As the History Center explores the theme of resilience as part of its “History’s Helpers” initiative, it is a good time to revisit an event that has been discussed here before. Pittsburgh’s Suffrage Shirtwaist Ball, held on Nov. 10, 1916, remains a popular topic, especially as we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. You can read the original story about this unique suffrage fundraiser on our blog.

While the Shirtwaist Ball’s basic story has been told, examining it more closely within the context of the suffrage movement and anti-suffrage imagery underlines the resilience of the Pennsylvania women who sponsored it and who fought so long and creatively for women’s right to vote. The ball was more than a fundraiser: it was a lobbying action that took place a little over a year after one of the Pennsylvania suffragists’ most disappointing defeats. The symbolism of the “shirtwaist” and the playful humor conveyed by the ball responded to how suffrage had been depicted in popular media for more than 80 years. In many ways, the event gave its supporters the emotional boost they needed, encouraging them to look forward just when it might have been tempting to dwell on the past.

The Legacy of 1915

The Suffrage Shirtwaist Ball took place a little more than a year after Pennsylvania suffragists watched their campaign for the ratification of a state amendment supporting women’s right to vote go down in defeat in early November 1915. The loss was especially hard because the situation seemed so promising. The barnstorming tour of the “Justice Bell” — a replica Liberty Bell that would not ring until women won the right to vote — had taken the cause to each of the state’s 67 counties. Supportive crowds of men as well as women gathered at every stop. Victory was in the air.

But when the final votes were tallied, strong anti-suffrage sentiment in portions of the state’s two largest cities gave the victory to the “No” faction. While the margin of loss, between 125,000 and 150,000 votes, was deemed surprisingly small by the local press and gave women reason to hope, it still must have been a blow. As they had done before, supporters rallied and kept going. Many assembled in Philadelphia at the end of that month for the annual convention of the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association (PWSA). Just imagine the conversations that must have taken place. Among the Pittsburgh delegates attending was Winifred Meek Morris, who in 1916 served as the general chairman of the Suffrage Shirtwaist Ball.

