S. V. Albee and the Great Railroad Strike in Pittsburgh, July 21-22, 1877

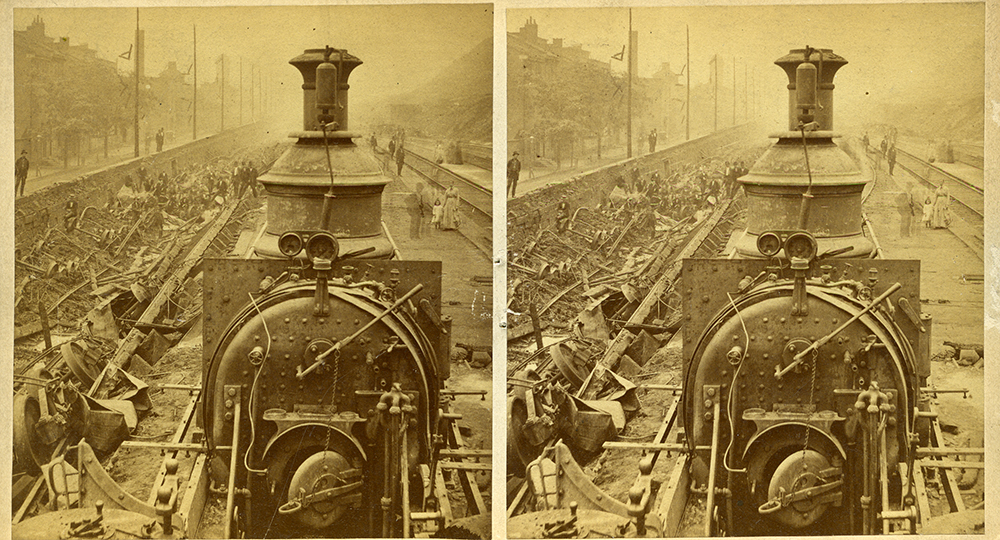

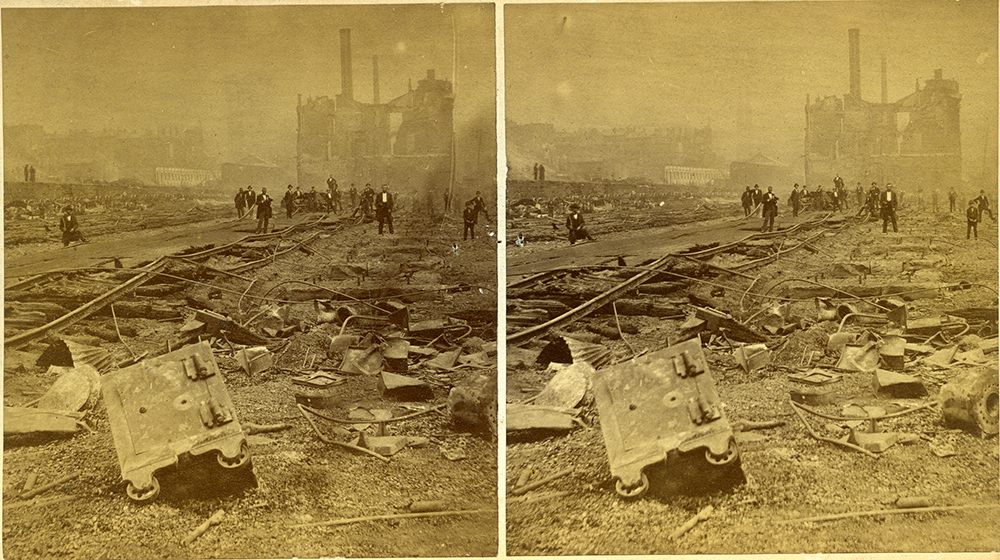

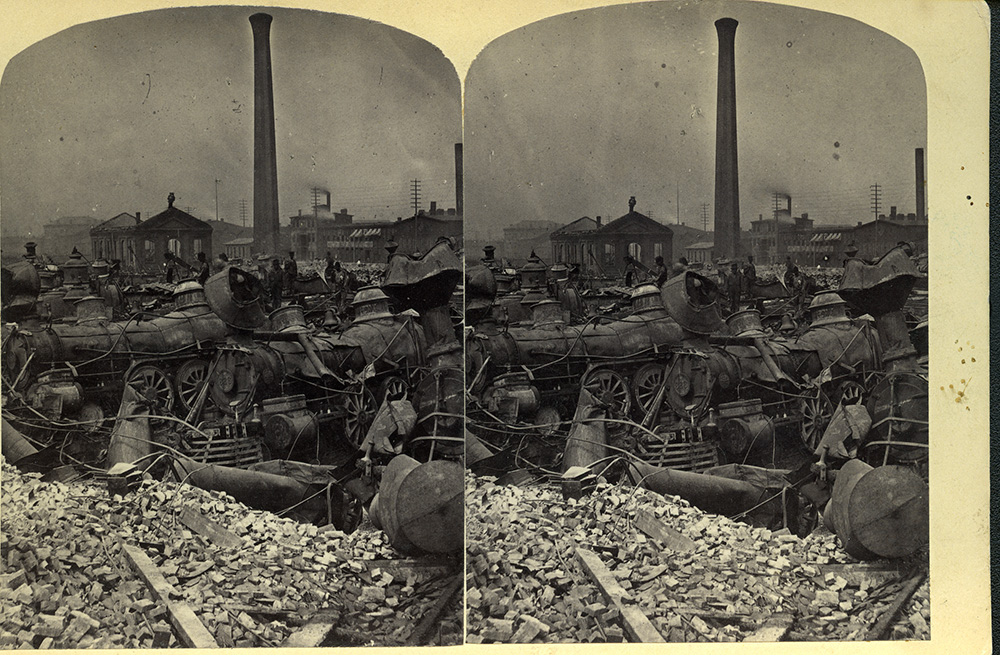

Sometime after July 22, 1877, Pittsburgh photographer S. V. Albee captured an extraordinary series of photographs. Picturing burnt machinery and twisted debris, Albee documented the local aftermath of what scholars consider the first national labor action in the United States – the Great Railroad Strike of 1877.

One hundred forty years ago this month, a labor stoppage that started on July 14, 1877 in Martinsburg, W. Va. – where workers on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad struck to protest their third wage cut in a year – quickly spread along the nation’s rail network. From Maryland to Missouri, railroad workers protested what they felt was a stranglehold by corporate interests. In a nation struggling to recover from a financial panic, with high unemployment and growing immigrant populations, tension was high. In multiple locations, sympathetic workers from other industries such as coal miners and mill workers joined in. For 45 days, national unrest reigned. Some called it the “Great Upheaval.” Many Americans feared it was the start of another Civil War.

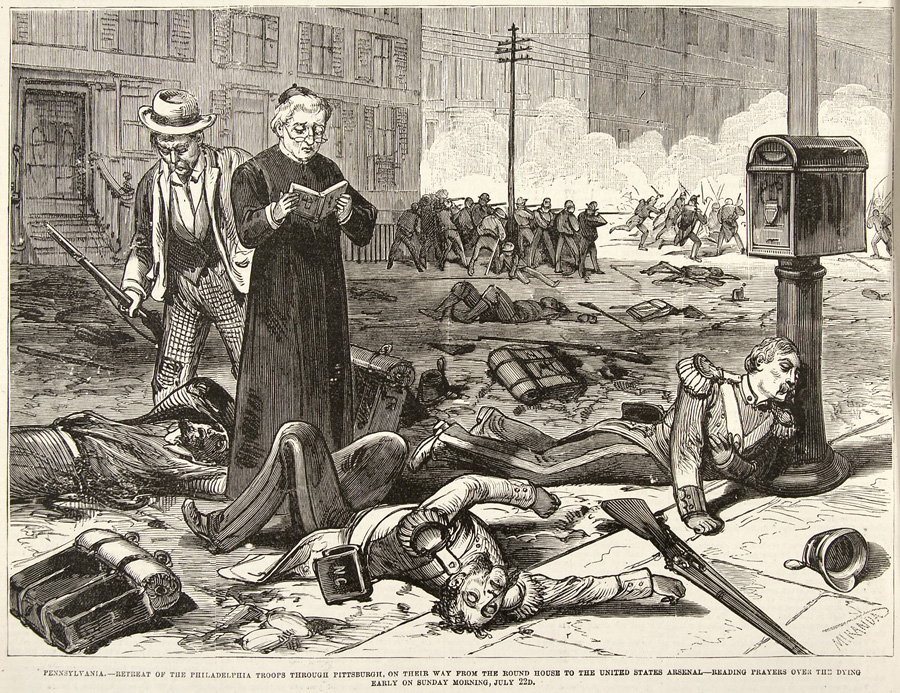

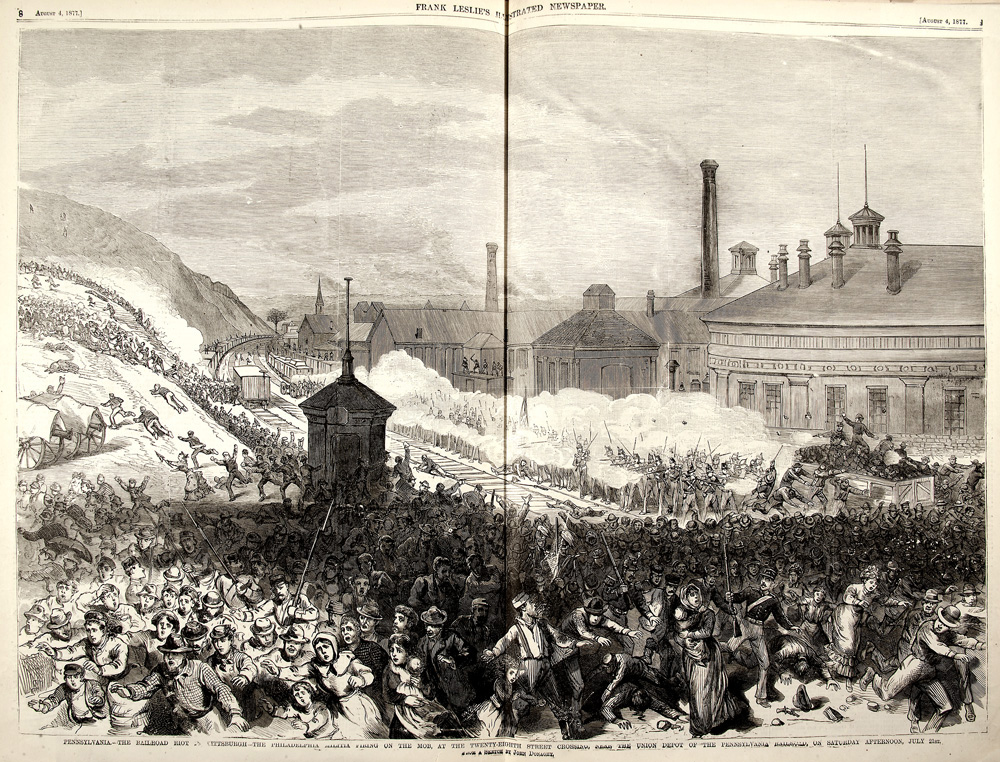

Pittsburgh witnessed some of the most extreme violence. Here, fury at the Pennsylvania Railroad (which announced a 10% wage cut in June) and local sympathy for the strikers prompted state officials to send in a Philadelphia-based militia force. On July 21, as these troops faced a crowd that had gathered around the 28th street crossing near Liberty Ave., pistol shots rang out. To this day, no one is sure who fired first. In response, the militia shot into the crowd, killing more than 20 people.

Stunned strikers and onlookers dispersed, but the act ultimately ignited a fiery riot. By that evening and through July 22, thousands of people flooded city streets, clashing with the militia and each other. Fire destroyed more than 30 buildings, including the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Union Depot, and thousands of pieces of rolling stock, including locomotive engines and rail cars. Cannons were placed on bridges into Allegheny City to prevent the angry mob from crossing. By the time the violence began to subside, a large section of Pittsburgh lay in ruins.

S.V. Albee recorded this aftermath, composing images that emphasized the scale of the destruction. He took more than forty photographs for stereograph cards, a popular 19th century parlor amusement that allowed people to see three-dimensional views of famous scenes. That people might be interested in such images can be seen in the cards themselves, which capture onlookers strolling amid the ruins.

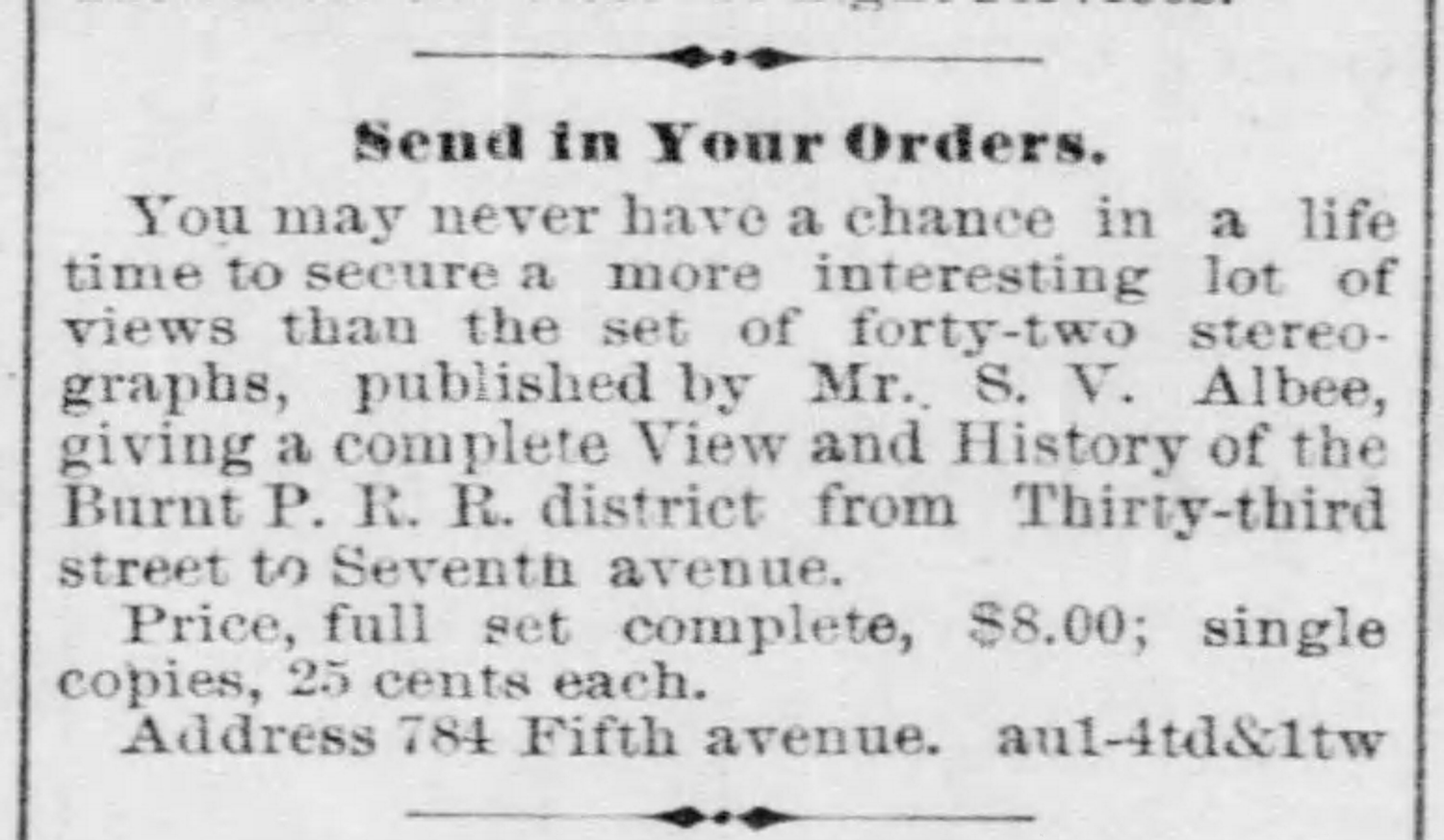

Albee acted quickly. By Aug. 2, 1877, he was advertising in the Pittsburgh Daily Post, announcing, “You may never have a chance in a lifetime to secure a more interesting set of views.” He titled his set “The Railroad War.” Albee wasn’t alone. J. R. Riddle, a photographer from Fairview in Butler County, also took views of “Pittsburgh in Ruins,” although fewer of his works survive. (Riddle, who spent time photographing the Pennsylvania oil fields, eventually left for Colorado.)

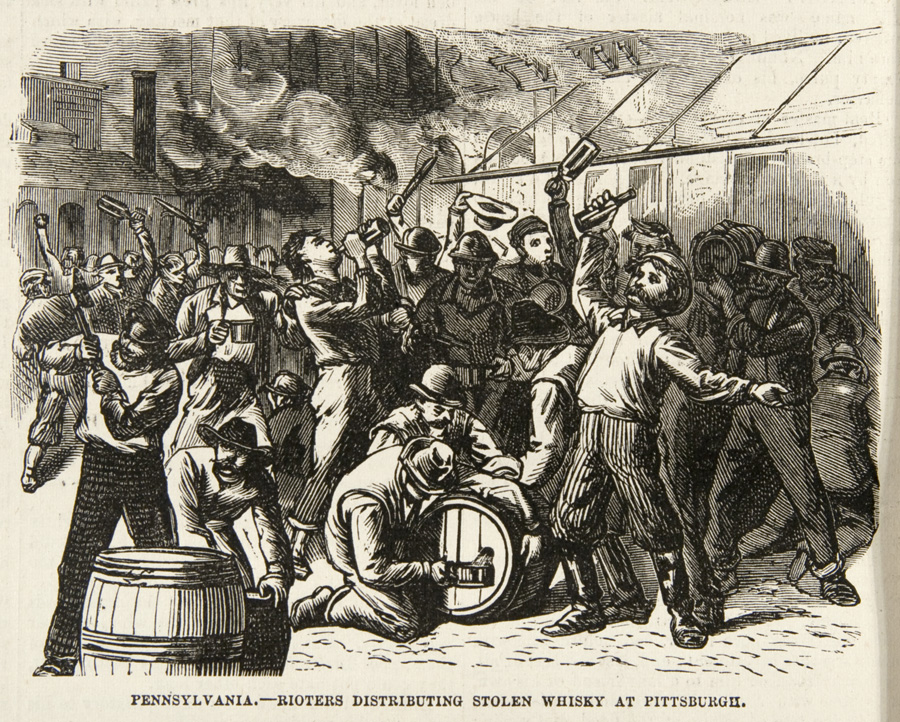

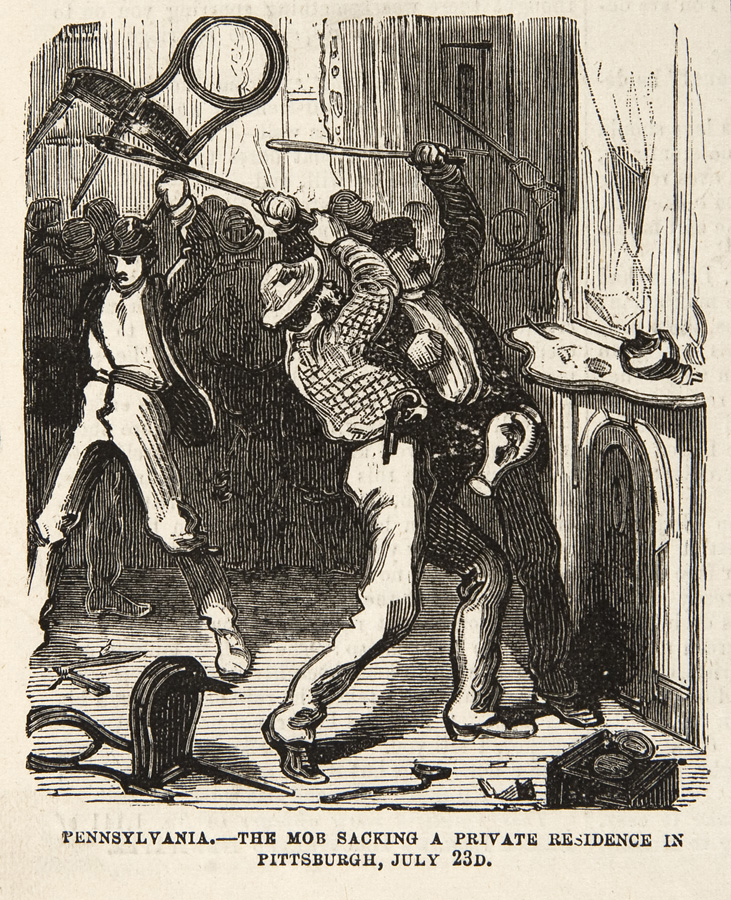

The stereograph views differed from other visual media of the day. Disaster prints and newspaper engravings, such as those in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, focused on dramatic action, often with creative license thrown in. Commissioning local artists to do sketches that were transformed into engravings, newspapers wanted moments of high emotion: militia soldiers lying dead in city streets, a crowd helping itself to looted whiskey or sacking a private home, people fleeing from gunfire. These images sold papers to a national audience that eagerly consumed the “you are there” drama, reinforcing the sense of “riot” that shaped public memory of the event for generations.

General Photographic Collection, Senator John Heinz History Center.

Instead, Albee and Riddle captured the impact of what was left behind: a massive cleanup that the Pennsylvania Railroad estimated would cost Allegheny County more than four million dollars. (The county eventually paid about 2.6 million, an equivalent of at least 55 million today.)

While film of the day was too slow to capture the action shown in illustrations, Albee and Riddle may have had other reasons for focusing on what they did. Both specialized in industrial photography. Albee advertised as a “Practical Business Photographer,” someone skilled in capturing “Architectural and Mechanical images,” including photographs of public buildings, bridges, tunnels and local industries. Business leaders were his clients. Memorializing