The largest cannon of the Civil War was a monstrous 20-inch caliber ship killer designed by Thomas Jackson Rodman—one of America’s most innovative and productive ordnance experts. Cast at Pittsburgh’s Fort Pitt Foundry in 1864, Rodman’s Columbiad was a marvel of military engineering and epitomized the prodigious power of the Iron City’s industry. The genesis of Rodman’s big gun and the new generation of armament it inspired began well before the Civil War, but when the nation celebrated its centennial in 1876, the hollow-cast, internally cooled, 20-inch Rodman gun was still a military engineering marvel that captured the attention of millions of spectators that attended the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

On August 14, 1847, Rodman was awarded Patent No. 5,236. Pittsburgh had already gained a reputation as the “Iron City” and by 1849 he worked out a partnership with receptive iron founders Charles Knap and William Totten. Rodman assigned his patent to the Fort Pitt Foundry owners, and in exchange they funded the research and development and agreed to pay him 1/2 cent per pound for every finished cannon cast using his system. The Fort Pitt Foundry, located just two miles from Allegheny Arsenal, cast Rodman’s guns and cooled them by pumping air then water through a hollow core, making the finished guns better able to withstand the tremendous pressures exerted by hundreds of pounds of burning gunpowder pushing cannon balls weighing over 1,000 pounds out the barrel at velocities in exceeding 1,700 feet per second. Rodman also eliminated any reinforces or other abrupt changes in the gun’s exterior contours. He had discovered that cracks and failure usually occurred at these places, and his cannons now took on the smooth “soda bottle” shape that became their most distinguishing characteristic.

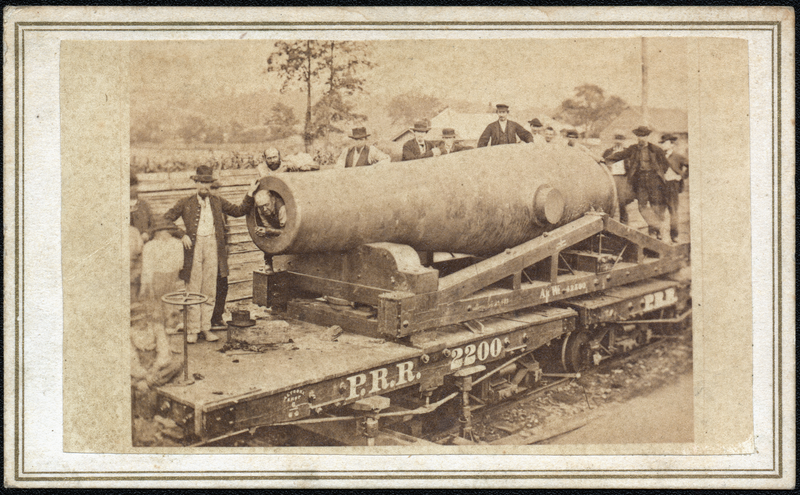

The 20-inch Rodman gun required special handling to get it to Brooklyn’s Fort Hamilton at the Narrows that separated New York’s upper and lower bay. Twenty-four big horses and a small army of foundry workers hauled, levered, and wheeled the massive barrel to a railroad spur where two specially fitted flatcars with double trucks (iron wheels) waited. While the special cars would help distribute the gun’s tremendous weight, Pennsylvania Railroad officials carefully inspected rails and ballast between Pittsburgh and New York and shored up or otherwise strengthened the trestles and bridges along the route to ensure that they could accommodate the unusual load. Even with these precautions, the journey took nearly a month as railroad officials limited the speed to a crawl in order to avoid excessive friction on bearings, wheels, and rails.

Once Rodman had demonstrated that the gigantic gun was a practical reality, the country seemed to lose interest. The very fact of its menacing existence apparently satisfied the President and the Ordnance Department. Further testing was not carried out until 1867. When loaded with 200-pounds of Rodman’s improved cake powder, the half-ton ball flew nearly five miles. One well-aimed shot obliterated a target ship anchored in the channel. Ordnance officers and awestruck spectators could only wonder at the destructive capacity of the Rodman gun, causing Rodman to design new devices to more accurately measure projectile velocities (an unprecedented 1735 fps) as well as the internal and external forces exerted by his weapons. Though the 20-inch gun was never deployed against an enemy and the government only authorized the casting of two of the giant guns, their deterrent effect was great. The Rodman guns became a symbol of America’s—and Pittsburgh’s—industrial might.

More than a decade after the Civil War, the 20-inch Rodman gun was still considered a super weapon and an unequaled example of American power. In 1876, the nation celebrated its centennial with a year-long exposition in Philadelphia. One of every type of Rodman gun, from mortars to Columbiads, would be exhibited—including one of the 20-inch guns. The problem was getting the monster gun to Philadelphia. The 100-ton ship nearly capsized when the steam crane operator failed to center the big gun on the deck. By the time the ship reached Philadelphia, alarmed exposition officials and reporters noted that the load sank the vessel to within a foot of its gunnels. When steam cranes, working at the limit of their capability, raised the gun, no cribbing blocks were needed by the riggers aboard the ship, which rose with the gun, to the amazement of all.

