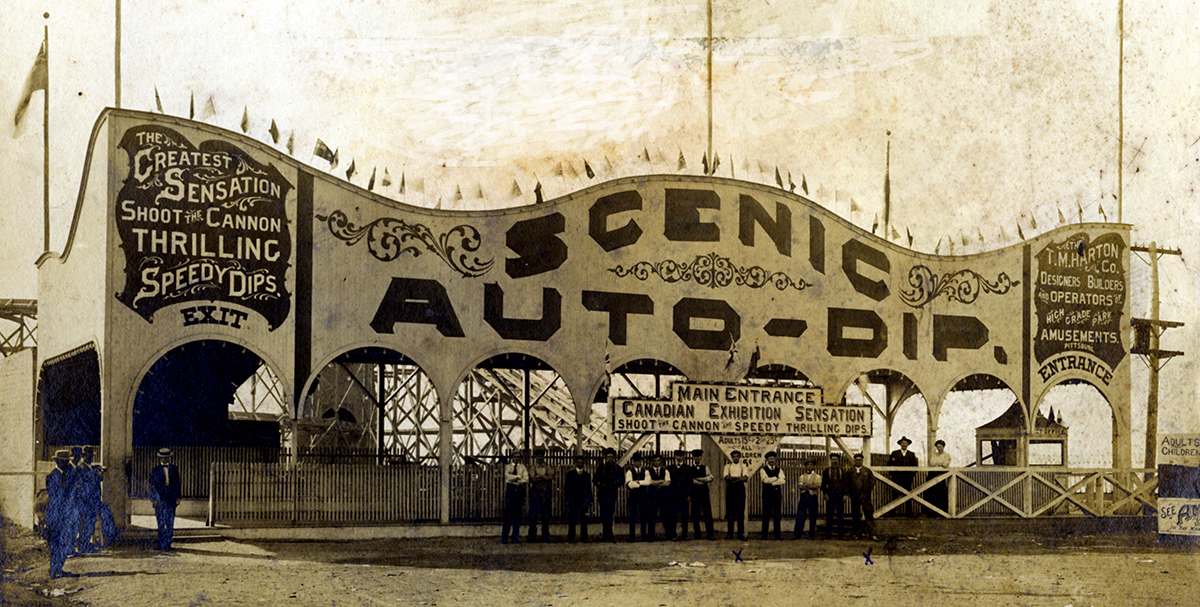

Sometimes the research for one story naturally leads into another. While working through collections related to a recent post about lost amusement parks, I came across this great image for the Pittsburgh-based T. M. Harton Company’s Scenic Auto-Dip. The ride thrilled visitors to the annual Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto between 1902 and 1906. It cost 15 cents to ride or two people could ride for 25 cents. That might sound very reasonable today, but it was considered quite pricey back in the early 1900s, when Pittsburgh’s first nickelodeon made quite a smash, because, yes, it only cost a nickel.

The photograph is a great reminder of the remarkable legacy of multiple people from this region who manufactured the thrilling ups and downs of roller coaster rides well into the 20th century.

The row of workers standing in front of the Scenic Auto-Dip includes at least one and possibly more members of the Vettel family, the multigenerational clan of German immigrants who played such an integral role in building and maintaining attractions at both Kennywood and West View Park for so many years. At the time, brothers Erwin, Edward, and Andrew Vettel all worked for T. M. Harton, the amusement builder who founded West View Park in 1906. All of them built roller coasters.

Erwin became the most international of the three Vettel brothers, spending much of his time abroad building exciting new coasters in places such as England and Germany. Erwin’s son, Andy, longtime park superintendent at Kennywood and later chief architect of the beloved Thunderbolt (1968), recalled that his father spent as much as 80% of his time overseas between 1906 and 1929.

Eventually the Vettel family contributed to the creation of coasters across the United States, from the Cyclone at Lakeside Park in Denver, Col. and the Zephyr at Ponchartrain Beach in New Orleans, La. to the Blue Streak at nearby Conneaut Lake Park. T. M. Harton, meanwhile also reportedly constructed more than twenty coasters between 1902 and 1927, most of them in communities across Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, and Ontario, Canada.

