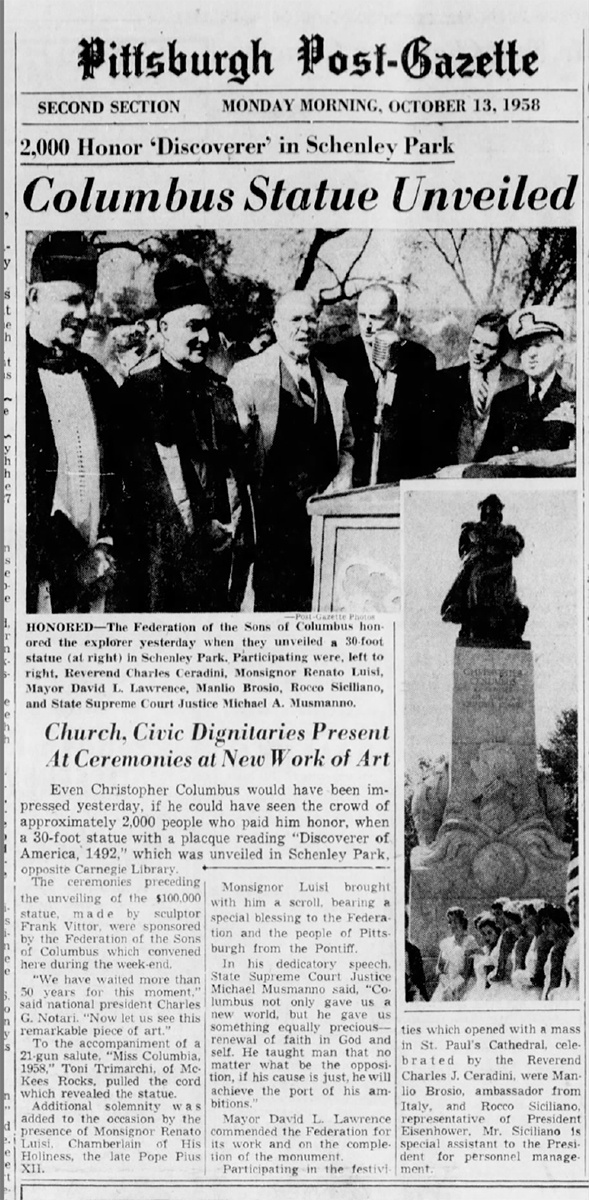

On Oct. 12, 1958, a monument of explorer Christopher Columbus was unveiled to the public in Pittsburgh’s Schenley Park. This event marked the first of many bicentennial festivities celebrating the city’s 1758 founding when a twenty-something George Washington helped establish Fort Pitt.

The dedication ceremony was attended by 2,000 people, including top leaders from the local Italian American community, the City of Pittsburgh, the Catholic church (the Diocese and the Vatican), diplomats representing Italy and the United States, and the artist, famed Italian sculptor Frank Vittor. According to newspaper accounts, orators remarked that the statue represented faith and courage for the community.

Fast forward more than 60 years later – our society is engaged in debates about symbols in America, their meaning and public display. Symbols are subjective and their interpretation can be influenced by personal experience. Symbols are especially complicated when they are made in the image of a historical figure. Columbus is one such case. Is it possible to both publicly laud and protest the same person? This is where we find ourselves today. But how did we get here?

If you are a product of the American public-school system as I am, your education in U.S. history began with Christopher Columbus and the Age of Exploration in the late 15th century. Why do we begin our country’s narrative in this historical moment? Why not begin with Jamestown in 1607 or the landing of Pilgrims in 1620? Why turn the clock back to 1492 and start more than 100 years before the first permanent European settlement in the continental U.S.? The answer lies in the founding of our nation in the late 18th century.

Long before the Italian American community aligned itself with the “Great Discoverer,” our country’s leaders used the narrative of Christopher Columbus to teach ideas of American patriotism. Similar to figures such as George Washington, Columbus’s origin story appealed to early Americans who were in the process of constructing a national identity: he wasn’t of noble birth; he did not sail on behalf of the British crown; and his success was attributed to his talents and effort. This is when Columbus first enters the American consciousness as a symbol and, with this action, is embedded in our nation’s history.

A little more than 100 years later, another shift occurs in Columbus’s legacy in America. In the early 1880s, immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe entered the U.S. in increasingly large numbers. This population shift upset some Americans; unlike previous waves of immigrants, the customs, languages, and religions practiced by these foreign-born groups stoked Nativist sentiments.

