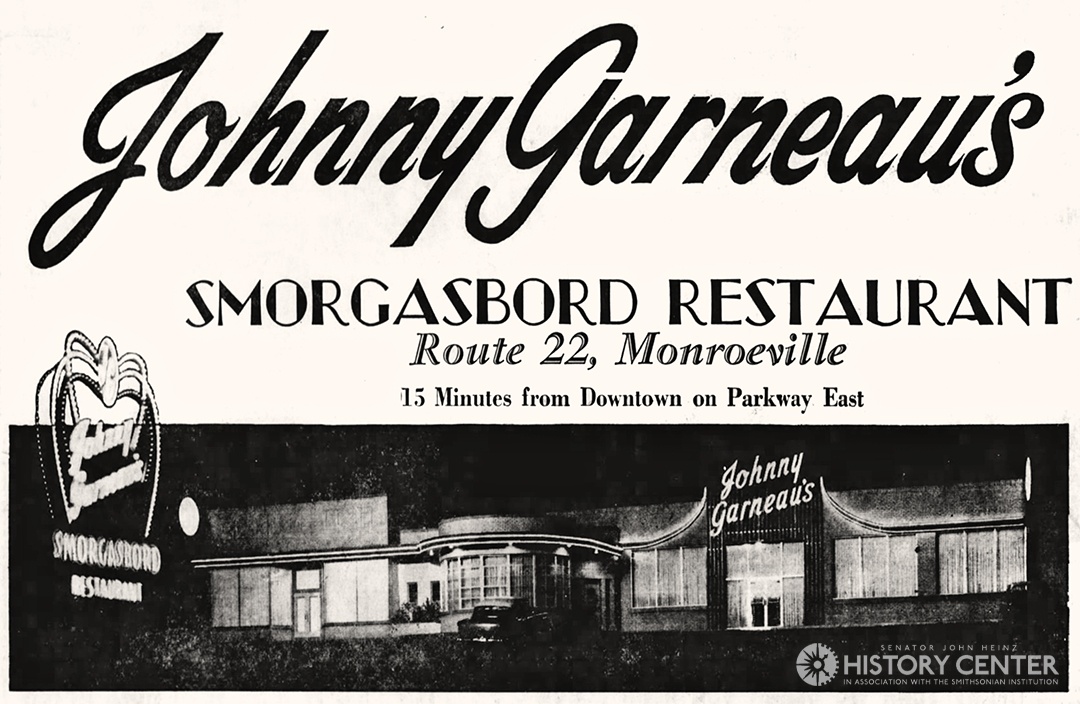

If you grew up in Western Pennsylvania from the 1950s to ’80s, Johnny Garneau’s Smorgasbords were the name in buffet restaurants. The challenge—then and now—is that customers can be careless with good hygiene around all that food. More than 60 years ago, Garneau took a big step to resolve that when he patented a sneeze guard, the angled plate of glass or plexiglass that shields your food from others’ airborne germs.

Garneau entered the restaurant business in 1949 with the tiny Beanery in Clarion, 80 miles northeast of Pittsburgh.1 He launched his first smorgasbord there in 1952, when the idea from Scandinavia was still new to most Americans. The smorgasbord concept debuted in the U.S. at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, with traditional ingredients like pickled herring, cheeses, and cold cuts. Garneau’s was different—his “American Style” buffet did have Swedish meatballs but included another 75–100 dishes from potato salad to stuffed prunes to a 90-pound beef round roasted for 12 hours.

One profile explained that his concept fit the new “on-the-go, rush-rush life” by offering “the speed of cafeteria self-selection with the glamour of a dinner party buffet.”2 Success brought more locations: one south of Youngstown, another west of the Monroeville Turnpike interchange, one on McKnight Road in the North Hills, and another on Ohio Rt. 21 between Akron and Cleveland.

When smorgasbords made news in the 1940s and ’50s, it was mostly in Minnesota with its large Swedish population, where city councils demanded that sneeze guards be added following sickness outbreaks.3 Early guards were often just a sheet of steel or plastic bolted to a food counter, like a wall. The Swedes who ran smorgasbords insisted their restaurants were already sanitary, and newspapers mocked do-gooders for thinking that germs could harm anyone.4 However, a bigger push for sneeze guards was on the rise from hospitals and school cafeterias.5 Such guards eventually became a required feature of food service though period newspapers continued to call them unnecessary.6