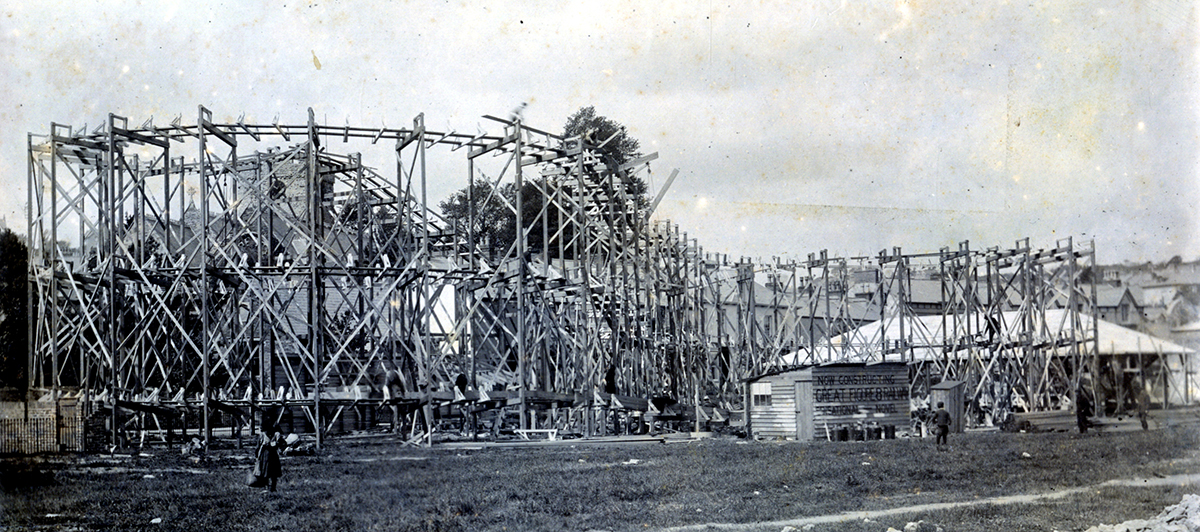

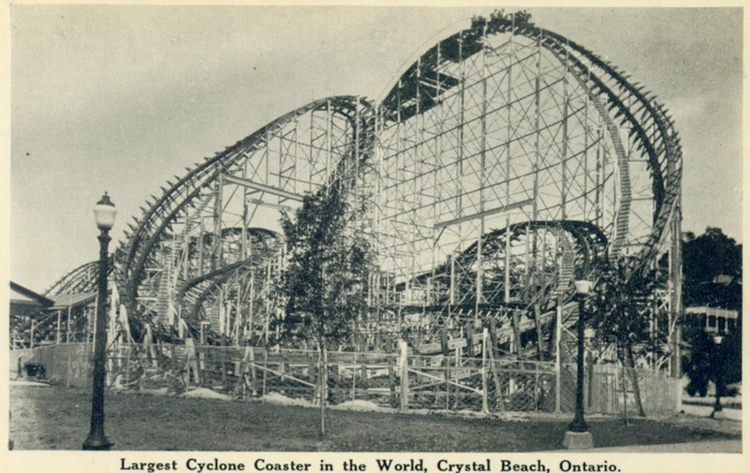

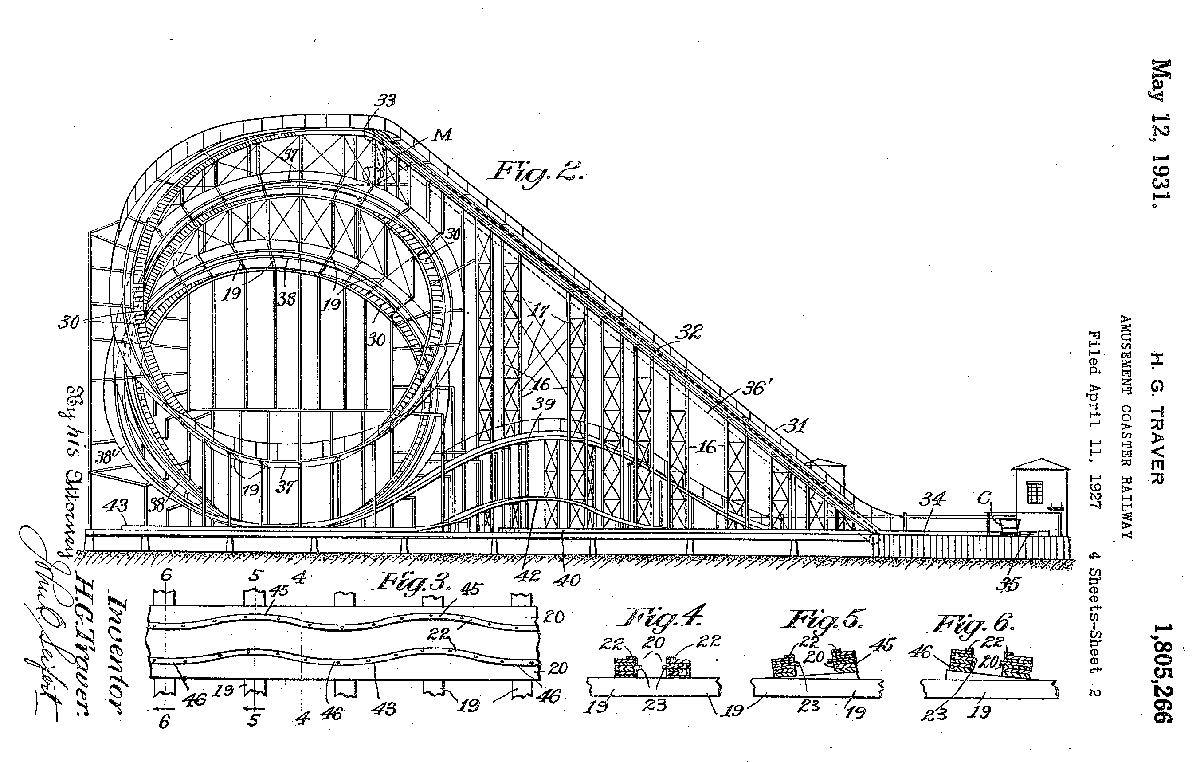

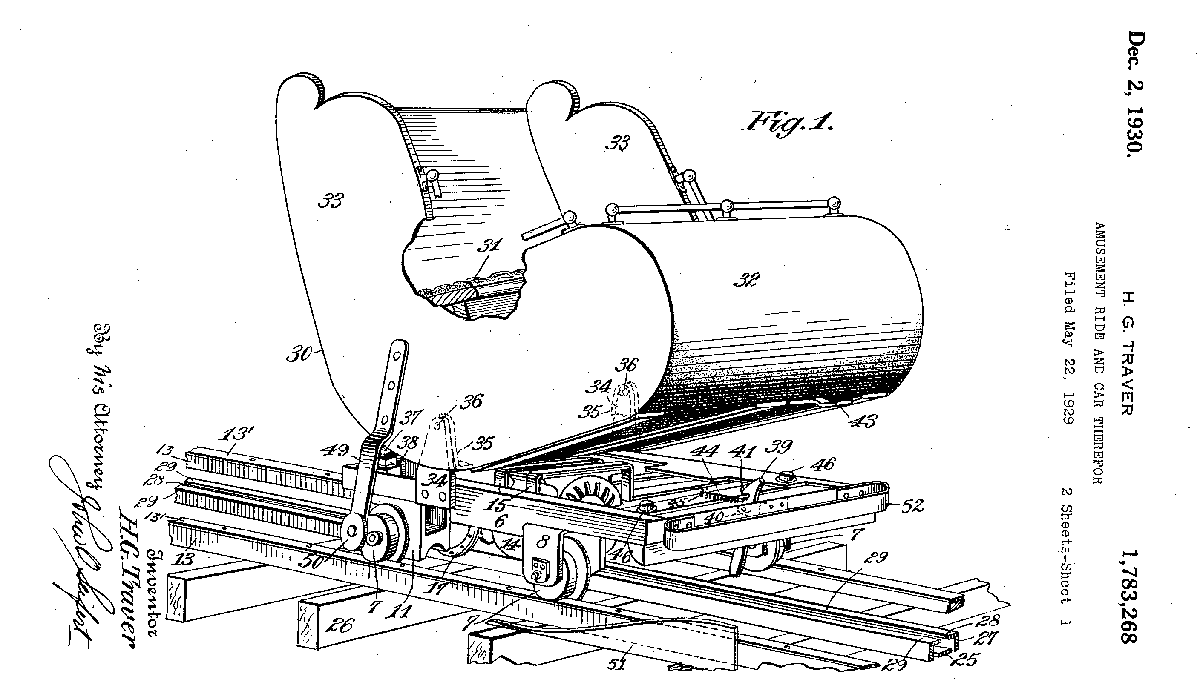

The Vettel brothers and T. M. Harton were not the only amusement builders who called this region home. Looking north again to Canada, a monstrous coaster christened the Cyclone opened along the shores of Lake Erie at Ontario’s Crystal Beach Park in 1927. At more than 90 feet high, with twists and turns that almost defied the laws of physics, the coaster heralded the vision of one of the most unique amusement minds of the century: Harry G. Traver.

Traver was born in the Midwest, honed his engineering expertise with several electric transportation companies, and started his first amusement business in New York City. Around 1919 he relocated to Beaver Falls, Pa., where his Traver Engineering Company made the small industrial community one of the world’s largest producers of amusement park rides. Traver’s creations, reported the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 1928, made a young man “squeeze his breath and catch his best girl friend.” The paper noted that the company’s modest shop (“carefully hidden from irate mothers”) produced rides for locations across the globe, from Budapest and Bombay to New Zealand. The paper noted, “All the world, it seems, comes to Beaver Falls for its roller-coasters.”