Discrimination experienced by non-Anglo-Saxon, non-Protestant immigrants led to intolerance in many communities. One event, in particular, got the attention of the American government and the Italian government. On March 14, 1891, a mob of vigilantes murdered 11 Italian men in a New Orleans prison after they were acquitted of shooting the city’s chief of police (18 men and a 14-year-old boy were originally arrested for the crime). And, while the tragedy in New Orleans seems unconnected to the veneration of Columbus, the diplomatic solution was, in part, for American leaders to exalt a figure of Italian heritage to assuage Italy’s anger (for more on this history, see the analysis done by sociologist Charles Seguin and doctoral student Sabrina Nardin on the impact of protests initiated by the Italian government in the wake of the New Orleans lynching).

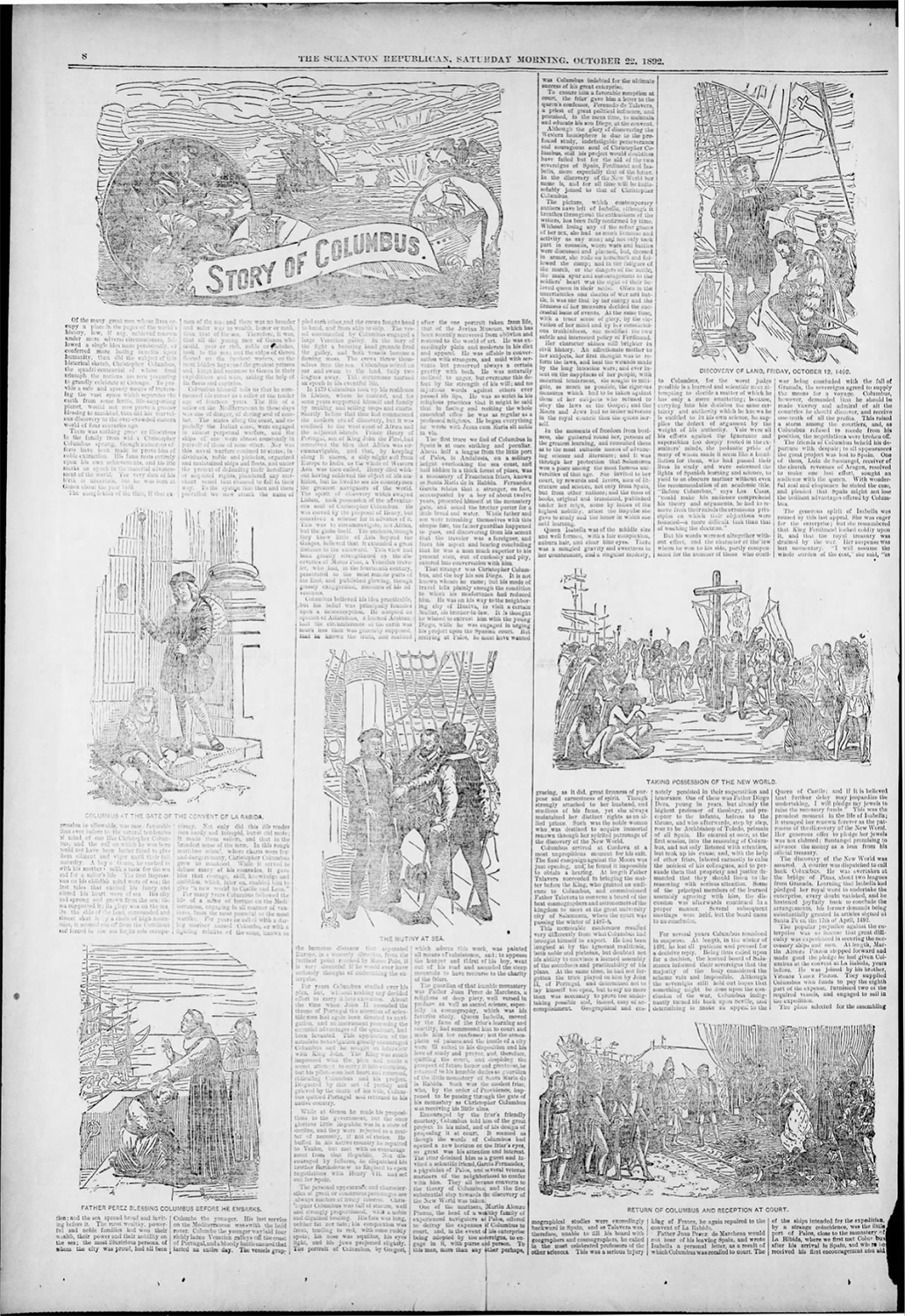

A year and a half later, in 1892, the nation embarked on a very public national embrace of the navigator for the 400th anniversary of his landing in San Salvador. His accounts were trumpeted louder than ever before: his life was published in full-page spreads in newspapers across the nation, churches and synagogues held services, and public-school students participated in patriotic exercises.

