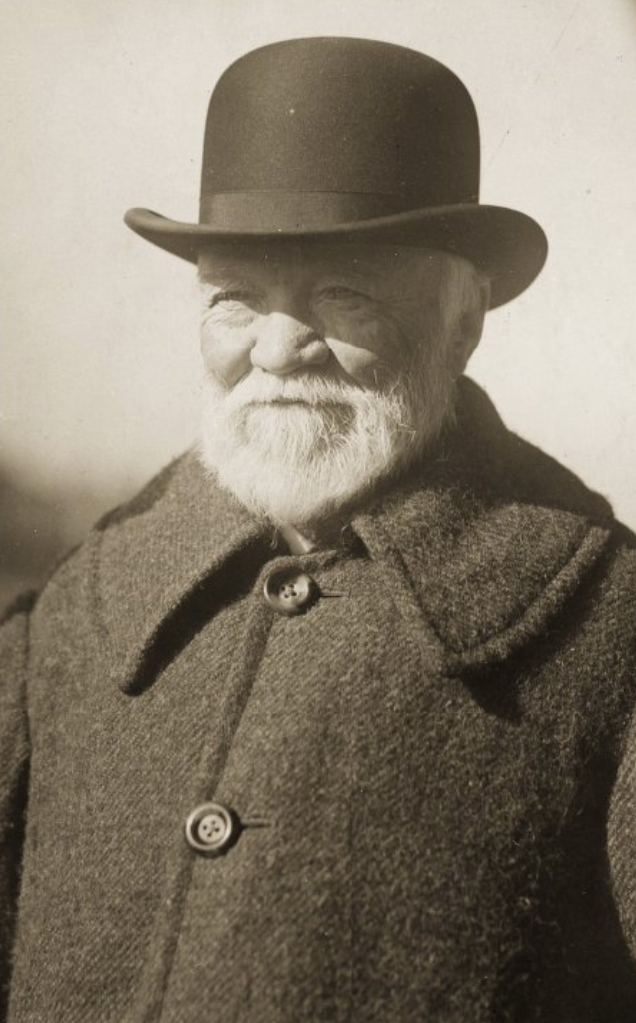

It is a little-known fact that Andrew Carnegie, Pittsburgh’s industry tycoon, was a champion of simplifying English spelling.

In fact, Carnegie saw spelling reform as a means of achieving world peace.[1] He thought that if English could be simplified and standardized across different dialects, English speakers might be drawn closer together. He also saw the potential for English to be a world language. Carnegie believed that sharing a common language gave people a sense of kinship conducive to peace, a belief he expressed in his essay, “Does America Hate England?”:

The strongest sentiment in man, the real motive which at the crisis determines his action in international affairs, is racial. Upon this tree grow the one language, one religion, one literature, and one law which bind men together and make them brothers in time of need as against men of other races.[2]

Although Carnegie may have had a bit of a personal motive for supporting spelling reform — he was notorious for bad spelling[3] — it appears that his main motive was world peace. Only time would tell whether his plan would work.