the strike’s aftermath created a record that mattered to them as more than mere curiosity. Even Albee’s title for the series – the “Railroad War” rather than the “Railroad Riot” – conveys a certain perspective. A “war” is a conflict involving two sides; Albee is speaking to an audience. His pricing of the set also placed it above the means of the average worker. Albee originally advertised the full series for eight dollars, a large sum in a day when the average laborer made far less than three dollars a day; he later reduced it to six dollars. Curious collectors of less means could purchase individual cards for a quarter.

Today, Albee’s stereographs stand as unique documentation of a key historic event, but they also remind us that photographs are not objective images. They are guided by the motives of the person behind the lens.

For Further Reading

There are many sources today that deal with story of the Railroad Strike of 1877. Here are a few good ones to get started.

Perry K. Blatz, “Pittsburgh, The Fiery Scape Goat for the Country,” Western Pennsylvania History, Fall 2011: pp 46-61.

Zach Brodt, 1877 Railroad Riot, Archives Service Center @ Pitt blogpost, August 17, 2015.

Patrick Grubbs, Railroad Strike of 1877, The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, Rutgers University, 2016.

Railroad Strike of 1877 Historical Marker, Explore PAhistory.com, 2011.

The 1877 Railroad Strike, Railroads and the Making of Modern America. University of Nebraska – Lincoln, ©2006-2017.

Leslie Przybylek is curator of history at the Heinz History Center.