The activities acknowledging Columbus were steeped in American symbols – flags, Uncle Sam, and red, white, and blue bunting. There wasn’t a celebration of this magnitude in 1792 for Columbus’s 300th anniversary. What had changed in 100 years, and what did this effort to celebrate “Discoverer’s Day” achieve?

Consider this statement made by U.S. Congressman Benjamin Franklin Meyers in Harrisburg, “If Christopher Columbus had been an American, native and to the manner born, his career could not have illustrated more singularly the character of a self-made man risen to greatness and honor through his own unaided efforts. Notwithstanding his foreign birth, and his fealty to monarchial institutions, his whole life is a lesson that may be studied with profit by the youth of our country.” Meyers’ statement, which echoed the sentiments of other politicians, was made at a time when America’s foreign-born population had risen to 15 percent. Columbus was offered as an American hero that both old stock Americans and foreigners of all classes could admire, emulate, and heroicize.

The national overhaul of Columbus was successful. From 1892 forward, the Italian American community embraced the explorer and celebrated him annually in October with beneficial societies, small businesses, and community stakeholders taking the lead. By the mid-20th century, Columbus celebrations were synonymous with celebrations of Italian pride as well as American patriotism. Given the demographics of Pittsburgh, it’s natural that veneration of Columbus took root as the community looked for ways to show native-born citizens they were “good Americans.” Demonstrations of loyalty to the adopted homeland were important to the Italian American community and, in part, explain how Columbus’s image became monumentalized in the U.S. But, what’s the story with the statue in Pittsburgh? Most importantly, what does it mean? To understand, one must consider who made it and why.

