A young adventurer from Pittsburgh defied odds and changed aviation forever after completing the world’s first transcontinental flight in 1911.

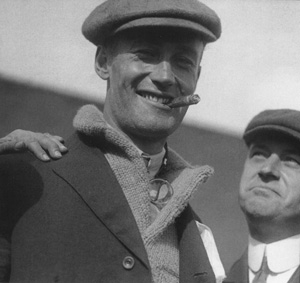

Calbraith Perry Rodgers Jr. was born in Pittsburgh on Jan. 12, 1879 to a family with a long history of prestigious U.S. Navy service. Rodgers was related to Commodores John Rodgers (grand-uncle), Oliver Hazard Perry (great-grand-uncle), Matthew Calbraith Perry (great-grandfather) and a cousin to John Rodgers, a Naval Aviation pioneer known for establishing the record of longest non-stop flight by seaplane of 1,992 miles on an attempt to fly from San Francisco to Honolulu in 1925.

Named after his father, an army captain who died in Wyoming Territory five months before his birth, Rodgers grew up in an affluent household in the Shadyside neighborhood of Pittsburgh with his mother Maria Chambers and grandparents. He frequently spent his summers on the Rodgers’ family estate in Havre de Grace, Md.

A childhood battle with scarlet fever left him partially deaf and ineligible for military service. Refusing to let his deafness inhibit his desire for adventure, Rodgers spent his young adulthood sailing and racing horses and cars.

In the spring of 1911, at the age of 33, Rodgers found his calling when he traveled to Dayton, Ohio, with a cousin who had been stationed there for flight training. Rodgers visited the Wright Flying School, operated by famous aviation pioneers and brothers, Orville and Wilbur Wright. There, he saw an airplane for the first time and became fascinated with the idea of flying.

Just one week after Rodgers began taking classes at the school, he requested permission to take a solo flight, but he was denied due to lack of training. Rodgers responded by purchasing his own training plane, and on June 12, 1911, he made his first solo flight. After practicing with his plane for just over a month, Rodgers passed the Federation Aeronautique Internationale’s flying examination on Aug. 7, becoming the 49th licensed aviator in the world.

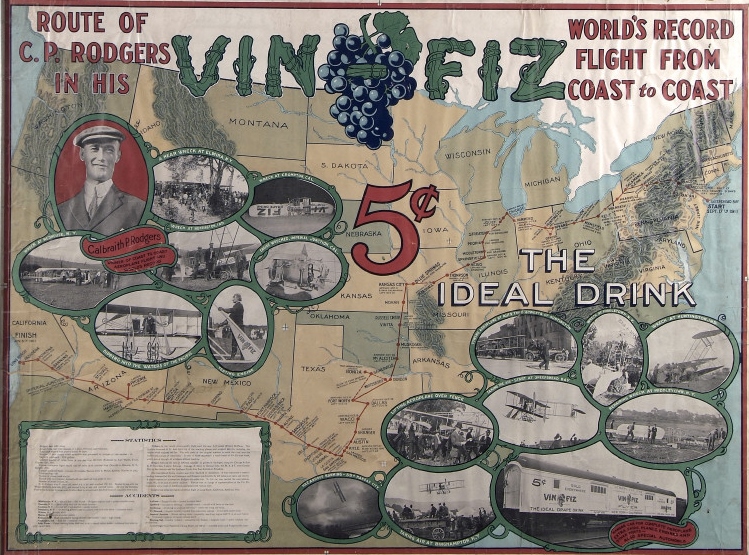

Less than a week later, while participating in a Chicago air show, a promoter asked Rodgers if he would be interested in competing for the Hearst Prize. Publisher William Randolph Hearst had recently offered $50,000 to the first person who flew from coast to coast in fewer than 30 days. Rodgers accepted the challenge.