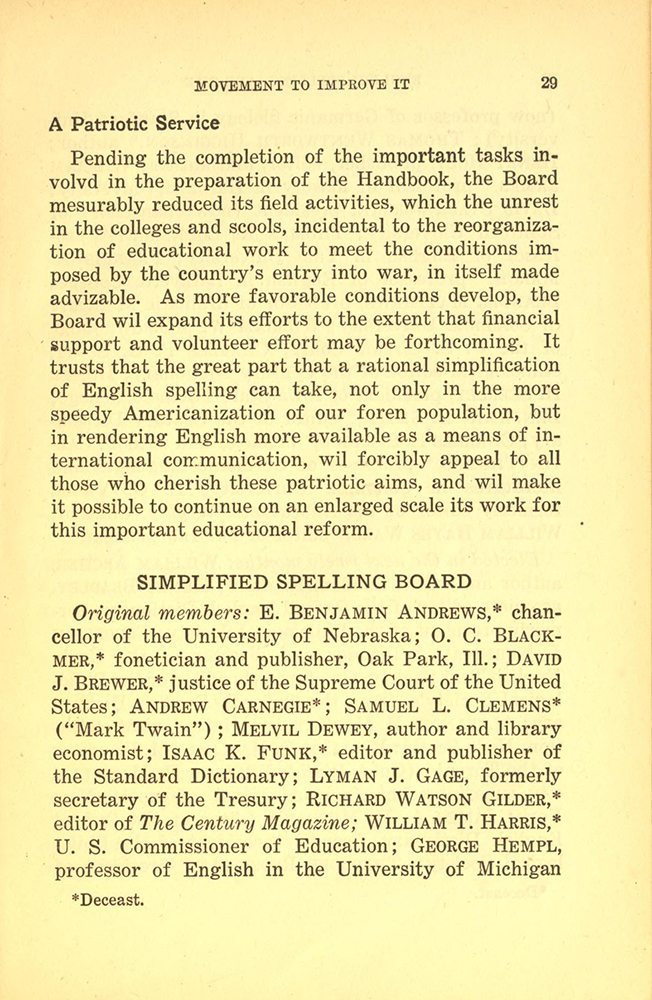

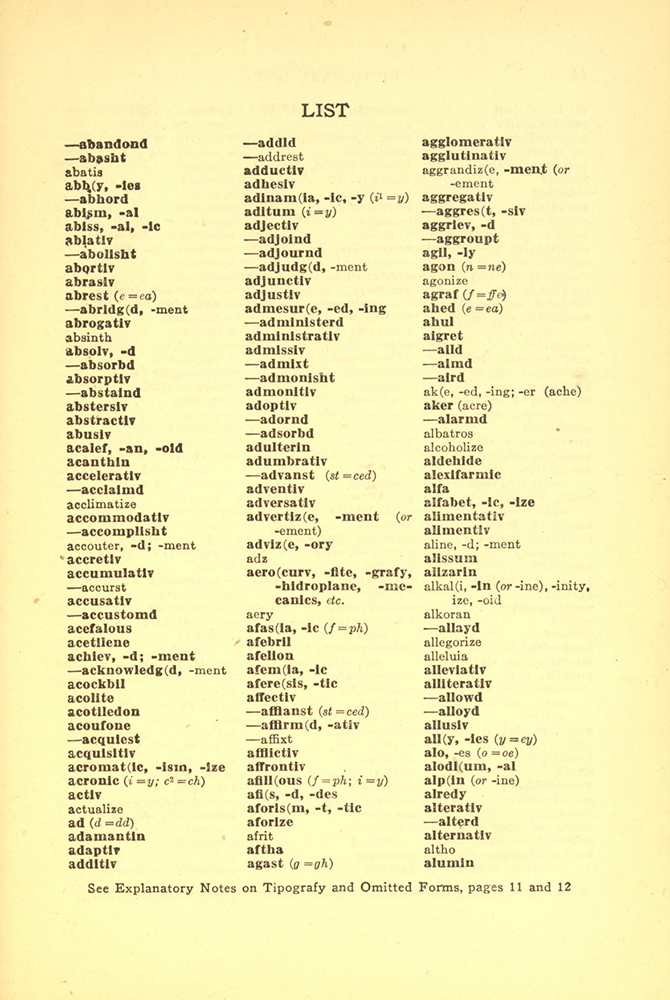

In 1906, Carnegie donated $250,000, a fortune at the time, to establish the Simplified Spelling Board.[4] According to the “Handbook of Simplified Spelling,” published by the Board in 1920, its purpose was to promote public interest in the disordered state of the English language and facilitate spelling reform.[5] With that intention, the entire “Handbook” was written with the reformed spellings promulgated by the Board; the effect is jarring, to say the least. The Board lobbied for the alteration of about 300 words in an attempt to standardize English spelling and make it more predictable.[6]

Carnegie’s role on the Simplified Spelling Board was not merely financial. He himself signed a pledge to use all of the new spellings, a pledge that he kept for the rest of his life.[7] A true activist for reform, Carnegie communicated with influential figures such as writers, newspaper editors, and even President Theodore Roosevelt, always collecting pledges to use the new spellings. But even with all the support Carnegie attracted, the changes never gained mainstream acceptance. For better or for worse, the movement for spelling reform was losing steam by 1920 when the “Handbook” was published. Carnegie had stopped funding the Board in 1915, frustrated by its lack of progress.[8] In the end, only a few of the spelling reforms survived, including judgment instead of judgement and medieval instead of mediaeval.[9]

Andrew Carnegie was not the first or the last person to try to simplify the English language. As early as 1768, only about a century after English spelling was standardized, Benjamin Franklin called for spelling reform; he warned that English words would become like Chinese pictographs if spelling was not changed to reflect punctuation.[10] Noah Webster, the famous lexicographer, urged Congress to make simplified spelling a legal requirement and tried to reform spelling himself (albeit inconsistently) in his many works.[11] Subsequent to Carnegie’s effort, at least three simplified versions of English have been proposed,[12] and yet all attempts appear to be futile.

English is a living language, entrenched in and controlled by a mass culture, and not even multimillionaire Andrew Carnegie could change it.

[1] David Nasaw, Andrew Carnegie (New York: Penguin, 2006), 664.

[2] Andrew Carnegie, “Does America Hate England?” in The Gospel of Wealth and Other Timely Essays (New York: Century, 1900), 252.

[3] Nasaw, Andrew Carnegie, 664.

[4] Bill Bryson, The Mother Tongue: English and How it Got That Way (New York: Perennial, 1990), 130.

[5] Henry Gallup Paine, Handbook of Simplified Spelling (New York: 1920), 16.

[6] Richard E Hodges, “A Short History of Spelling Reform in the United States,” The Phi Delta Kappan 45, no. 7 (1964): 332, www.jstor.org/stable/20343148.

[7] Joseph Frazier Wall, Andrew Carnegie (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1989), 893.

8 Ibid.

[9] Hodges, “A Short History,” 332.

[10] Bryson, Mother Tongue, 127, 129.

[11] Ibid., 129, 155-157.

[12] Ibid., 191-193.

Julia Snyder is the summer 2018 intern in the Publications department at the History Center.