Beware the Ides of March, a seer warned Julius Caesar. For classic amusement parks, the day of reckoning often occurred in the weeks following Labor Day, when summer’s end culminated in the announcement of a park’s demise. In this region, White Swan Park, Rainbow Gardens Park, Idora Park, and Geauga Lake Park, just to name a few, all closed for the last time in September.

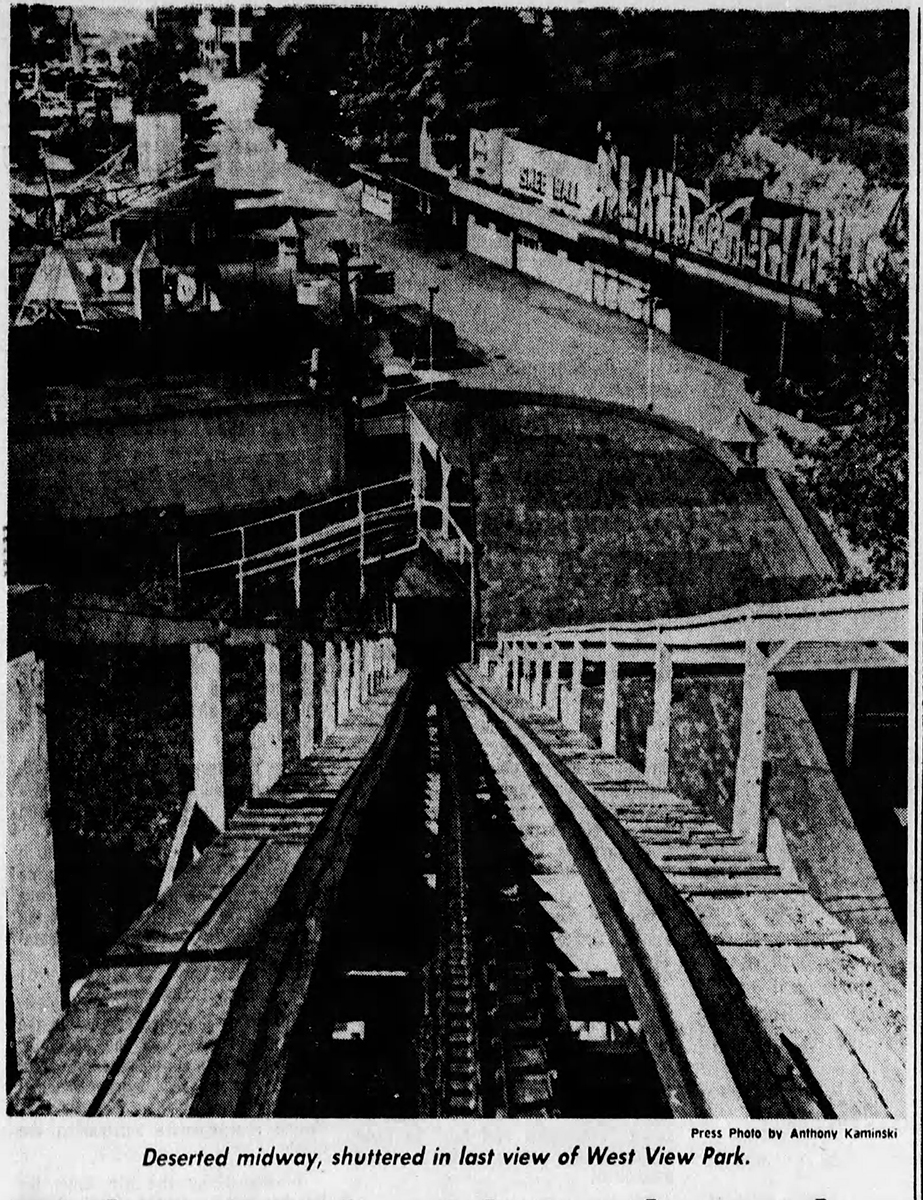

Forty years ago, in September 1977, this same fate befell West View Park. Years of rumors about the park’s precarious existence were confirmed when the 1977 season proved to be its last. Many mourned West View’s closing, but not everyone was sorry to see it go. Citing increased traffic and a changing culture, some saw the decision as a benefit. One woman insisted in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 1977 that the park “should have closed years ago. I hope they build a nice, big shopping center. It might reduce our taxes.”