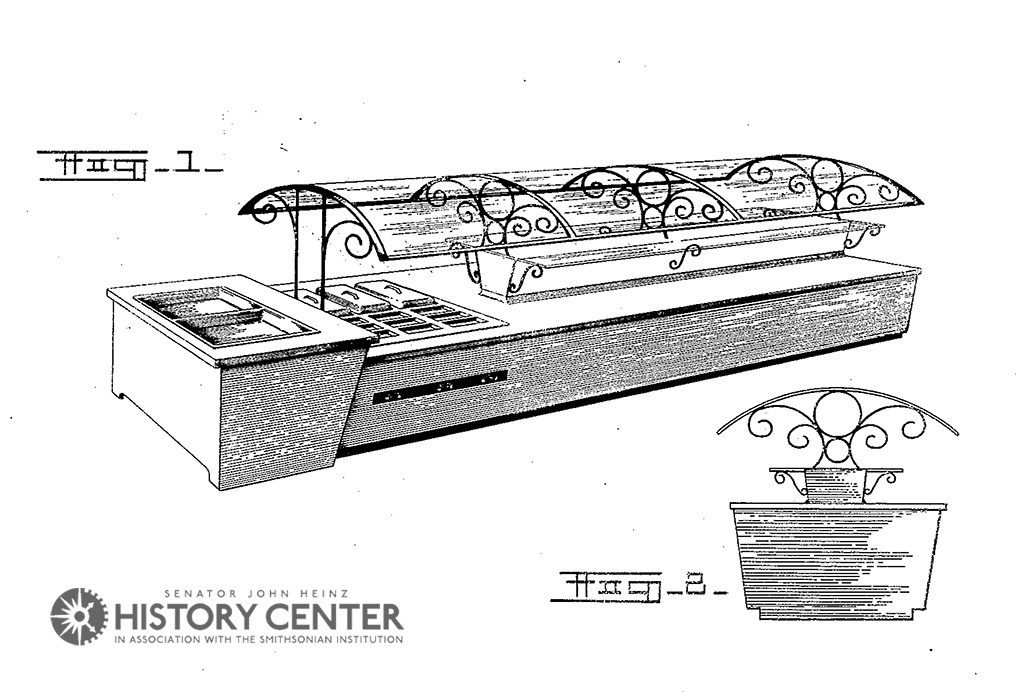

Garneau was a driven entrepreneur, but also a germaphobe. It was not just sneezing around his buffets that bothered him; he did not like watching people bend over to smell each entrée or side dish, all while breathing their germs onto the food. So Garneau designed his own table with a built-in, overhead sneeze guard—a curved, decorative glass pane arching gracefully over each side, supported by ornamental ironwork. Others’ add-on guards performed the same basic function but made food hard to see or reach. Garneau’s sneeze guards combined all the necessary elements into one elegant package; they were already in his restaurants when he received a patent in 1959 for the “Covered Food Serving Table.”7

By 1965, Garneau felt that buffets were running their course and would never be fully sanitary. He then dreamed up a railroad-themed steakhouse called the Golden Spike, its name a nod to the driving of the ceremonial golden spike that completed the transcontinental railroad in 1869. His first location was on Route 51 near the Pleasant Hills Cloverleaf. The building resembled an old train station and had staff dressed in period outfits, railroad memorabilia décor, sound effects, and a miniature train to deliver drinks and bar snacks.8 In 1968 he opened a lavish Golden Spike in downtown Pittsburgh on 6th Street, which was being touted as the city’s new entertainment district. Garneau’s cocktail lounge faced the Loew’s Penn Theater, then closed but set to reopen as Heinz Hall in 1971. Escalators led downstairs to the 170-seat rail-themed restaurant and the lavish new Fiesta Theater.9

In 1969, the centennial of the actual golden spike, Johnny Garneau’s restaurants were at their peak. He was inducted into Hospitality magazine’s Hall of Fame that year for outstanding achievements in the food service industry and his community affairs.10 He tried expanding nationally but by the late 1970s was onto yet another innovation: the “Pretz” pretzel-bagel bun, to be sold through a chain of Professor Pretz’s sandwich shops, including a storefront also on 6th Street in the Roosevelt Building a half-block from the Golden Spike.11

