Reflecting on the legacies of charity given and received in the Iron City

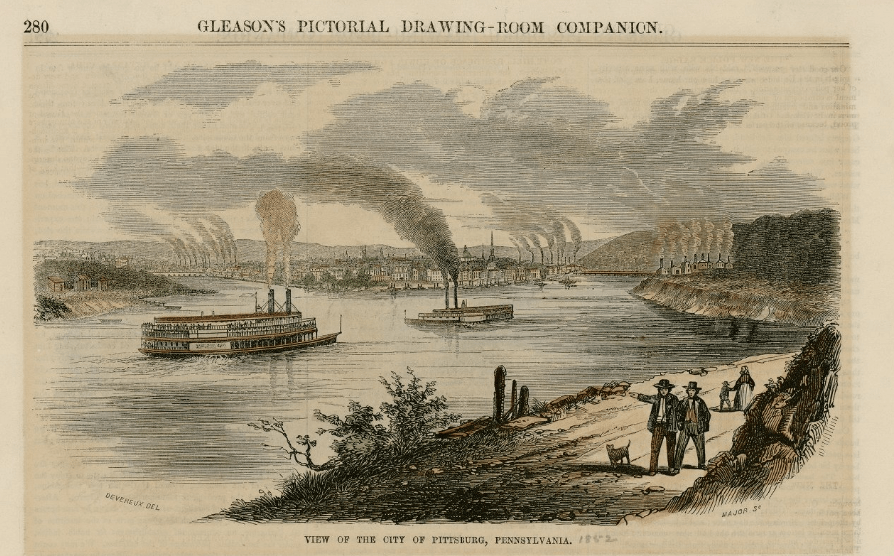

As recent events remind us, tragedy can bring out the best in human nature and challenges us all to help find solutions to meet the needs of our neighbors. Thinking back on the April 10 anniversary of Pittsburgh’s Great Fire in 1845, that event provided multiple examples of generosity from neighboring communities, states, and even a ship stationed halfway around the globe. (Want to know more about the Great Fire? Read about it here.) Ten years later, in the spring of 1855, another event spurred the region’s charitable response into action, illustrated by a pair of rare artifacts now housed in the Detre Library & Archives at the Heinz History Center.

Generosity after the Flames

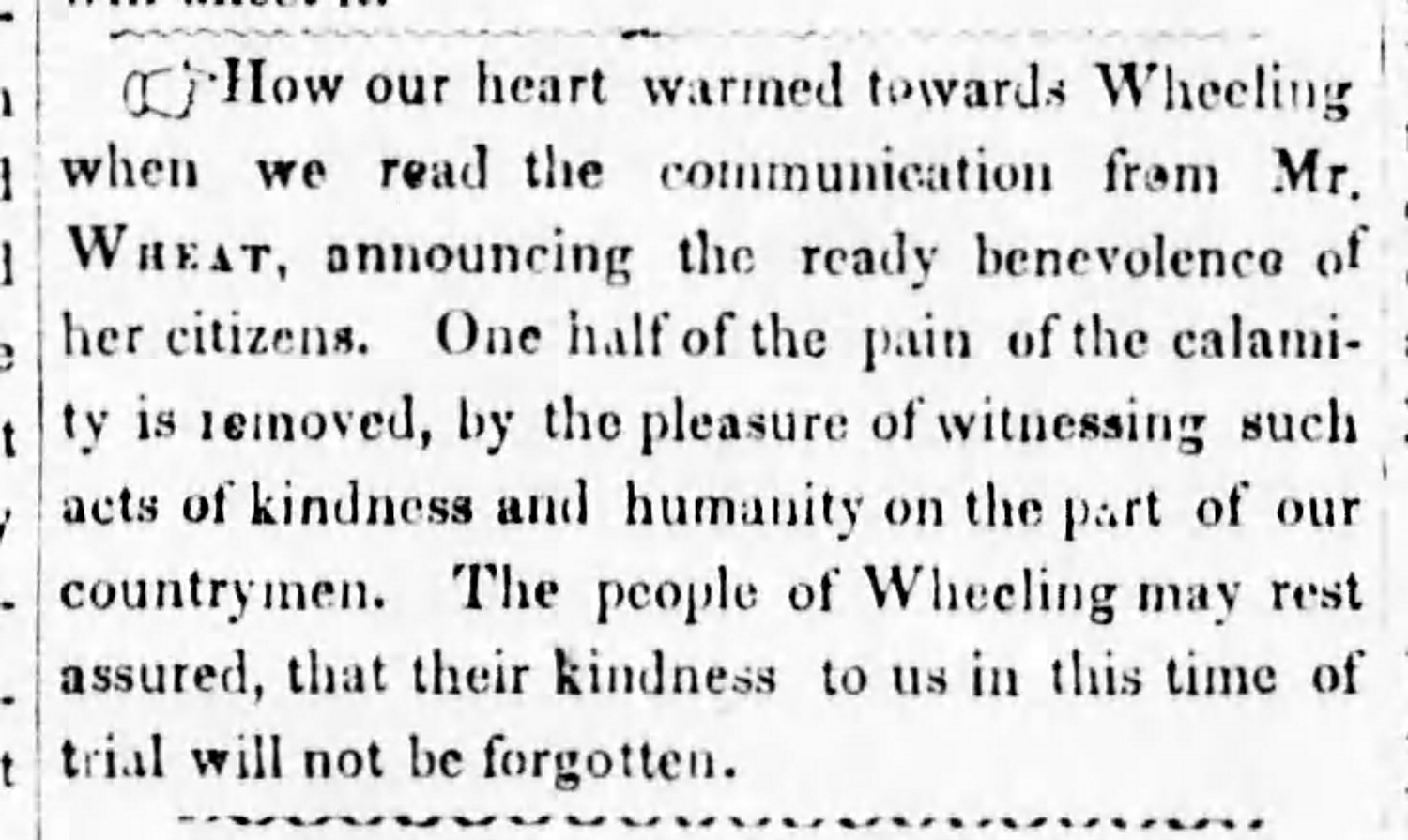

In 1845, as news spread of the Pittsburgh inferno, monetary gifts poured in not just from Pennsylvania, but from other states. These gifts ranged from more than $16,000 offered by Massachusetts and more than $10,000 from Ohio to $329 from New Hampshire. (In fairness to New Hampshire, that was the equivalent of more than $11,000 today.) Communities such as Monongahela City, Meadville, and Wheeling, Virginia sent hundreds of pounds of flour, potatoes, and bacon. Of Wheeling’s generosity, a writer for the Daily Gazette and Advertiser noted on April 18, 1845, “One half of the pain of the calamity is removed by the pleasure of witnessing such acts of kindness and humanity on the part of our countrymen.” Later that summer, in Canton, China, Captain John “Mad Jack” Percival of the U.S.S. Constitution, then circling the world on a three-year diplomatic cruise, gathered his men on deck and told them of the fire in Pittsburgh. A collection taken up by the crew added an additional $1,950 to the city’s relief fund.

A Different Test in 1855

Although severely tested, Pittsburgh rebounded after the Great Fire, and the city soon set about rebuilding. Many remembered the generosity extended by others. Ten years later, residents of the region watched a different sort of disaster unfold. This time, it was their turn to give.

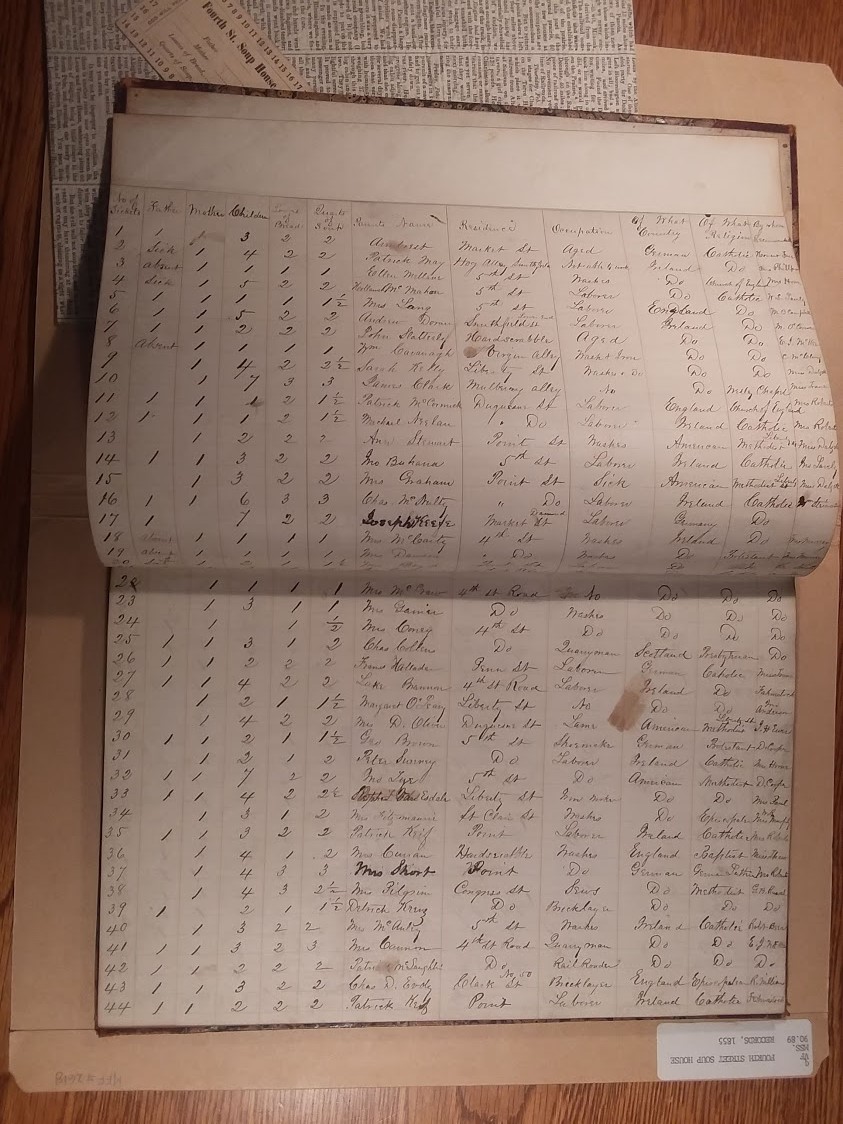

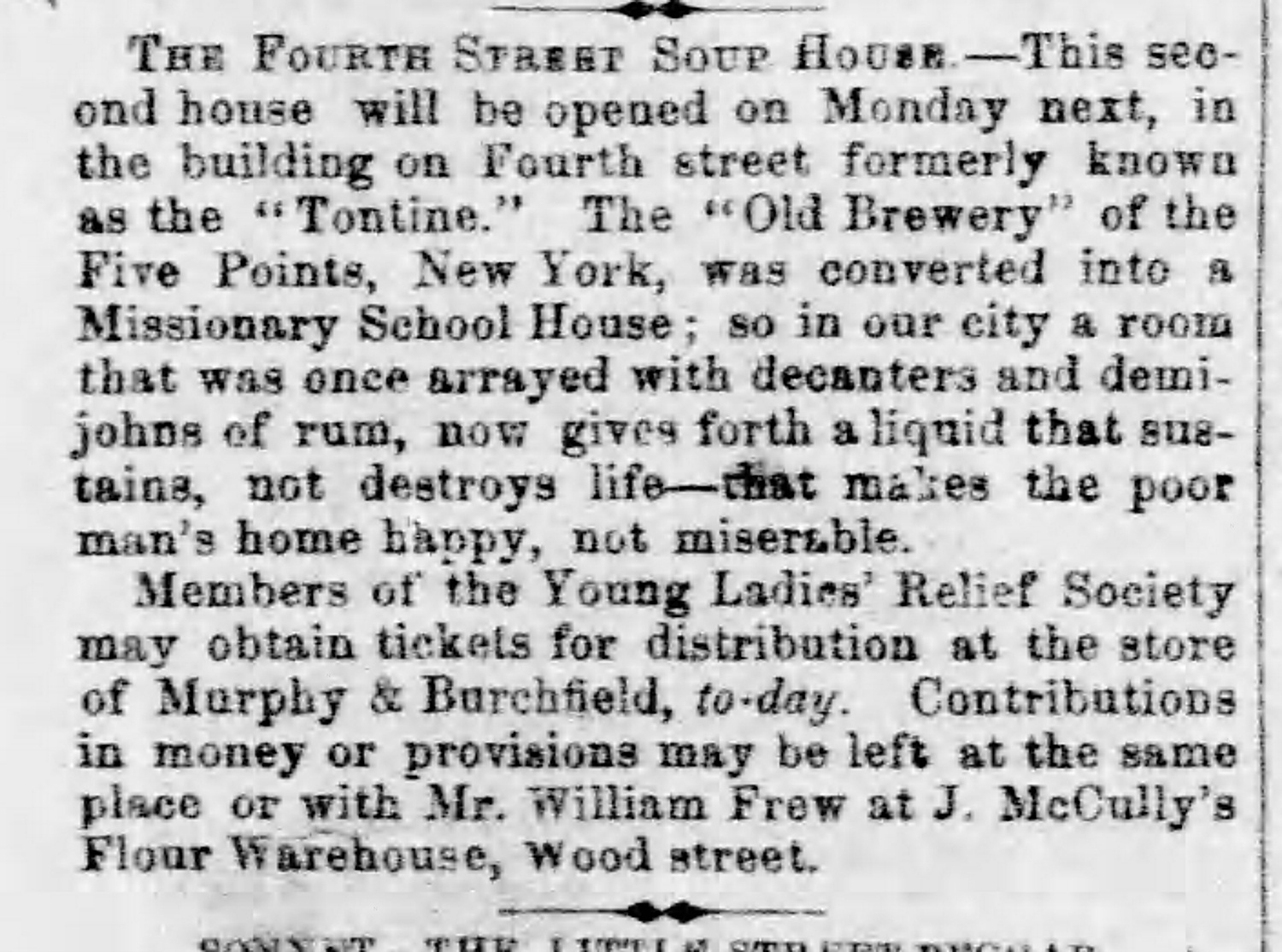

A bound ledger and a small paper ticket in the Detre Library & Archives reveal the details of this story. Someone saved the ledger from the Fourth Street Soup House, a charitable venture that opened in February 1855 in the old “tontine” building in downtown Pittsburgh, once home of a tavern. The Pittsburgh Gazette, in announcing the pending soup house opening on Feb. 5, 1855, mused, “so in our city a room that was once arrayed with decanters and demijohns of rum, now gives forth a liquid that sustains … life.”

