Some foods just go well with beer. Of all the bar treats linked to the rise and fall of the American saloon, none played so public a role as the pretzel. In honor of National Pretzel Day, here’s a look back at how the pretzel became a player in the drama that led to Prohibition.

The Origin of the Pretzel

The pretzel’s real origins are as tangled as its shape. Legend traces it to medieval Europe, where Italian monks reportedly created treats to reward schoolchildren by baking dough with arms shaped in prayer. The tradition spread through Europe, and pretzels became associated with good luck and eternal love. By the 1600s, countries such as Switzerland reportedly used pretzels in wedding ceremonies to symbolize the matrimonial bond, or “tying the knot.” Rumor has it that the Pilgrims brought pretzels with them on the Mayflower. (They needed something to go with the beer they carried as well.)

No ethnic group was more associated with pretzels than the Germans. This connection entered Pennsylvania history when German immigrants brought pretzels with them to the colony in the 1700s. While most early pretzels were of the soft variety, a German baker in Lititz, Pa., Julius Sturgis, reportedly started the first commercial pretzel bakery in 1861 and claimed credit as the creator of the first true hard pretzels.

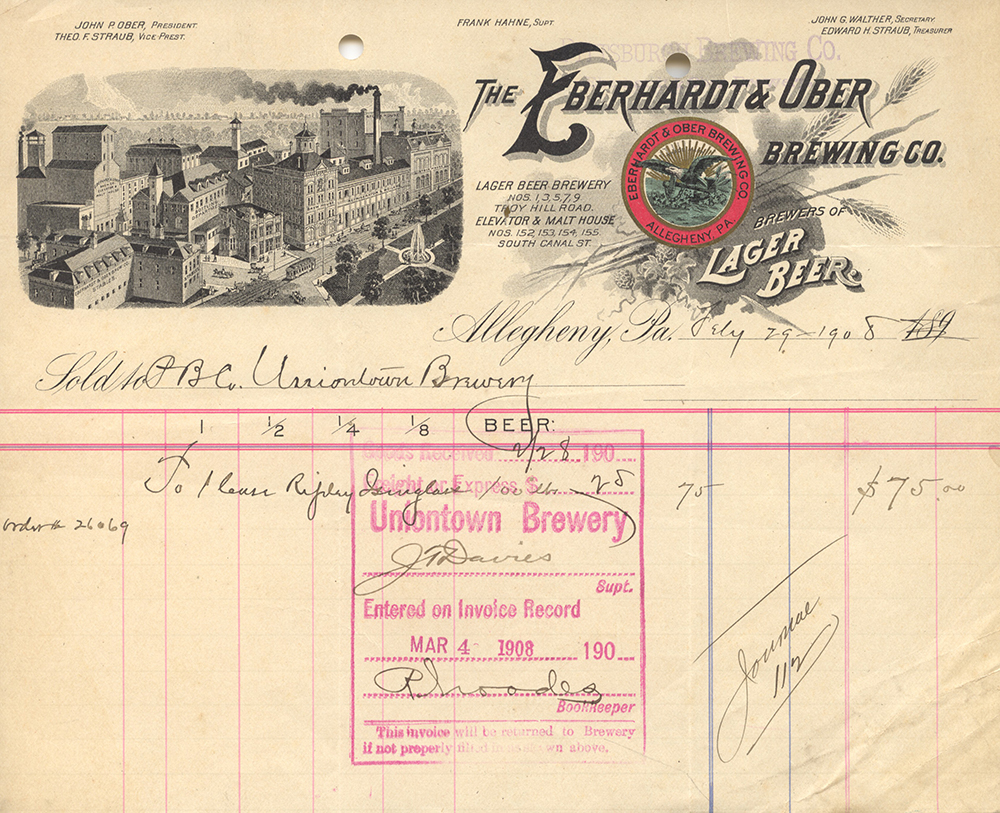

Whatever their origin, hard pretzels arrived just in time for the rise of the saloon after the Civil War. In contrast to taverns, the male-only saloon focused on drinking rather than eating. As large brewery cooperatives began sending their beer beyond local neighborhoods, the saloon proved to be the perfect sales outlet. Large breweries supplied potential saloon operators with everything they needed to go into business, with one catch: they could only sell that brewery’s beer. By the 1870s, the number of saloons exploded as breweries competed to saturate the market with their own products. Who dominated this world of American brewing? German immigrants and their families.