Another Year, A New Strategy

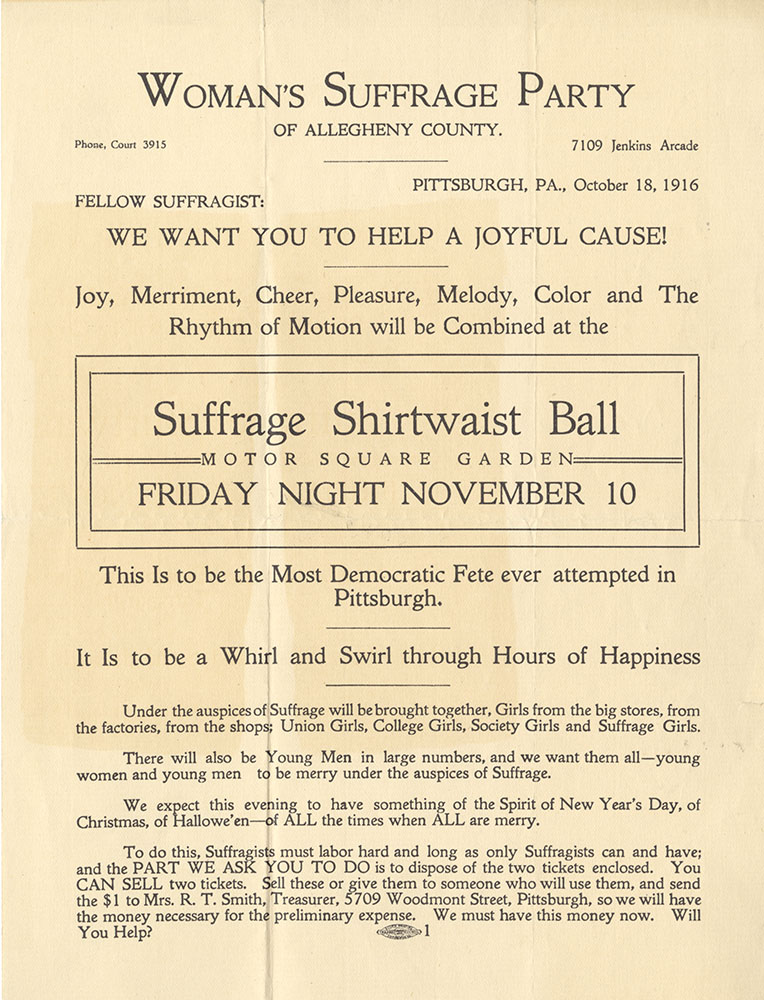

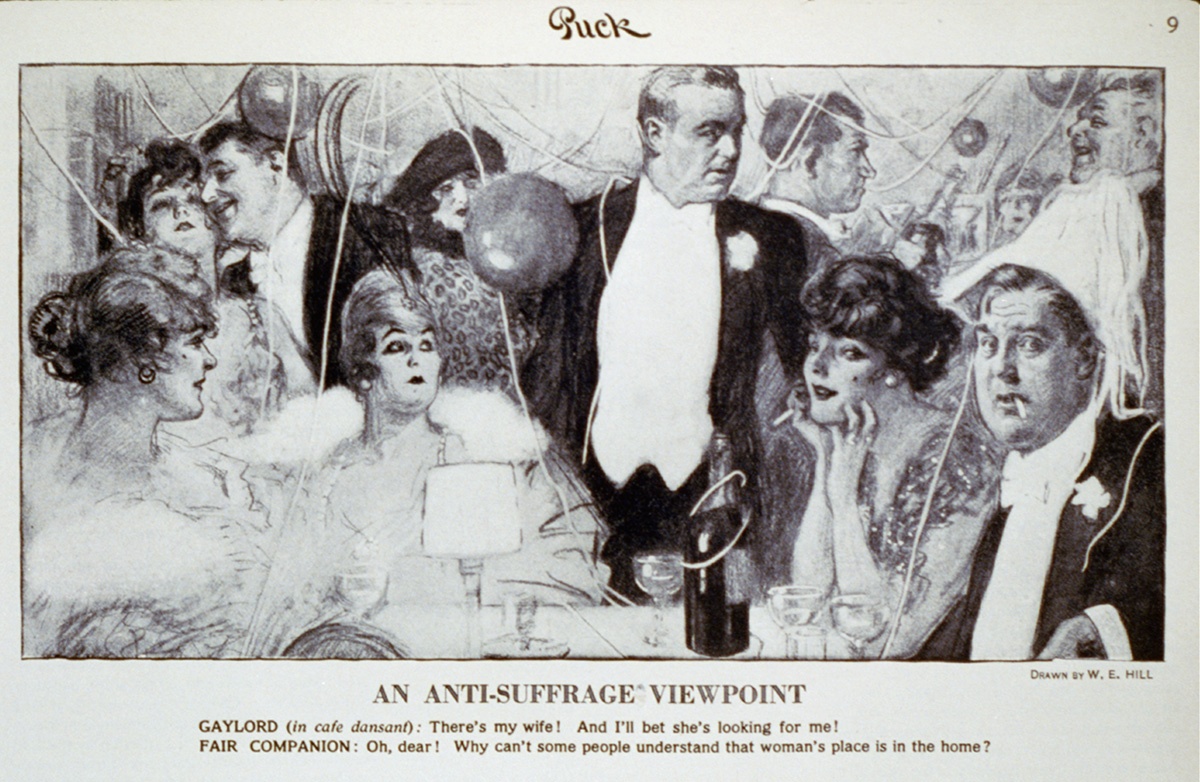

As another year rolled around, Pittsburgh’s Equal Franchise Federation, an auxiliary of the statewide PWSA, announced the Suffrage Shirtwaist Ball in November 1916 as their main fundraising event, exhorting fellow suffragists to “help a joyful cause.” In contrast to the urgent political effort in 1915, at first images of the Shirtwaist Ball seem frivolous by comparison. The ball’s poster, featuring two of the suffrage campaign’s key colors – yellow and white – shows a young woman in a flowing dress, complete with a strategically placed keystone at her waist, dancing with an older gentleman. She looks knowingly at the viewer. The poster slogan, “Her Hope, His Opportunity,” functions as a double entendre. The image plays on visual conventions found in humor magazines of the time, which sometimes used society dances and social events to comment upon the suffrage debate. See, for example, an illustration titled “An Anti-Suffrage Viewpoint” from the humor magazine Puck in 1915. An older gentleman, out with some younger female companions, searches for his wife in the crowd. The phrase “A women’s place should be in the home,” addresses the idea that his wife should stay far away from his extracurricular night on the town. Other images characterized society women as too immersed in their own social activities to be concerned with voting.

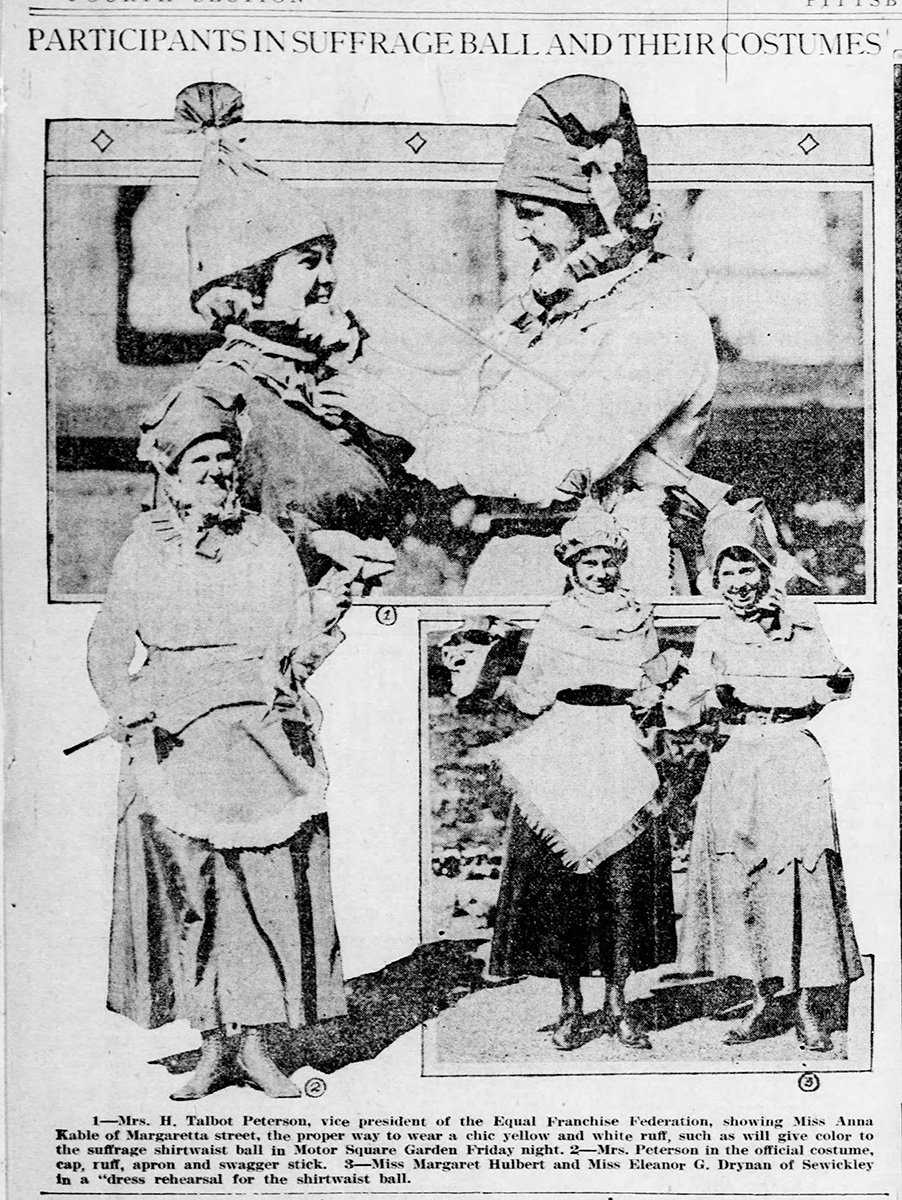

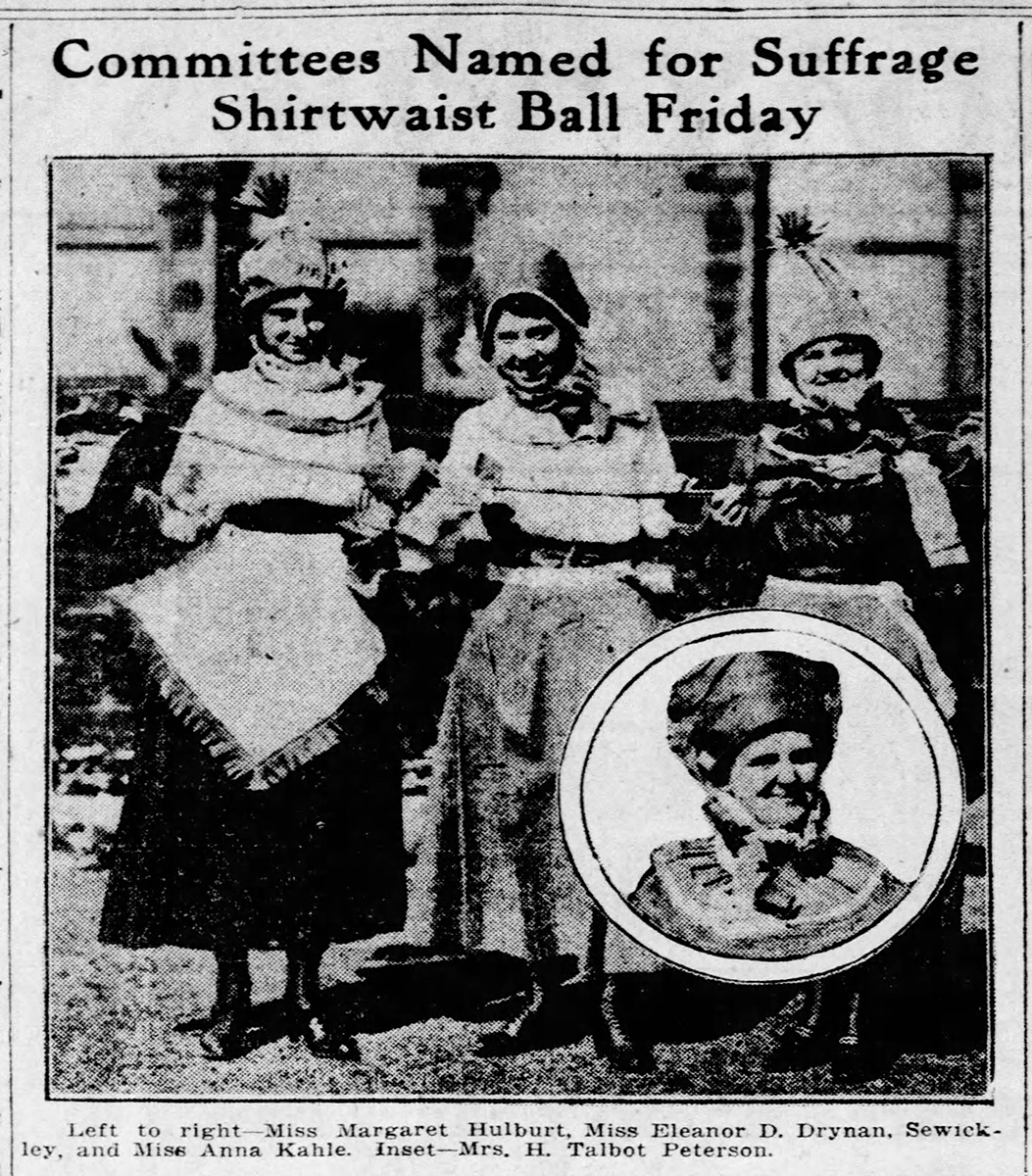

That the Shirtwaist Ball poster image was presented with tongue in cheek is also suggested by promotional news photos of the actual plans for the dance that appeared in local papers. Emphasizing yellow as the color of the evening, young women modeled the anticipated party favors, including yellow paper party hats, yellow aprons, yellow and white neck ruffs, and yellow swagger sticks (like riding crops). Resembling elements of a comic masquerade rather than a society swirl, these images create a distinctly different picture of the event. The flyer for the ball described it as a mix of New Year’s Day, Christmas, and Halloween.

