workers and the Pinkertons sent by Henry Clay Frick to liberate the mill, as a triumph for the working man. The smaller vignettes recall, as art historian Rina Youngner has noted, Civil War battle imagery and photography. They show organized lines of engagement and depict the workers as soldiers protecting their mill from the invading Pinkertons. The visual narrative captures one of the final times that steel workers would exercise power over their place of work until the federal government supported unionization in the 1930s.

The print is interesting, not just for the seminal moment that it captures and preserves, but also because of who created the piece, Edwin Rowe. Born in Cornwall, England in 1834, Rowe lived with his parents for at least a decade in Wales, where he and his father John are listed as iron ore miners. He marries in 1855 and he and his wife Catherine come to the United States in 1870. By 1880, they are living in Beaver Township, Clarion County where Edwin works as a coal miner. His household includes his wife, his six children ranging in age from Thomas at 28 to Sarah age 6, and his 75-year old father, John. Two of Edwin’s sons, Thomas and Edwin Jr., who is 16 in 1880, also work as “coal diggers.” Within four years the family has relocated to Homestead, as Edwin and Catherine are listed as founding members of the First Baptist Church, which opens there in 1884. Edwin Jr. marries in 1890 and takes a job in the Homestead Works. He is on the factory floor of Open Hearth No. 2 working as a laborer in May of 1892. Paid just $45.35 for his 27 days of labor that month, about $1.68 a day, Edwin Jr. witnessed the rising tensions as the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers and Andrew Carnegie disagreed on the issue of wages. By June, Frick had closed the mill and the stage had been set for the battle of July 6th.

Little is known about Edwin Rowe Sr.’s life at the time of the strike. A city directory entry from 1898 lists him working in a picture and frame store in Pittsburgh, later entries and census descriptions document the same. Clearly Rowe is familiar with military and battle art – he frames the workers in ways that emphasize the individual as heroic actor within the larger collective occupied at war. Intended for a sympathetic audience, one of these prints hung in the hall of the United Steelworkers Local 1397 in Homestead, Rowe’s work becomes a visual narrative that ennobles the worker’s cause. In this telling of the story of the strike, the workers battle for their rights, taking a literal stand on the grounds of the changing industrial landscape, as they fight to retain a voice in the negotiations over their future.

Created as the technology of open hearth steel eclipsed the world of hand forged iron, Rowe’s print captures working men caught between the past, where they maintained some power on the factory floor, and an uncertain future. It is a remarkable visual statement of the changing world of work in the region and reminds us what was truly at stake in Homestead 125 years ago.

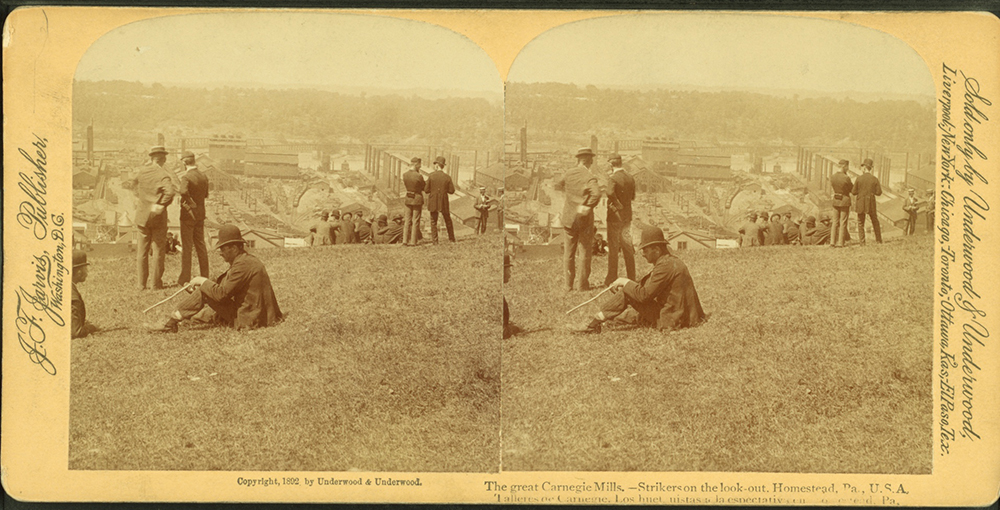

The strikers kept watch of the mill, expecting Carnegie and Frick to send strike breakers or the militia. Courtesy of The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection. The New York Public Library.

For Further Reading

Rina Youngner, “A Working Class Image of the Battle,” in The River Ran Red: Homestead 1892, by David Demarest and Fannia Weingartner, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992.

The Battle for Homestead, 1880-1892: Politics, Culture, and Steel (Pittsburgh Series in Social & Labor History), by Paul Krause, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992.

Anne Madarasz is the Director of the Curatorial Division, Chief Historian, & Director of the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum.