William “Bill” Snyder (c. 1897-1984) was a bootlegger and gambler whose brief career in the 1920s and 1930s forever changed Pittsburgh. Along with Gus Greenlee, Woogie Harris, and Richard Gauffney, Snyder introduced numbers gambling to the city and became one of its earliest top bankers and racket leaders. For a brief time, Snyder enjoyed the middle-class wealth and status that being a gambling entrepreneur brought him. One symbol of that wealth was a modest Hill District bungalow he bought in 1928.

I went to photograph the bungalow earlier this year for a research project on the history of numbers gambling in Pittsburgh. The house is an unassuming yet significant part of Pittsburgh’s social and economic history. There’s nothing on its exterior that speaks to the building’s association with the rise of a Black middle class in Pittsburgh or the criminal activities that took place there.

As I was taking pictures in the street across from the house, the owner arrived and we began speaking. Upon hearing about the home’s former owner and the reason for my visit, she told me about an unusual object that she and her husband found in the basement after they bought the property in 2005: a very large safe.

A little history of numbers gambling is essential to understanding the safe’s significance.

Numbers is a daily game like a lottery. People bet small amounts of money – a nickel, a dime, or quarter – that they would guess each day’s three-digit number derived from stock market returns reported in newspapers. Introduced by African Americans in Harlem during the first decade of the 20th century, numbers gambling rapidly spread to cities and rural communities throughout the nation. Pullman porters, musicians, baseball players, and itinerant laborers brought the game to Black neighborhoods like the Hill District.[1]

Some oral histories credit Richard Gauffney, a Washington, D.C., native who worked in construction, as the person who likely introduced numbers to Pittsburgh.[2] Within a few years, Gauffney, Greenlee, Harris, and Snyder had built a bustling local economy that employed hundreds of runners (salespeople) and writers (managers) in the 1920s. The bankers took in the money and paid out the winnings. The odds of winning were one in a thousand and the payouts were substantial: 600 to one. A nickel bet could yield a $30 windfall.[3]

By the late 1920s, Greenlee and Harris had become wealthy enough to leave the Hill District tenements where they lived. The pair bought neighboring, fashionable Frankstown Road bungalows in Pittsburgh’s East End.[4] Snyder bought his upper Hill District home from the family of one of Pittsburgh’s first African American police detectives.