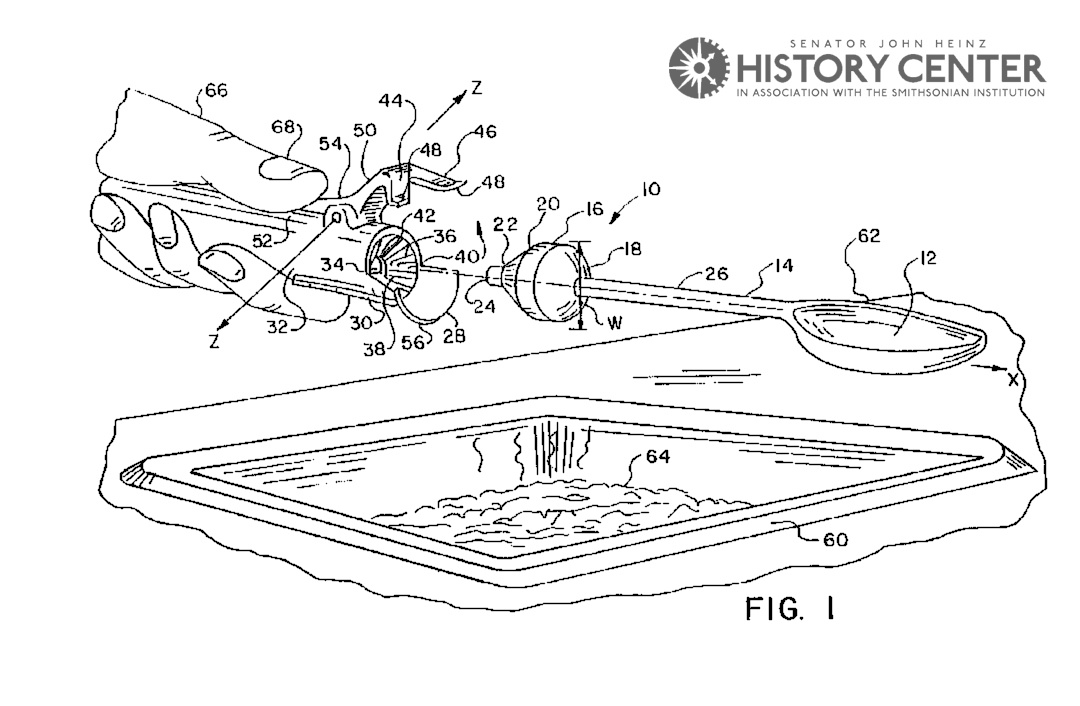

By the 1980s, Garneau had sold the smorgasbords and Golden Spikes but remained interested in food safety. The sneeze guard became standard at buffets long ago, yet little had been done to address cross-contamination by customers using the same food utensils (or worse, their own forks and spoons) to fill their plates. Of course, Garneau had a solution for that too: the “Attachable and Removable Handle for Food Serving Utensils.” Each buffet customer got their own sanitary handle to attach, then un-attach, from the line of serving spoons.12

As his 1997 patent explained, “After filling their plate with food from the buffet table, the customer simply disposes of the handle.” Unlike the sneeze guard, this invention never caught on—perhaps it was too cumbersome for customers or too much labor to maintain. Garneau passed away in 2013 but with the renewed interest in controlling germs and food safety, maybe his sanitary food handle will become one more way he changes how we eat out.

1 See for example, “Ninth Year to be Marked by Garneau Restaurants,” Oil City Derrick, April 3, 1958, p. 5.

2 “Try American Style Smorgasbord,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 29, 1959, p. 11.

3 “Smorgasbord Goes on Trial in City Case,” [Minneapolis] Star Tribune, April 24, 1952, p. 17.

4 “A Sacred Institution is Threatened,” Des Moines Register, April 29, 1952, p. 10.

5 The earliest newspaper mention I could find is an advertisement for bids to equip a high school cafeteria in 1948: “3 sections of Sneeze Guard” for Wm. S. Hart Union High School Board of Trustees, The [Santa Clarita] Signal, Feb. 26, 1948, p. 6.

6 “‘Sneeze Guard’? What’s Next?,” [Dayton, Oh.] Journal Herald, Oct. 21, 1958, p. 3. Articles also often included an explanation, sometimes sarcastic too, such as “‘sneeze guards’ (plate glass food protectors, to the non-professional),” per Adaline Moore, “Caligraphs,” The Bakersfield Californian, March 19, 1949, p. 7. Along with health codes, adding sneeze guards became necessary to secure the National Sanitarian Foundation Seal of Approval.

7 Covered Food Service Table, Patent No.186,927, John P. Garneau, Clarion, Pa., Application March 10, 1959, Serial No. 54,924. The other patents referenced are for a Refrigerated Display Case and a Lawn Swing Canopy, i.e. a curved covering.

8 William Allen, “John Garneau Stakes Hopes in Golden Spike: ‘Railroad’ Smorgasbord Set Near Route 51 Cloverleaf,” Pittsburgh Press, March 5, 1965, p. 18.

9 William Allen, “Johnny Garneau Plans to “Spike” Triangle This Summer,” Pittsburgh Press, March 17, 1967, p. 40; and William Allen, “Garneau Chugging Into Triangle with Third ‘Golden Spike,’” Pittsburgh Press, March 8, 1968.

10 “Restaurantuer [sic] Cited by Trade Magazine,” Oil City Derrick, Jan. 31, 1970, p. 88.

11 William H. Wylie, “Proposed Fast-Food Chain Stakes its Future on a Bun,” Pittsburgh Press, Jan. 23, 1979, p. 15.

12 Attachable and removable handle for food serving utensils, US 5699614A, John P. Garneau, Sr., Dec. 23, 1997.

Brian Butko is Director of Publications at the Heinz History Center, and author of books on Kennywood Park and Isaly’s. Look for his full history of Garneau’s food empire in a future issue of Western Pennsylvania History magazine.