The Perfect Bar Snack

While most saloons did not offer a full menu, proprietors recognized that customers would stay and drink if they could eat something, especially something salty that inspired a greater thirst for the “golden suds.” The German hard pretzel—economical, salty, easy to pack, ship, store, and serve—was the perfect bar food. In some cities, a majority of the pretzel trade was sold directly to saloons, which could go through as many as two or three barrels of pretzels a week.

So completely intertwined were the images of the German brewer and the German pretzel—sometimes referred to as the “German biscuit”—that the two were often pictured together. By the early 1900s, the Pittsburgh Daily Post regularly ran humorous illustrations that combined the distinctive form of the pretzel and the traditional costume of ethnic Pennsylvania Germans.

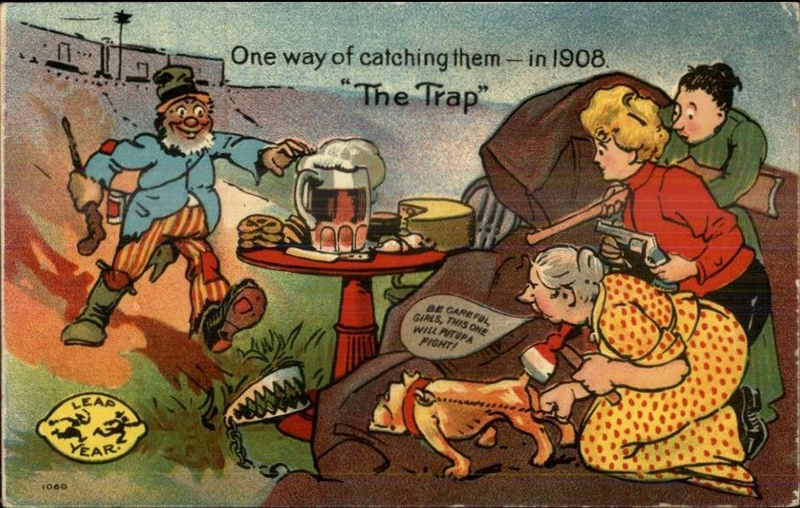

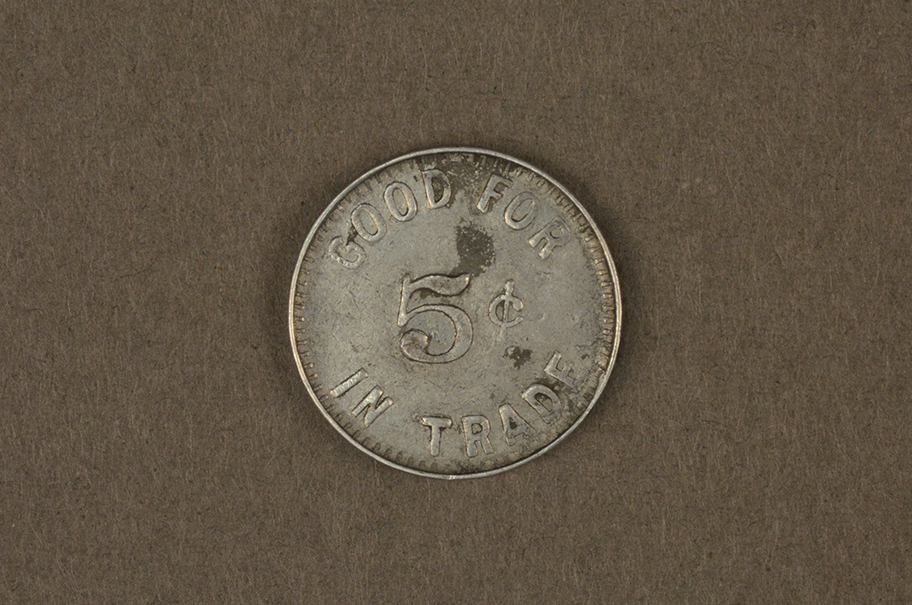

But the pretzel’s barroom popularity also put it in the middle of debates over the use and impact of these spaces. As competition increased, many saloons started offering something called the “free lunch” – a hearty communal table set with a variety of items such as soup and stew, meat, bread, crackers, pickles, relishes, cheese, and yes, pretzels, all “free” to patrons with the purchase of a drink or two (or more). Sometimes, the cost was one “nickel beer.” Effectively underwritten by the breweries, five cents bought a drink and a meal that was cheaper than what restaurants could offer. The practice infuriated saloon critics, who saw it as one more tactic to separate workingmen from their paychecks and their families.

