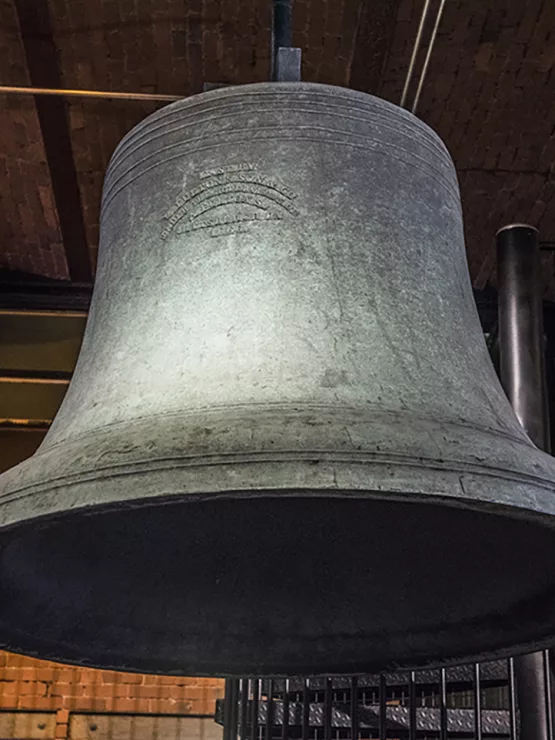

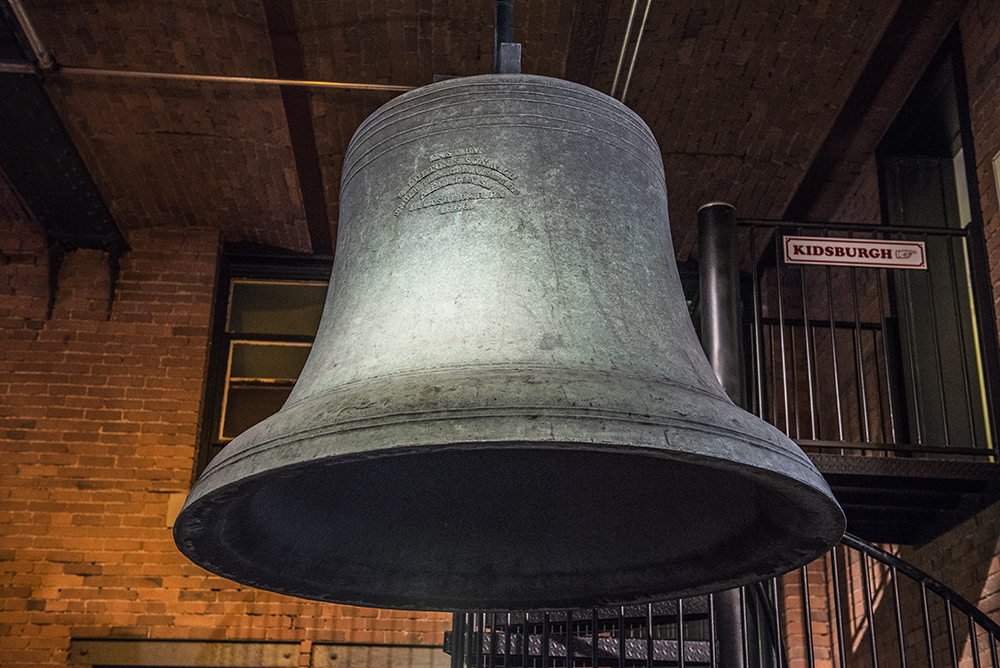

Today, the old bell hangs in the History Center’s Great Hall. More than 70 years ago, it nearly landed on the scrap pile. During the dark days of World War II, the bell (which was donated to the Western Pennsylvania Historical Society in 1920) generated debate. Should it be melted as scrap for the war effort? Ultimately, the answer was no.

What saved the bell was the meaning attached to it by a disaster from another century. Every year since the early 1900s, just after noon on April 10, the old bell was used to ring out “1-8-4-5,” remembering the terrible day when flames from a washerwoman’s fire near Ferry Street exploded in the tinderbox of antebellum Pittsburgh, igniting an inferno that burned for nearly seven hours and consumed more than 1,000 buildings.