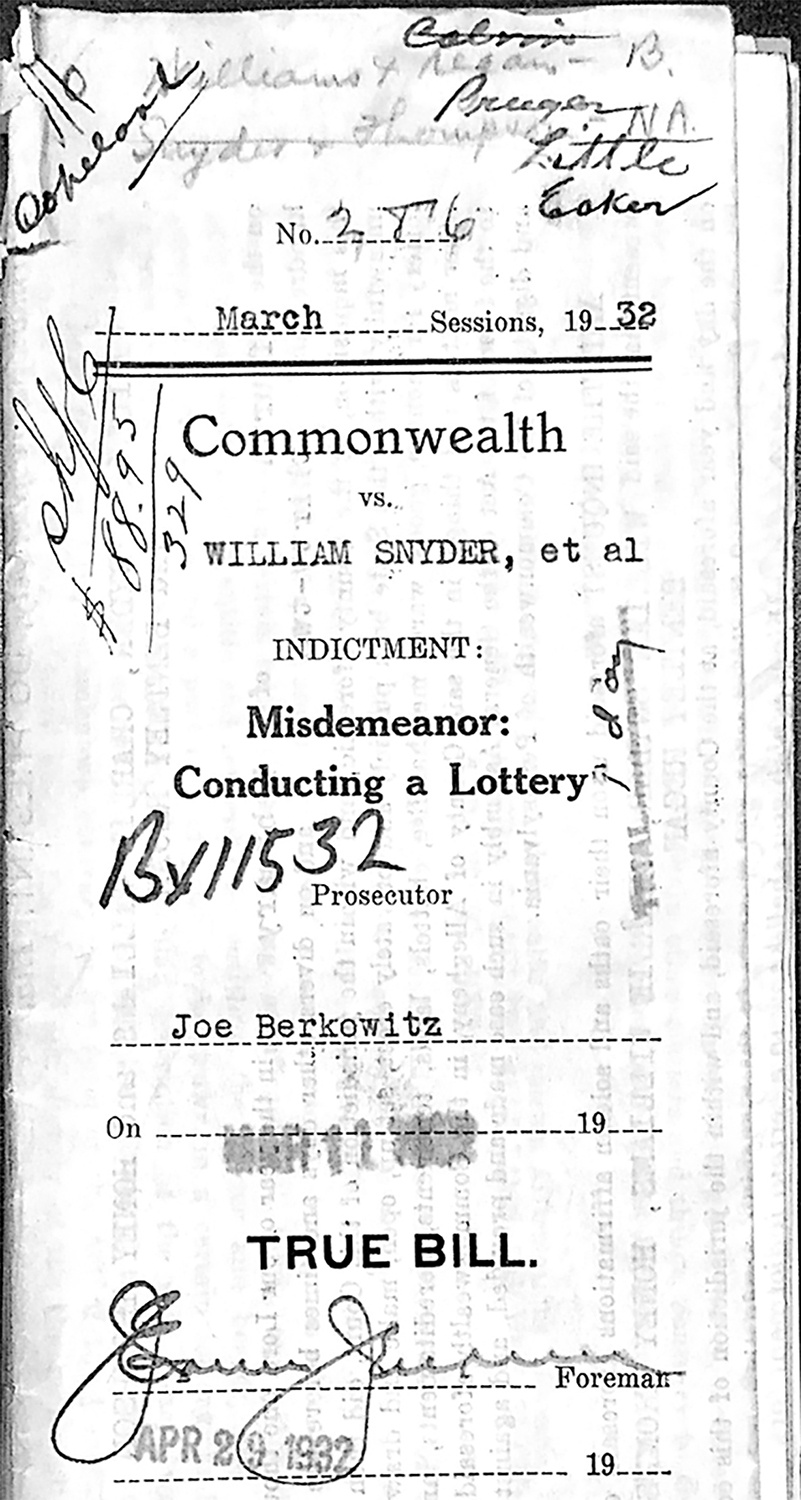

Snyder only lived in the home for eight years. In that time, he racked up arrests for running his Hill District numbers operation out of Wylie Avenue storefronts and tenements. At the end of the day, Snyder collected his take and returned home with the cash.

One day in 1930, Snyder returned home with his money when he was “taken for a ride” and robbed. He told police and reporters that he was a plasterer. The $3,000 that was stolen, two cars, and nice home came from his job as a plasterer, he told police and newspaper reporters as he denied involvement in the numbers racket. “I’m a plasterer and a good one, too,” Snyder exclaimed.

Numbers bankers like Snyder were among the wealthiest people in America’s Black communities. Under Jim Crow, redlining, and other discriminatory business practices, they not only provided economic opportunities through gambling, but they also invested heavily in their neighborhoods through philanthropy and what we today call “community development.”

The women and men who became numbers bankers converted their gambling capital into social capital as a way to keep Black wealth in Black neighborhoods. They donated heavily to churches and provided loans to Black businesses. Spreading the wealth built up goodwill and a solid customer base but it also helped to uplift the race.[5]

Greenlee and Harris built enduring legacies in Pittsburgh through their goodwill and the legitimate businesses their gambling enterprises capitalized.

The numbers bankers’ homes frequently served as their back offices and vaults. Famed photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris described safes hidden in his brother Woogie’s home similar to the one hidden in Snyder’s former home. “My brother, he had 2 safes in the cellar,” Harris told University of Pittsburgh historian Rob Ruck in 1981. “He kept a lot of his money in there.”[6]

Snyder never achieved the prominence of his peers. The wealth didn’t last – the bungalow was foreclosed in 1936 – and he slipped back into a life of petty crime. He died in 1984 at age 87.

Author’s Note: To protect the privacy of the current homeowner, the exact location and her name are not used in this blog post.

[1] Ruck, Robert. Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh. Illini Books ed. Sport and Society. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993; White, Shane, Stephen Garton, Stephen Robertson, and Graham White. Playing the Numbers: Gambling in Harlem between the Wars. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2010.

[2] Hill, Ralph Lemuel. “View of the Hill: A Study of Experiences and Attitudes: The Hill District of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, from 1900 to 1973.” Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, 1974; Black Sport in Pittsburgh Oral History Collection, University of Pittsburgh Libraries, Archives and Special Collections.

[3] Hayllar, Ben. “All About the Numbers.” Pittsburgh Renaissance, 1972; Ruck, Sandlot Seasons.

[4] Finley, Cheryl, Teenie Harris, Laurence Glasco, and Joe William Trotter. Teenie Harris, Photographer: Image, Memory, History. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press : published in cooperation with Carnegie Museum of Art, 2011. https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/teenie-harris-book.pdf.

[5] Harris, LaShawn. “Playing the Numbers: Madame Stephanie St. Clair and African American Policy Culture in Harlem.” Black Women, Gender + Families 2, no. 2 (2008): 53–76; Playing the Numbers.

[6] Rob Ruck interview with Teenie Harris, February 23, 1981, Black Sport in Pittsburgh Oral History Collection.

David S. Rotenstein is a Pittsburgh public historian and folklorist. He has written on Pittsburgh’s livestock and leather industries and he is researching the history of numbers gambling in Pittsburgh. Dr. Rotenstein teaches in Goucher College’s graduate historic preservation program.