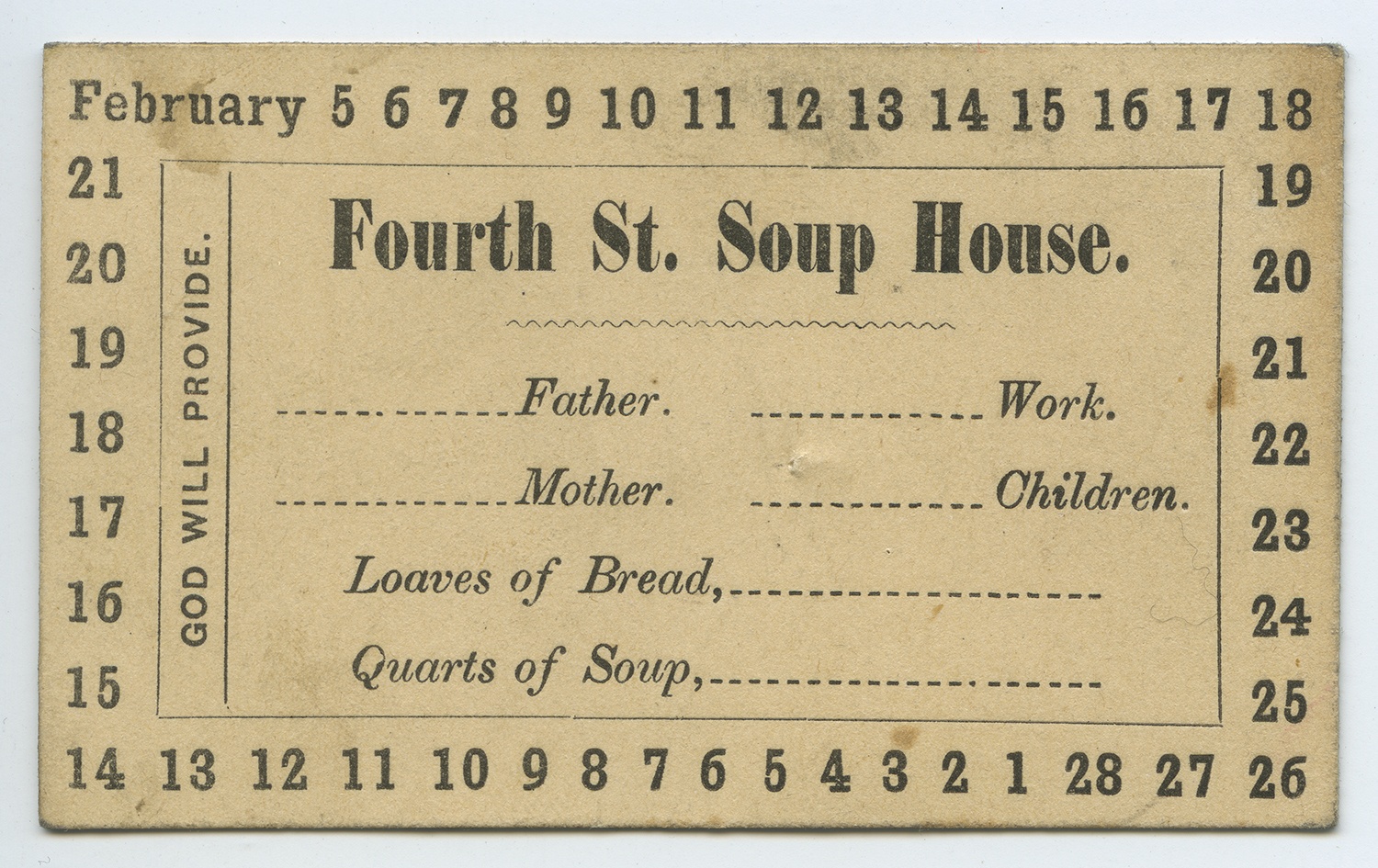

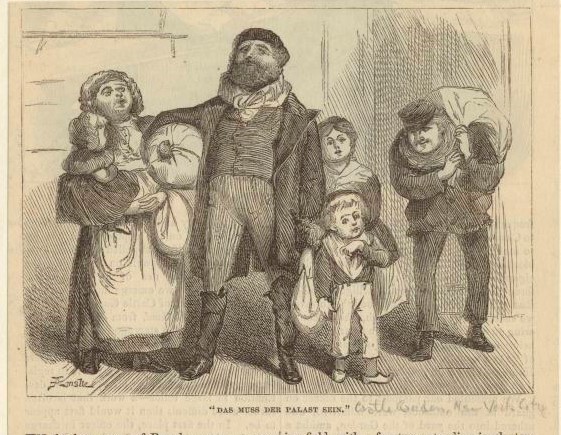

That soup house wasn’t the first one. A harsh winter and a serious economic recession compounded a situation already made difficult by a fall drought. Food was scarce and new immigrants, especially waves of arrivals from the Germanic states, poured into Pittsburgh, creating a perfect storm of need. Following urgent calls in the press and some financial contributions from wealthy backers, the first soup house opened on Seventh Street in Allegheny City on Jan. 26, 1845, distributing 56 gallons of soup that first day. By the end of the week, more than 500 gallons had been consumed, along with 700 or 800 loaves of bread. As calls continued for support, a second soup house opened across the river in Pittsburgh. That was the venture recorded by the ledger now in the History Center. (Eventually, there would be three.) Rarer still, saved along with the ledger was one of the tickets used to distribute food through the month of February 1855, lines included on it to mark who was in the family and how much food they received. The Fourth Street soup house continued its mission until around March 10, 1855, when word of its closure was announced in the local newspapers. As rivers thawed and winter waned, the need was no longer so urgent.

A legacy continued

How many other charitable endeavors has Pittsburgh seen through the years? Some were sustained annual efforts, others, such as this soup house, brief moments within the longer history of this place. If not for someone gathering up and preserving this ledger and ticket, and donating them to the History Center, we would have no physical reminder of this story. As we reflect back upon the Great Fire, upon the scorched plates and domestic items saved from the flames, and confront the challenges of the coronavirus pandemic, we are reminded of the importance of history, and the fact that each small story, each contribution however modest, becomes a part of Pittsburgh’s legacy.

Today, the History Center is again encouraging people to document and contribute stories to our ongoing collecting project on the impact of the COVID-19 challenge. The Fourth Street soup house ledger reminds us why it’s so important to have a place to gather and preserve these materials, allowing future generations to reflect upon what we experience here today.

For more on the History Center’s COVID-19 collecting project, visit this page.

Sources

Donald E. Cook, Jr. “The Great Fire of Pittsburgh in 1845, or How a Great American City Turned Disaster into Victory,” The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine (April 1968): 127-153.

Ira N. Hollis, The Frigate Constitution, The Central Figure of the Navy under Sail (Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Co, 1900), 232. Available online.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.