And what rides they were. Traver coasters featured steep spiral drops that twisted the front of a train before the back had even crested the hill, undulating tracks that pitched riders back and forth, and figure eight sections that nearly flipped riders into a vertical side position. Looking at images of them today, it is nearly impossible to believe that some of these machines were actually built.

Fittingly for Western Pennsylvania, Traver’s most ingenious coasters used steel supports rather than wood-only construction. The steel helped bear the stress of Traver’s extraordinary rides. The steel frames were reportedly manufactured in Pittsburgh, then shipped to their destination. His firm advertised a line of early “steel-only” coaster that were really a combination of steel and laminated wood, but the point had been made: Traver believed the future lay in metal track. Although many of Traver’s most famous rides, such as Crystal Beach’s ferocious Cyclone and its two sister coasters, the Lightning at Revere Beach in Massachusetts and the Cyclone at Palisades Park, New Jersey, proved so rough on both riders and maintenance staffs that they lived relatively short lives, they remain legendary in the minds of coaster enthusiasts. (They are fondly remembered as the “terrifying triplets,” although Traver, intending no irony, advertised them as his model line of “Giant Cyclone Safety Coasters.”)

The work coming out of Harry Traver’s Beaver Falls shop presaged the creation of today’s extreme coasters, a broader heritage that the Vettel family also helped to grow and preserve through the years.

So, the next time you take a seat in the Phantom’s Revenge at Kennywood and get ready for that plunge through the track of the Thunderbolt, remember (if you can) that the delicious terror you feel is the legacy of multiple Western Pennsylvania innovators.

For further reading

Bob Bauder, “A life of wild rides, full of ups and downs, Harry Traver,” The Times (Beaver, PA), July 2, 2006.

Robert Cartmell, The Incredible Scream Machine: A History of the Roller Coaster, Ohio: Amusement Park Books, Inc., and Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1987.

Mike Funyak, “ ‘Round about Pittsburgh: Roller Coasters Run in the Family,” RMU Sentry Media.com, March 18, 2014.

Richard Munch, Harry G. Traver: Legends of Terror. Ohio: Amusement Park Books, Inc., 1982.

George Swetnam, “It Drops Like a Thunderbolt,” The Pittsburgh Press, May 19, 1968 (This is a great feature about the Vettel family in connection with the opening of the Thunderbolt at Kennywood Park.)

“30 Years of Ups & Downs (& Arounds),” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 10, 1962.

You can see video clips of the Crystal Beach Cyclone in operation here or here.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.