Shirtwaist Symbolism

The idea of a shirtwaist ball was not new. That was part of the point. The concept for a less formal, more welcoming social affair emerged in the late 1890s, as the “shirtwaist” gained popularity as a type of women’s clothing. Modeled after menswear, the more casual, often ready-to-wear women’s blouse first appeared in the late 1800s. Along with convenience and flexibility, it came to symbolize the growing class of women factory and clerical workers. The shirtwaist stood for working women and new ideas about women’s role outside the home. By 1916, this was further complicated by events such as the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City in 1911, a tragedy that underlined the need for women to have a voice in modern American society. When the flyer for Pittsburgh’s Suffrage Shirtwaist Ball listed the women who would be brought together — “girls from the big stores (e.g. department stores), girls from the factories, from the shops”— it acknowledged this context.

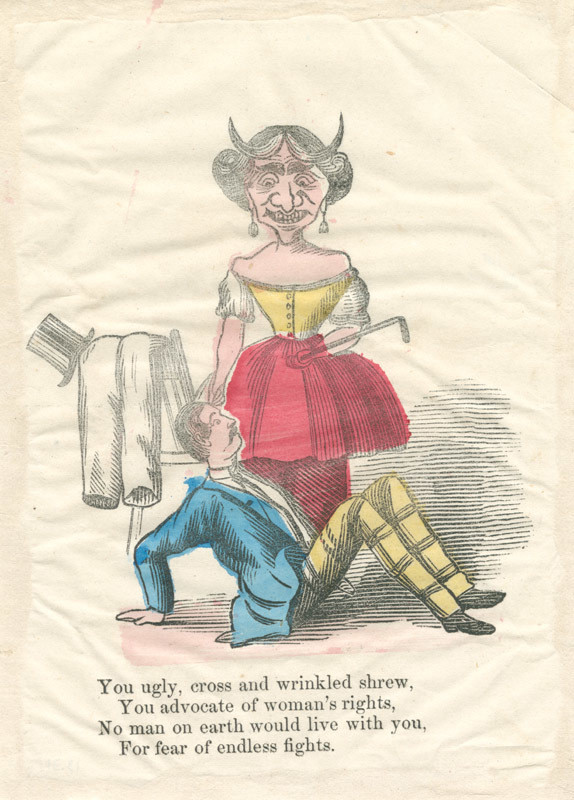

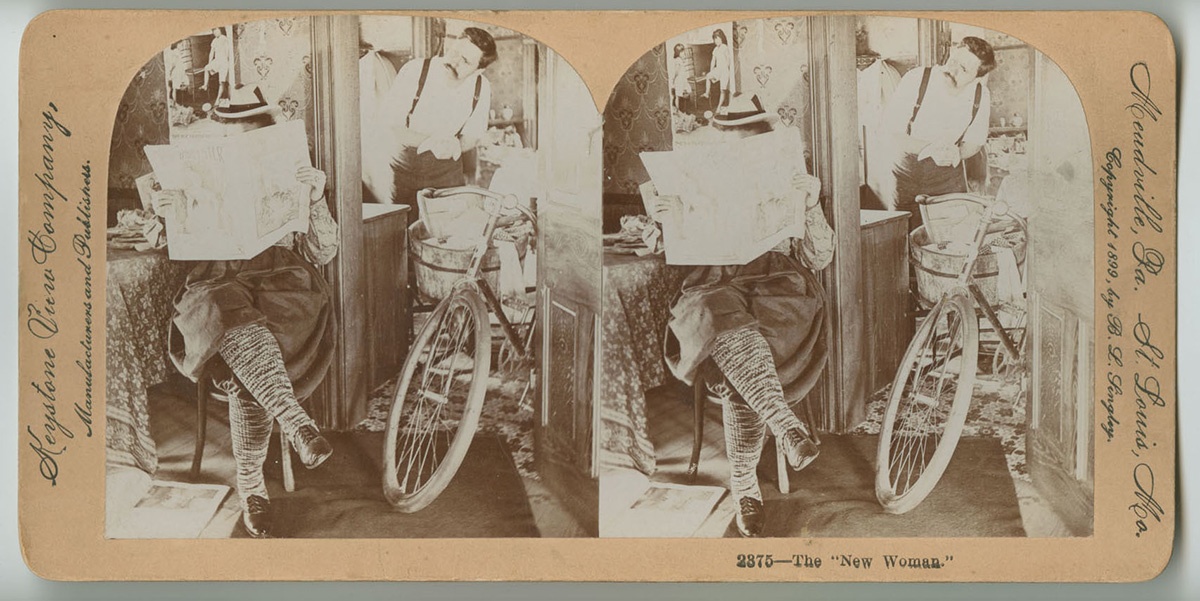

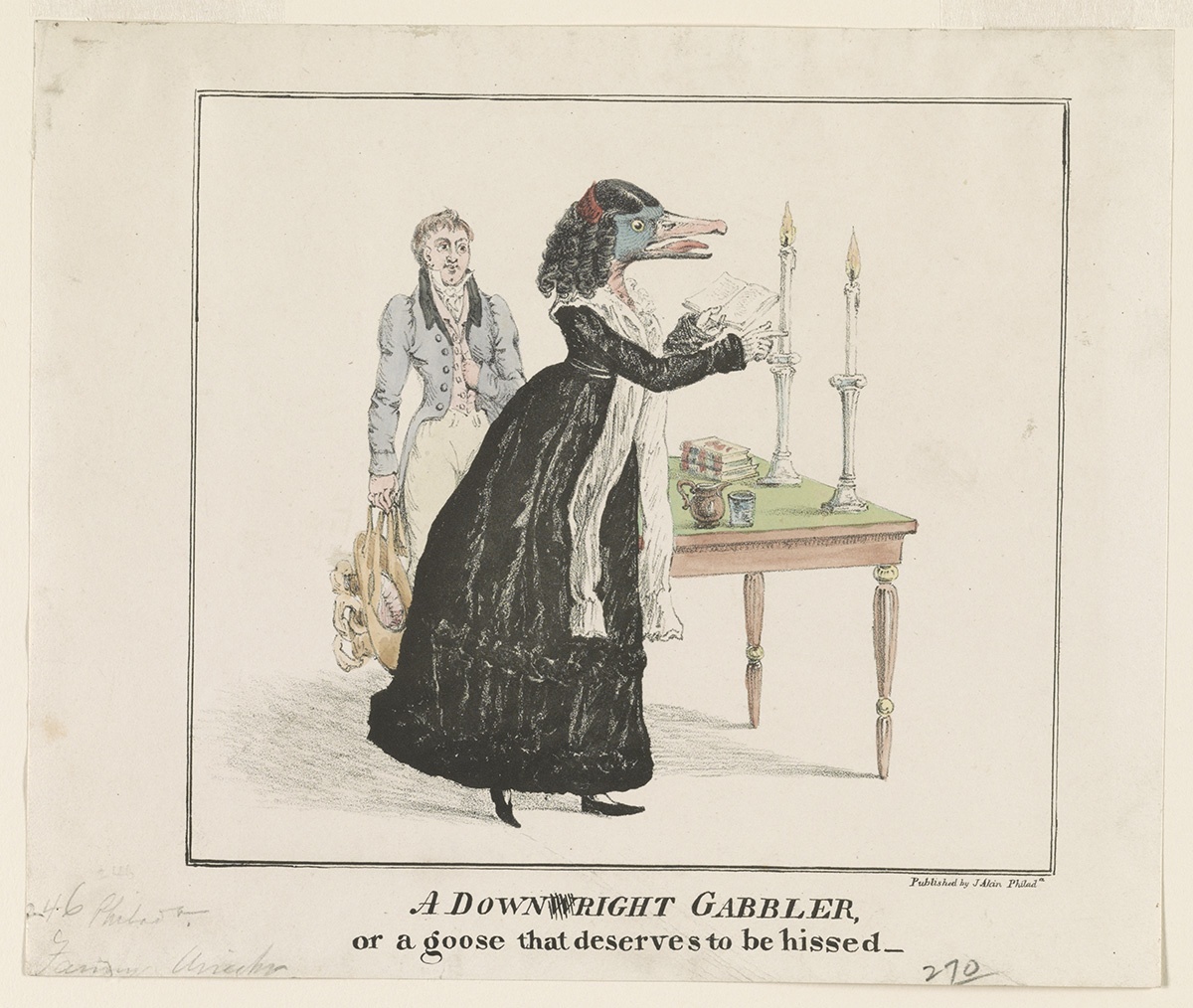

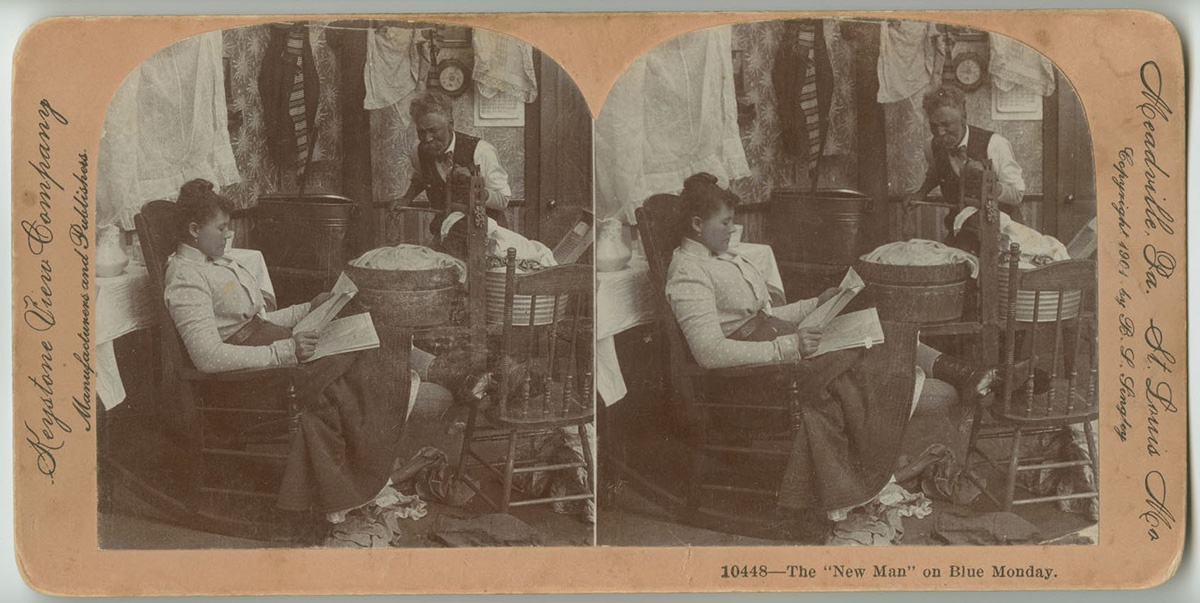

The image of the shirtwaist-wearing woman also appeared in popular amusements of the day. It was part of the “New Woman” figure glamorized by artists such as Charles Dana Gibson and treated in less celebratory fashion on mass-produced novelties such as stereoview cards. This was only the latest chapter in a long visual tradition depicting women’s suffrage advocates as “gabblers” and transgressive shrews. When women advocated for the right to vote, both their goal and how they fought for it violated the bounds of what some people deemed acceptable behavior. The stereotyped images generated by anti-suffrage proponents in response could be downright vicious. Women fought against this vision for decades on the path to securing the vote.

The organizers of Pittsburgh’s Suffrage Shirtwaist Ball brilliantly played against these cultural currents in creating an event that brought as many supporters as possible under one roof. Never taking “no” for an answer, they kept finding new ways to argue their case. In that sense, their fundraising ball exemplified their collective resilience and their belief that if they kept on fighting, surely someday they would prevail.

More

Thank you to the Library Company of Philadelphia, Print Department, for the use of several images in this blog post.

Read the original Making History blog post, At the Shirtwaist Ball, and see archival materials from the collection of Winnifred Meek Morris.

For more information about Pennsylvania’s Justice Bell campaign in 1915, check out this post on the site of the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities.

For more information about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, check out this site on the fire and its public memory from Cornell University.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.