As Pittsburgh and other cities waged war against the free lunch, the pretzel bounced in and out of respectability. In Pittsburgh, the License Court banned pretzels on multiple occasions along with the rest of the free lunch, but each time granted them a reprieve to join cheese and crackers at the bar. “Pretzels are Permitted,” proclaimed a Pittsburgh Press article in May 1909, acknowledging that License Court officials had decided after a challenge from local attorneys that pretzels were “practically the same thing” as crackers.[1]

The Pretzel’s Fate

The biggest hurdle arrived in 1917-1918, when World War I fueled anti-German sentiment in the United States. As Prohibition’s advocates used this public antipathy to build support for the 18th Amendment, German foods also became targets. By 1918, even the Los Angeles Times declared that the pretzel was “too German to be taken seriously.”[2] Pretzels were again banished from the barroom. This time, the embargo became permanent when Prohibition was ratified in 1919 and the fate of the saloon was sealed.

For a while, the future of the pretzel was in question. “Pretzel Business on the Bum,” the Pittsburgh Press announced in September 1923, noting that the city’s “Sahara-like” dryness under the Volstead act (a reference partly in jest) created a challenging environment for the formerly “happy couple” of pretzels and beer. Eating pretzels with “near beer” the paper reported, left an undesirable taste compared to the “delicacy” of the old days.[3] At least one enterprising pharmacist in Ellwood City tried to convince people that the combination of pretzels and buttermilk was just as appealing.[4]