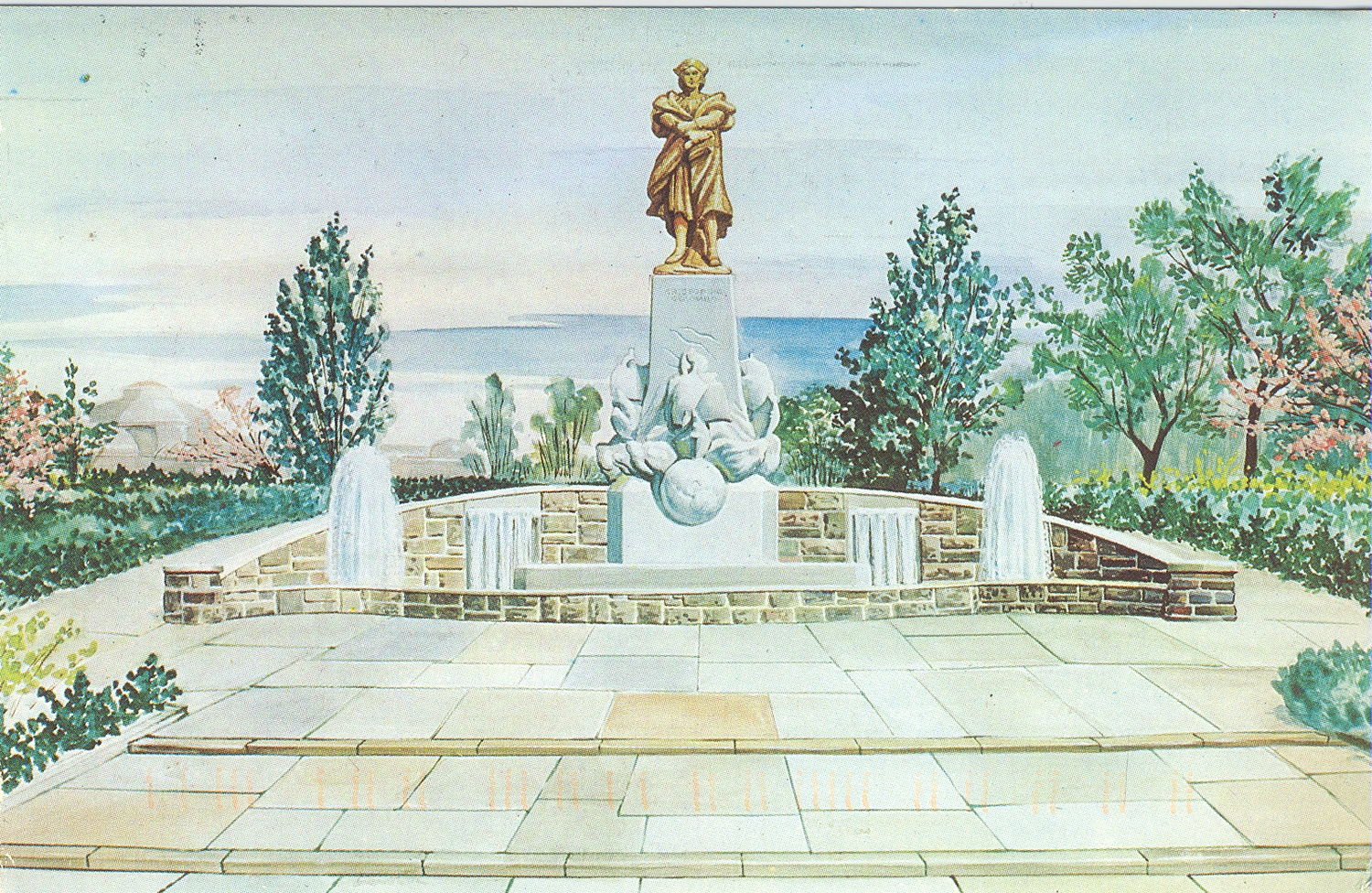

The statue was gifted to the city by the Columbus Monument Committee, a group sponsored by the Sons of Columbus of America, in a multi-year process where the organization fundraised for the creation of the statue, acquired the plot in Schenley Park, and participated in the democratic process of approval through the city of Pittsburgh’s Art Commission and Public Works Department. It was vetted as all public art is in the City of Pittsburgh. The only public criticism at the time was a letter to the editor complaining that the $100,000 raised for the monument could have been used for other civics projects. Based on the few surviving documents related to the monument’s creation (which reside in the Heinz History Center’s Detre Library & Archives), it’s clear the committee believed they were giving something back to their community.

In 1965, landmark immigration legislation, known as the Hart-Cellars Act, opened our country to new migrants, expanding our nation’s foreign-born populace once again. For many in the Italian American community, the passing of this legislation, which eliminated the racist quota system, was the final barrier to acceptance into mainstream American society. In the following decade, Americans of all backgrounds embraced their racial and ethnic heritage in displays of pride. For Italian Americans, it’s fair to say that after more than a century of trying to find our place in this great nation, we’ve succeeded – our patriotism is no longer in question; we hold positions of power in government, business, and industry; slurs for our ethnic group have fallen out of everyday use; we did what our ancestors dreamed of. But, what about our fellow citizens, our peers, our neighbors, and our friends? Do Pittsburghers of all backgrounds feel the same confidence with their status in America? And what does this have to do with Columbus?

Just prior to the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s landing in 1992, historians began to reevaluate the legacy of Columbus in light of the impact his voyages had on indigenous communities in the Americas. For centuries, we focused on the explorer narrative part of Columbus’s record. At the end of the 20th century, historians and American Indian activists helped us learn more about the full picture – yes, he was still a great navigator, but he was a poor administrator and, by his hand or not, atrocities were committed in his name. He opened the door for Conquistadors and the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, both of which devastated populations, destroying languages, customs, and culture. This part of the history upsets many Americans (as it rightfully should) and it has angered some to the point of vandalism and forced removal, actions that go beyond our right to protest, the freedom of assembly, and the freedom of speech. As citizens, we have laws that protect our ability to petition our government, and vandalism disregards the part of our democratic process where we debate and discuss controversial issues before passing a judgement.

Our country’s political ideology is based on a system that allows for progress, refinement, and, most importantly, a voice for the people; like our laws, our symbols and their public display can be brought into a process of consideration. The people of the United States have pushed our great experiment of democracy forward for nearly 250 years, an incredible feat when one considers we are working with documents crafted at the end of the 18th century. No matter how far forward we move on the timeline, we must remember to go back to foundation to inspire wise actions for the future. This is a challenging moment in our history, and we will debate anytime the public takes umbrage with the symbols we have inherited from previous generations.

Here in Pittsburgh, we are fortunate there is a process laid out by the city’s Art Commission where we can exercise our civic duty and share our concerns with the commissioners. If we can move forward with open hearts and respect, we will surely find common ground, allowing us to work together to find a solution.

As for the History Center’s Italian American Program, we continue to document all sides of the Columbus story: the background of the statue, and the veneration and the vilification of the historical figure. The History Center’s collection includes the model of the monument made by artist Frank Vittor and the archives from the 1950s related to the statue’s creation and dedication. Our resources are available to the public. We will continue to field questions from the community, directing them to relevant collections, articles, and books. Our mission is to not only preserve the past, but provide interpretation so future generations may understand what has happened and how it impacts us today.

This video from our archives shows a Columbus Day Parade in Pittsburgh, Pa. in 1939. Please note that this video has no sound.

From the Sons of Columbus of America Records and Photographs, MSS 904, Detre Library & Archives at the Heinz History Center.

Melissa E. Marinaro is the director of the Italian American Program at the Senator John Heinz History Center.