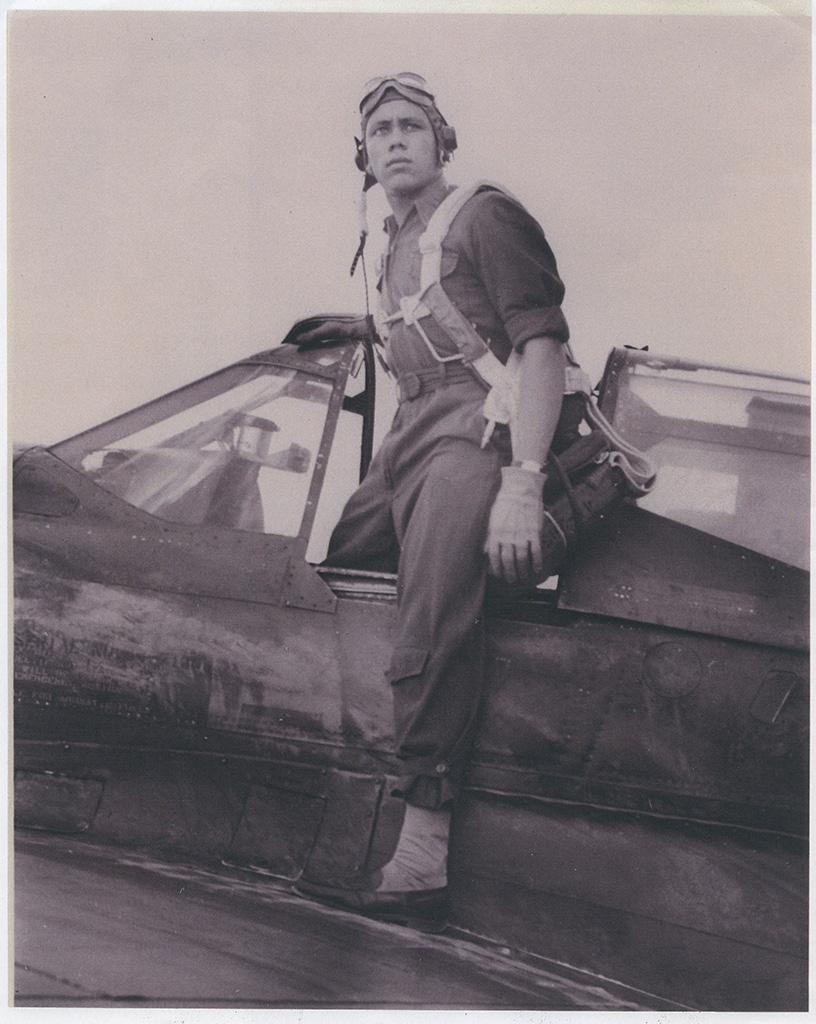

The 332nd Fighter Group, known as the Tuskegee Airmen, became the first African American pilots in the U.S. military. More than 80 of them called Western Pennsylvania home. During World War II, the Tuskegee Airmen formed the 332nd expenditionary force and the 447th bombardment group.

In 1940, the U.S. military was segregated and African Americans were prohibited from serving as pilots. Prejudgment began to bend to pressure from civil rights groups and the African American press, including The Pittsburgh Courier, resulting in the Tuskegee experiment.

Six historically black colleges participated in the pilot training program, formed in 1938 and originally called the Civilian Aviation Corps or Civilian Pilot Training Program. The group’s name was derived from the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, which graduated its first class of pilots in 1942.

Over 1,000 men trained as pilots, navigators, bombardiers, mechanics, support staff, and instructors for the Tuskegee Army Air Corps between 1941 and 1946. Of those, approximately 445 were deployed overseas to engage in combat missions over North Africa, Italy, and German-held territory.

Tuskegee pilots faced segregation and discrimination, but the squadron came to be respected by many of their white counterparts for their bravery and skill. They completed more than 1,500 missions and earned numerous honors, including approximately 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses, 14 Bronze Stars, 744 Air Medals, and 8 Purple Hearts.

I

n 1995, an HBO movie entitled, “The Tuskegee Airmen,” honored these heroes and 12 years later, President George W. Bush presented the Airmen with the Congressional Gold Medal.

Of the Tuskegee Airmen from Western Pennsylvania, 13 hailed from Homewood, 11 from the Hill District, seven from Sewickley, six from Beltzhoover, and three from the North Side. You can visit the Tuskegee Airmen monument in Sewickley Cemetary, organized by Western Pennsylvania researcher Regis Bobonis.

Visitors to the Heinz History Center can learn more about the legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen as part of the long-term exhibition, Pittsburgh: A Tradition of Innovation.

This post was originally written by Breanna Smith, former communications assistant at the Heinz History Center.