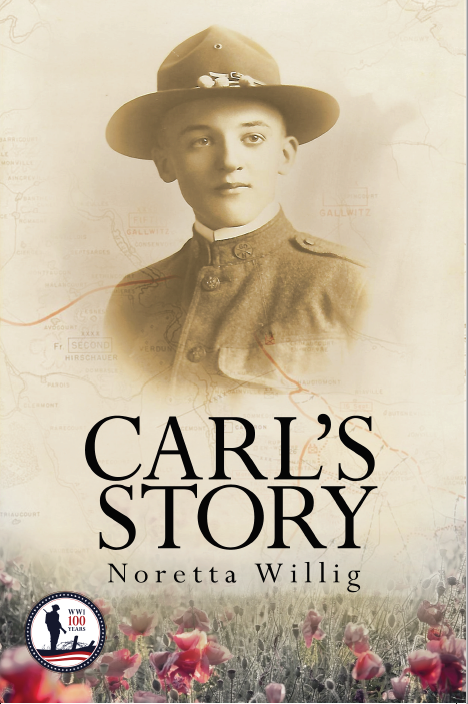

Read the article by Noretta Willig about her uncle Carl’s WWI story in the Winter 2017-18 issue of Western Pennsylvania History or the full story in her book, “Carl’s Story,” available at: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Books A Million.

In the American Cemetery at Thiaucourt, France, stands a doughboy, larger than life. Dressed in a summer tunic, bloused pants, and leggings, this serious soldier notches his thumbs in his belt that holds his cased pistol and his field helmet. His still gaze looks out over the silent rows of white crosses. Strong, handsome and resolute, he seems so young. Above his head, the inscription, in French, translates: HE SLEEPS FAR FROM HIS FAMILY IN THE GENTLE LAND OF FRANCE. On the pedestal, below, the motto continues in English: BLESSED ARE THEY THAT HAVE THE HOME LONGING FOR THEY SHALL GO HOME. My uncle, Carl Willig, died on Sept. 16, 1918, at the battle of St. Mihiel.

Fifty-six days before the end of the war and 30 minutes before his replacement arrived, a high impact shell struck and killed Carl. According to an eyewitness, “He suffered no pain, dear friends.” As the battle rolled quickly on to the Meuse-Argonne, in what we now call “the fog of war,” Carl was lost. To his parents, his brother, and all who ever knew him, he was lost forever. Three generations continued to experience that loss, an unresolved sorrow that reappeared persistently. Carl’s brother, my father, suffered a daily frenzy until he found a way to have his son, my brother, exempted from military service in World War II. Again and again, our dinner table conversation ended abruptly as my dad said, “No son of mine will ever go to war! Ever!” But, over many years, Carl became an ancestral shadow, no longer a reality to anyone.

Then, on Nov. 10, 2008, the eve of the 90th Armistice Day, my phone rang and a genealogist from Oregon working for the U.S. Army identified me as Carl’s next of kin. “They have found something,” she said, explaining that she knew nothing more and that the Army would call me with the full story. From that second, I was compelled—I would even say—driven to write “Carl’s Story.”

My research took me first into old family photos. Looking at them caused me to make connections with members of my family, some of whom I knew quite well and others whom I never heard of. The bonds I discovered looking at those pictures and found in later research brought meaning and understanding to relationships long cast away in memory. My grandfather, whom I never met, emerged as a towering patriarch. My grandmother became “Carl’s heartbroken mother,” rather than the silent, distant woman always dressed in black I knew as a child. My dad, the rock foundation of our family, surfaced as the “second son” who felt the weight of his obligation to succeed two-fold. The memories of my Aunt Gussie’s stories proved to be the treasured, last link connecting me with my long-deceased family.

Representatives of the Army visited my home and brought with them hundreds of pages of evidence, gathered over two years, illustrating the scholarship of Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC)—anthropologists, historians, as well as forensic and materials specialists, seventeen Ph.Ds., in all. The information they presented led to an indisputable conclusion. By the single most indestructible part of him, a gold crowned tooth, Carl was finally known.

They also introduced me to a French organization called Thanks GIs, whose mission is to recover the lost remains of American soldiers. In World War I and again in World War II, Eastern France was liberated by the same 5th Division of the U.S. Army. Most in the organization were only children when American troops freed them from their German occupation. As a display of their continuing gratitude, on every holiday, American or French, these men, women, and today’s children and grandchildren honor their liberators. When I later travelled to France to meet them, they identified their commitment as “the least we can do for them who did so much for us.”

While visiting in the kitchen of the president of Thanks GIs, I learned of the group’s part in Carl’s remarkable story. With animation and pride, the rugged man at the head of the table told his tale. One day while searching for artifacts, he stumbled in an isolated wood near an old farmhouse. It wasn’t a root that he tripped on; it was a bone, a human bone. So began Carl’s accidental, but fortuitous discovery. A long and extraordinary series of coincidences, described in the book, continue the story of his identification. Then, after almost a century, Carl came home. Home at last.

With full military honors, Carl was buried next to his father, mother, and brother in the family plot. As he was laid to rest for the final time, a train whistle sounded over the hills of his hometown, McKeesport, Pa., and the now-idle steel mill where he worked.

Carl was only 18 years old when he enlisted. He was the son of a German immigrant, and he marched away to a place called “over there.” Why did he go? To escape that hot and gritty mill? To prove his loyalty to their New World? To answer President Wilson’s patriotic call? To have an adventure? We will never know that answer. His story is not the drama of a valorous moment in a war that made him the hero of the battle. He was just a boy who marched away to serve and die for our country, in the war that is often forgotten. With the passing of all who knew him, Carl, too, was nearly forgotten—until my phone rang.

Now Carl is remembered and perhaps “Carl’s Story” will hold him in the minds and hearts of those who read the book. It has been my honor to write “Carl’s Story.” In every time and place, from the American Revolution to the U.S. War in Afghanistan, we must respect and revere the lives and the memories of all those who sacrificed so that we may live free.

As we commemorate World War I, at its 100th anniversary, we need to call to mind the millions of soldiers who marched away and the many thousands who have never returned. Numbers and statistics are not enough. Each of them has his story and all of them had the longing for home.

Raised in McKeesport, Noretta Willig graduated from Ohio University and the University of Pittsburgh. After working in publications, she taught literature at an area high school. Since retiring, she has traveled in all 50 states and many foreign countries, including to the battlefields of France.