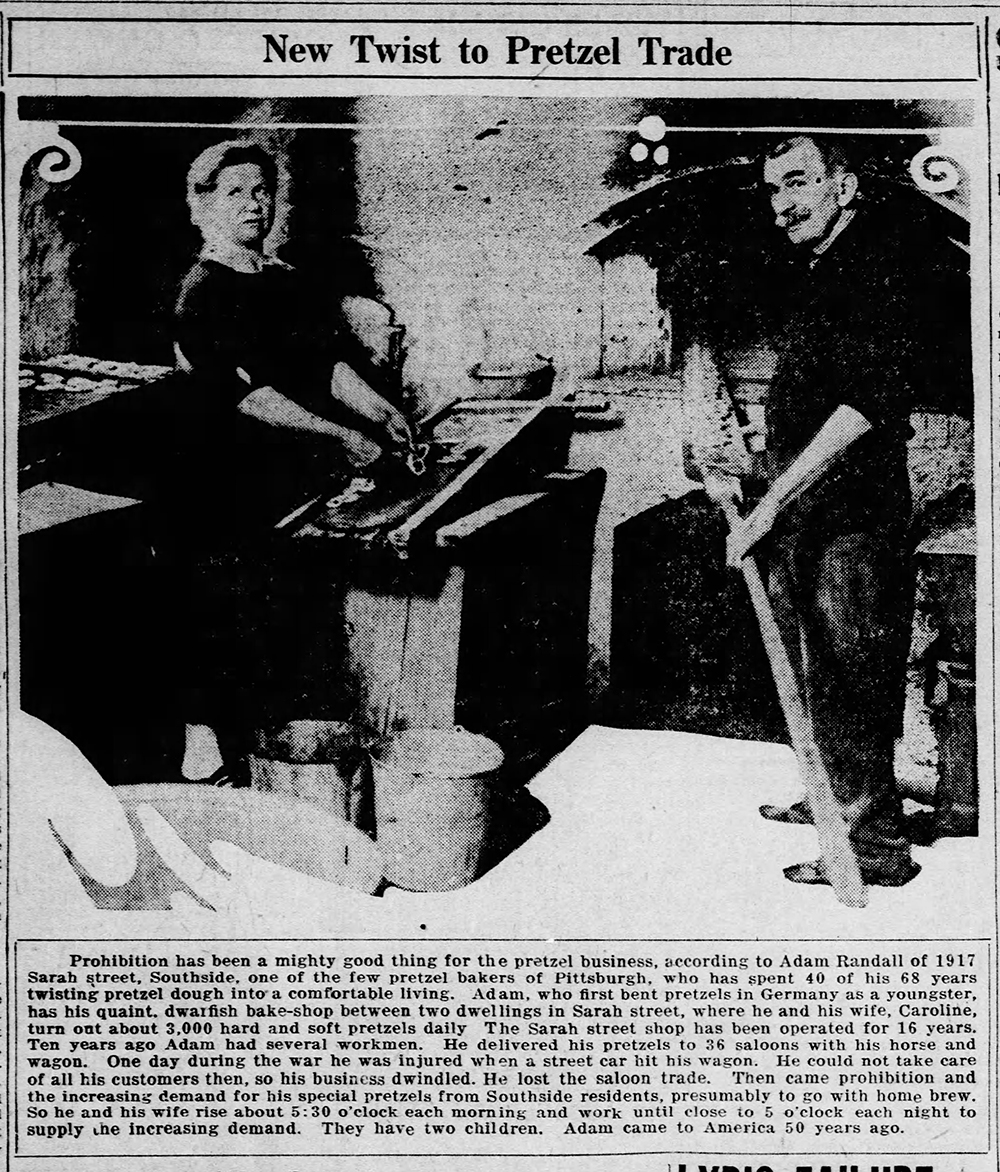

In the long run, the pretzel not only survived Prohibition, it thrived. One pretzel maker found that the trade from his small Sarah Street bakery increased after 1920; he surmised that people were buying pretzels to go with their home brew.[5] Pittsburgh’s largest pretzel manufacturer of the time, H. B. McNeal, also reported increased sales. The pretzel as a snack independent of beer grew so popular that some manufactures began abandoning the traditional curved shape for the pretzel stick, which was easier and faster to produce at a time when all pretzels were still made by hand. [6]

By the time the Reading (Pa.) Pretzel Machinery Company introduced the first automated pretzel maker in 1935, the tasty snack had become an indelible part of Pennsylvania’s food heritage and a symbol of the state’s German ancestry. Today, roughly 80 percent of the pretzels sold nationwide are still made in Pennsylvania.

Learn more about the history of America’s experiment with Prohibition now through June 10, 2018 in the American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition exhibition.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.

[1] “Pretzels Are Permitted,” The Pittsburgh Press, May 7, 1909.

[2] “The Pretzel’s Passing,” Los Angeles Times, April 19, 1918.

[3] “Pretzel Business on the Bum, Ruined In Fact, As Sahara-Like Dryness Clamps Pittsburgh’s Former ‘Growler Rushers’ In Death Grip,” The Pittsburgh Press, September 14, 1923.

[4] “Buttermilk is Great Favor,” New Castle Herald, March 25, 1919.

[5] “New Twist to Pretzel Trade,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 25, 1927.

[6] “Curved Pretzel Threatens to Become Extinct Soon,” The Pittsburgh Press, June 16, 1927.