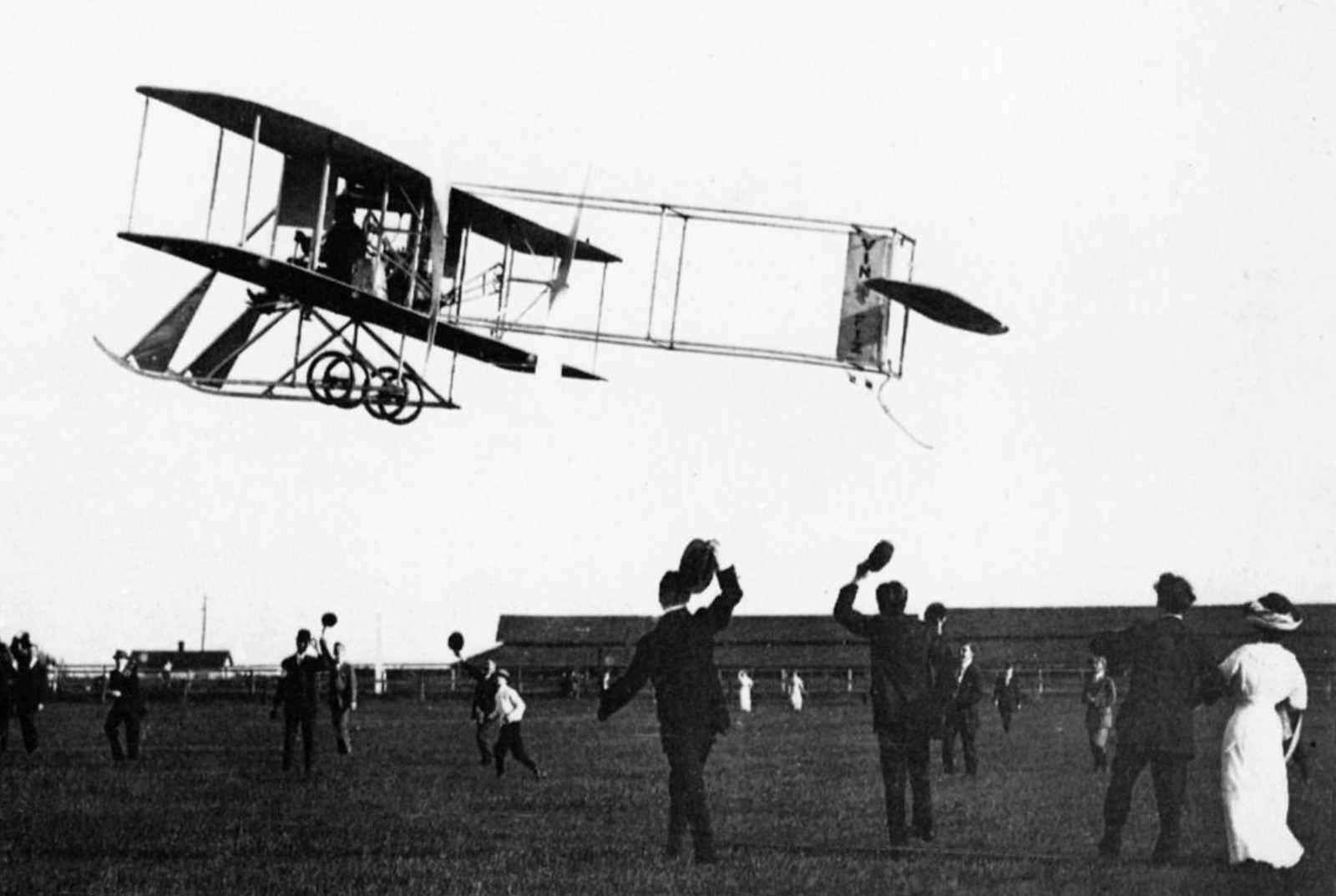

On Sept. 10, Rodgers purchased a lightweight, four-cylinder, 35-horsepower Model EX biplane from the Wright Company. When he purchased the plane, Rodgers told Orville Wright of his plan to compete for the Hearst Prize. Wright, doubting any modern plane’s ability to travel so far, questioned Rodgers’ decision. An adventurer and risk-taker, Rodgers paid no attention to Wright’s warning. He secured sponsorship for his adventure from Armour Meat-Packing Co., which was promoting its new grape soda, Vin Fiz, the namesake of Rodgers’ plane.

Seven days after purchasing his new plane and just three months after learning how to fly, Rodgers took off from Sheepshead Bay in Long Island, N.Y., on Sept. 17, 1911, poised to reach the Pacific Ocean in 30 days. A support train followed Rodgers’ flight, carrying all the parts, tools, and mechanics necessary for repairs and maintenance.

After first landing in Middletown, N.Y., without incident, the Vin Fiz crashed and suffered extensive damage during take-off the next day. More incidents, including two engine explosions, more than 15 crashes, and as many as 70 rough landings, significantly delayed Rodgers. In addition to the maintenance-related delays, Rodgers lacked navigation tools (he didn’t even have a compass!) and as a result, he got off-track on multiple occasions.

Without reliable weather forecasting techniques and with impaired hearing, Rodgers was unable to make informed decisions about the safest times for takeoffs and landings. By the time Rodgers reached Chicago on Oct. 8, it was clear he would not be able to complete the journey in 30 days. Rodgers, who remained determined to finish the trip anyway, became incredibly popular with the American public, as evidenced by the crowd of 20,000 waiting for him in Pasadena, Calif., when he landed there on Nov. 5, 1911.

Finally, on Dec. 10, 1911, he landed in Long Beach, Calif., and taxied his plane into the Pacific Ocean, completing the world’s first transcontinental flight. The cross-country trip took 49 days to complete, missing the prize deadline by 19 days. While the feat made Rodgers an instant national celebrity, his success was short-lived, as he was killed in a plane crash after flying into a flock of birds just a few months later at an air show in California.

Following his death, Rodgers was interred in Allegheny Cemetery in Pittsburgh. The Vin Fiz itself was later given to the Smithsonian Institution by Calbraith’s widow, Mabel Rodgers. Visitors to the Heinz History Center can see a replica of Rodgers’ Vin Fiz airplane as part of the Pittsburgh: A Tradition of Innovation exhibition.

Lauren Ball is an intern volunteer with the communications division at the Heinz History Center.