Amusement park lovers probably cringed at that statement. But it’s a good reminder that places like West View, which opened in 1906, were always part of a larger transportation and commercial infrastructure. They balanced patron enjoyment against competing factors such as changing technology, shifting entertainment options, economic impact, and land use. (Indeed, two of the parks listed above, Rainbow Gardens and White Swan, closed due to highway construction projects.)

The same, of course, can be said of any shopping mall, bowling alley, or video arcade. Yet how many defunct shopping malls elicit waves of nostalgia from those who once shopped there?

In recent years, fans who mourned the loss of a favorite amusement park have seen pieces of a few of them return, albeit in different settings. In Cleveland, Ohio in 2014, the Western Reserve Historical Society welcomed back the carousel that once graced Euclid Beach Park. In Youngstown, Ohio, a husband and wife team created their own museum honoring Idora Park. Idora’s carousel, now known as Jane’s Carousel, spins again in Brooklyn Bridge Park in New York City. Even parks that have been gone for generations still attract enthusiastic audiences when books and programs are presented about them, such as the recent release of Brian Butko’s new book on Luna Park, a historically important but short-lived park that once stood in Oakland (buy the book!).

So, what is it about lost amusement parks that evokes such nostalgia?

Part of it is psychology. These places were designed to make a lasting impression. From the start, amusement parks were structured to draw people into a calculated physical and sensory experience that pushed all the right buttons to make them feel good: “safe” thrills, curving pathways that direct crowds from one location to the next, the exciting novelty of bright lights, strange sights and sounds, the anticipation of being scared, a day away from “normal.”

The impact was especially strong for those who grew up near these places and continued going to them and sometimes working in them during their teenage years, a period when science confirms that many people form attachments to cultural experiences such as music that last a lifetime. When someone says the memory of a park “takes them back to childhood,” they really mean it. How many places can connect so many generations in a shared experience the way that Kennywood still does today? When such places disappear, the psychological gap people feel is real, even if they hadn’t been to the actual park in years. That was the reality with West View, which had suffered through multiple seasons of dwindling visitation.

For neighborhood parks, this resonance was also shaped by their ongoing relationship to community group such as schools, businesses, and churches. At its height, the tradition of annual picnics and ethnic days was more than a one-day event. Planning, anticipating, and reliving the stories of each year’s visit became a summer ritual that shaped the experience of childhood. The same was true for promotions connected with local businesses: how many “West View” kids spent every summer strategizing to get mom or dad to buy the items advertised in the “Thorofare Days” coupons for free ride tickets?

Such memories can translate into interest in older parks as well. The thought of a long lost technological playground filled with fanciful architecture, bright lights, and strange attractions once standing where auto dealerships and business offices (or shopping centers) now stand can trigger the same reaction that drives nostalgia for places that existed within more recent living memory.

Of course, amusement parks didn’t appeal to everyone. And for years they were distinctly unwelcoming to the region’s African American residents, some of whom worked together in 1945 to establish their own small park, Fairview Park, out in Salem Township. It too once featured a carousel and roller coaster.

Today we have so many entertainment options that no single attraction will ever dominate public imagination the way that a few shared experiences – amusement parks, movies, the circus – once did. We simply have too much to choose from.

But perhaps that’s why for some people nostalgia for these lost places runs so deep. After all, who doesn’t still have their moments when all they want, as the Pittsburgh Daily Post described West View Park in 1906, is a day at a place “just far enough away from the city to be out of reach of all dirt and grime and away from the noise and turmoil perpetually present in ‘The Workshop of the World?’”

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.