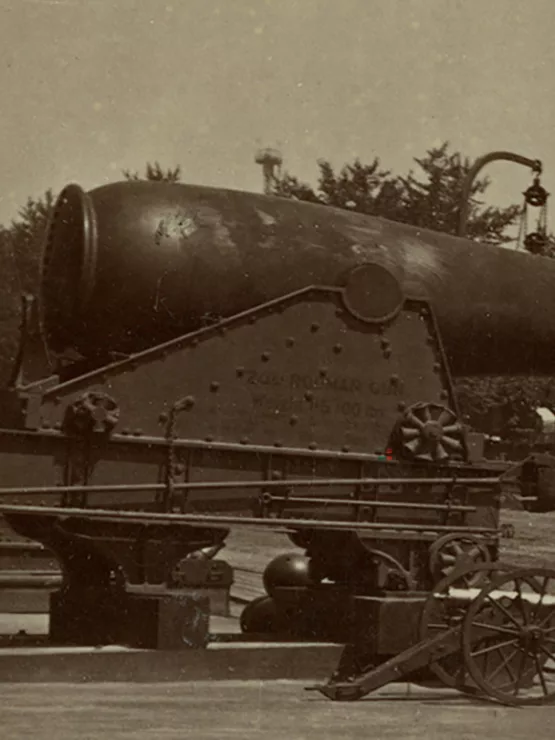

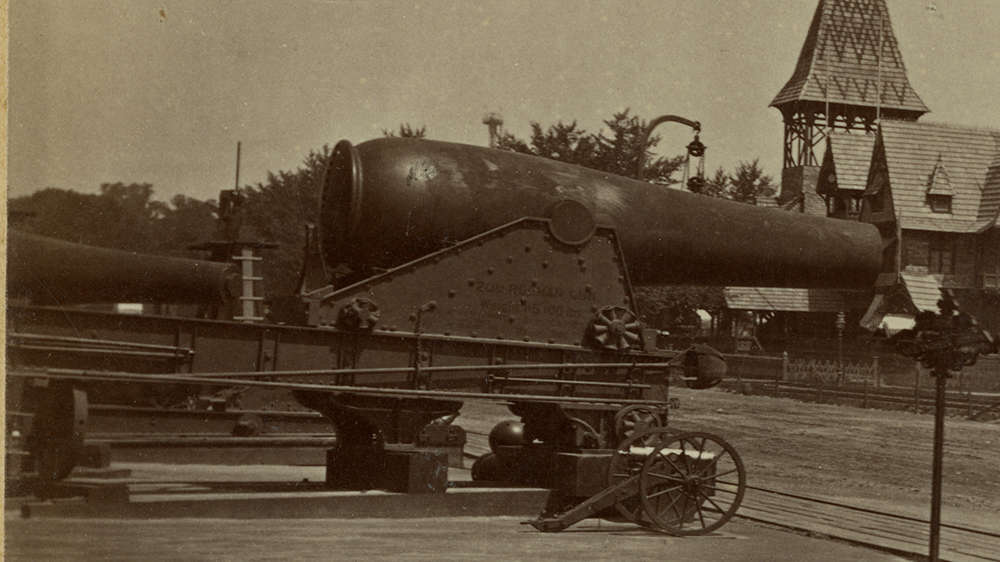

Rodman’s big gun was the hit of the Centennial Exposition. Millions gaped at the huge weapon which the Army whimsically chose to exhibit next to a model 1841, 12-pounder mountain howitzer—the smallest cannon in the U.S. service—weighing in at just 500 pounds (barrel and carriage). Alongside the big gun were the 20-foot long rammers and the hook-shaped winch the crew needed to hoist the ball and load the gun—a procedure that could be accomplished in under two minutes. Also on display were a variety of 20-inch rounds: explosive shells (each capable of holding a 25-pound bursting charge), solid shot (weighing 1,080 pounds each), and “cored shot” (with small hollow cavity to reduce weight and thereby extend the gun’s range. No one who saw the exhibit doubted that the muzzle-loading cannon had reached its zenith and that only American ingenuity and industry were capable of such an achievement.

A full-size replica of Rodman’s 20-inch gun may be seen today at the Heinz History Center. Beside the big gun is a tiny 12-pounder mountain howitzer. Look closely at the muzzles of the two cannons and you will see the initials “TJR”—for Thomas Jackson Rodman.

Learn more about Thomas Rodman and see one of the oldest photographs from the Detre Library & Archives’ collections on this blog post: Could this be the oldest photograph of a Pittsburgher? … Maybe.

Andy Masich is the president and CEO at the Senator John Heinz History Center.