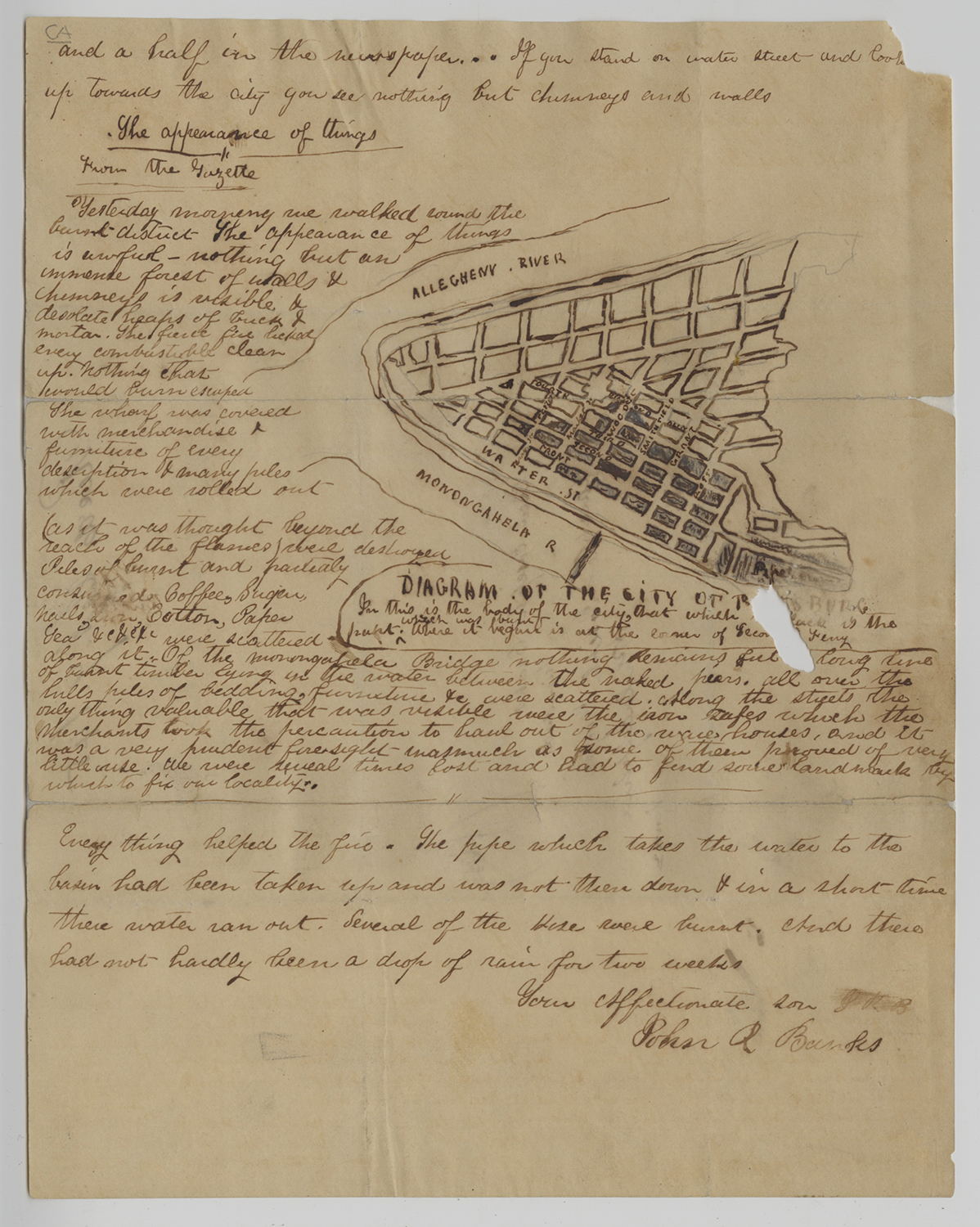

For a century, the Great Fire stood as the event by which Pittsburgh’s history was measured: the “before” and “after” point. Burned streets were rebuilt and businesses resumed, but memories lingered. Within a year, artists issued dramatic images of flames devouring the city. The terror even inspired a crime novel (“The Smoky City: A Tale of Crime,” 1845). Fire souvenirs were collected. Elegant mantle clocks, saved hastily from the flames, testified to the double-edged nature of time in a disaster. Melted wrenches evoked the heat. People bought fire-singed plates as souvenirs, their surfaces transformed by the interaction of flames and straw packing materials. Today, examples of these artifacts are on display in the History Center’s new Visible Storage.

Time shifts the meaning of things. The Carnegie Museum displayed “fire relics” in 1908 to mark a milestone of the city’s Sesquicentennial progress. By 1933, in the midst of the Great Depression, the Pittsburgh Press featured the fire in its “Pittsburgh in a Pinch” series, underlining the city’s resiliency. During World War II, the fire took on its greatest meaning as the real flames of 1845 mirrored the destruction of a global war. And each year, the bell tolled. As the 100th anniversary approached in 1945, the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania began planning a grand commemoration with parades and speeches. They even ran a contest offering a $50 war bond to anyone who uncovered the real name of the “lady who started the fire” in 1845.

The anniversary saved the old bell. Questions about its fate arose in September 1942 as the war reached a low point. Surely the bell could serve a greater purpose as part of the national scrap drive. But what happened when the commemoration rolled around and the bell was gone? What about the tradition of “1-8-4-5?” The decision was clear: the bell survived to ring again.

That Centennial celebration marked the high point of the fire’s commemoration. The following year, a mix-up prevented the bell from being rung, prompting a brief squabble in the local papers. Although the ringing soon resumed, tales of the fire dimmed. By 1950, The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette observed that the anniversary went “unnnoticed and unthought of” by most people. The annual bell ringing continued while the Historical Society remained out in Oakland, but it quietly stopped by the time the Senator John Heinz History Center opened in 1996. Today, stories about the fire still appear, but with far less frequency. The same war that that nearly consumed the old bell created a new crucible for Pittsburgh in the 20th century, World War II replacing the Great Fire as the event by which the city’s story is measured.

For Further Reading

Len Barcousky, “Eyewitness to 1845: ‘Fearful calamity’ fades quickly,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 6, 2008. Available online.

“Big Bell Pealed to Commemorate Fire,” Pittsburgh Press, April 10, 1902.

Donald E. Cook, Jr., “The Great Fire of Pittsburgh in 1845, or, How a Great American City Turned Disaster into Victory,” Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania Journal, (April 1968): 127-153. Available online.

Peter Charles Hoffer, Seven Fires, The Urban Infernos that Reshaped America. New York: Public Affairs, 2006.

“Pittsburgh’s Big Old Bell to Bong Boisterously Again,” The Pittsburgh Press, April 14, 1946.

“Pittsburgh in a Pinch: Flames under Washerwoman’s Kettle Started $5,000,000 Fire,” Pittsburgh Press, November 13, 1933.

Leslie Przybylek is curator of history at the Heinz History Center.