A woman sits on the edge of a box frame holding a rifle as she stares into a bin filled with guns. Who is she? What is she doing with so many weapons?

The image is from the Pittsburgh Public Schools Collection, but its meaning is a mystery. Whoever assembled the weapons, odds are that they didn’t leave records explaining their purpose. People who hide stores of guns rarely do. (In fact, if you know anything about this image, we’d love to know.)

Some subjects continue to fascinate us but present a challenge for museums. Crime is an unwelcome but integral part of any city’s history. It affects relationships between people and neighborhoods. It focuses debate on enforcement and prevention. Crime can illuminate the benefits of new technology but also raise darker questions about its impact. What kinds of objects help museums explore a topic that may lead in uncomfortable directions?

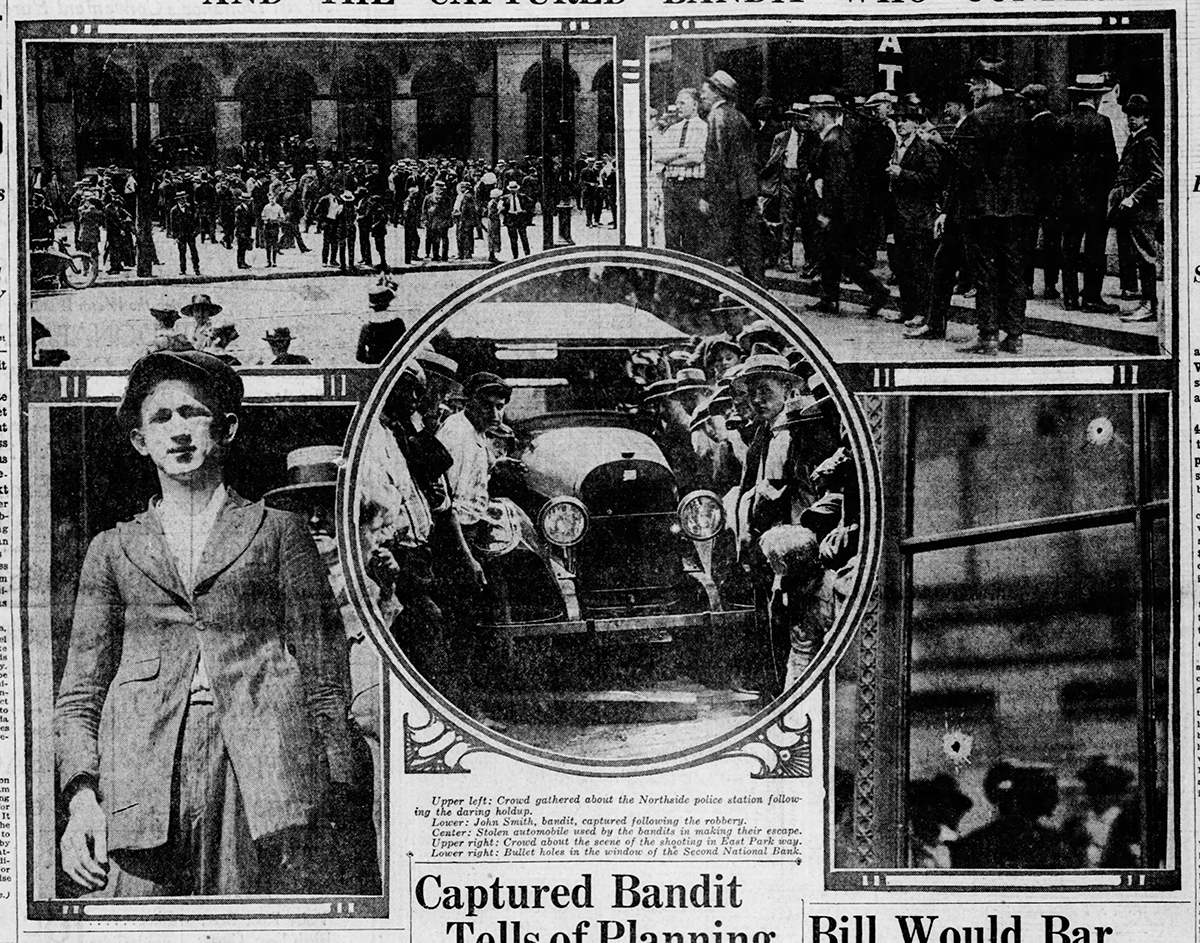

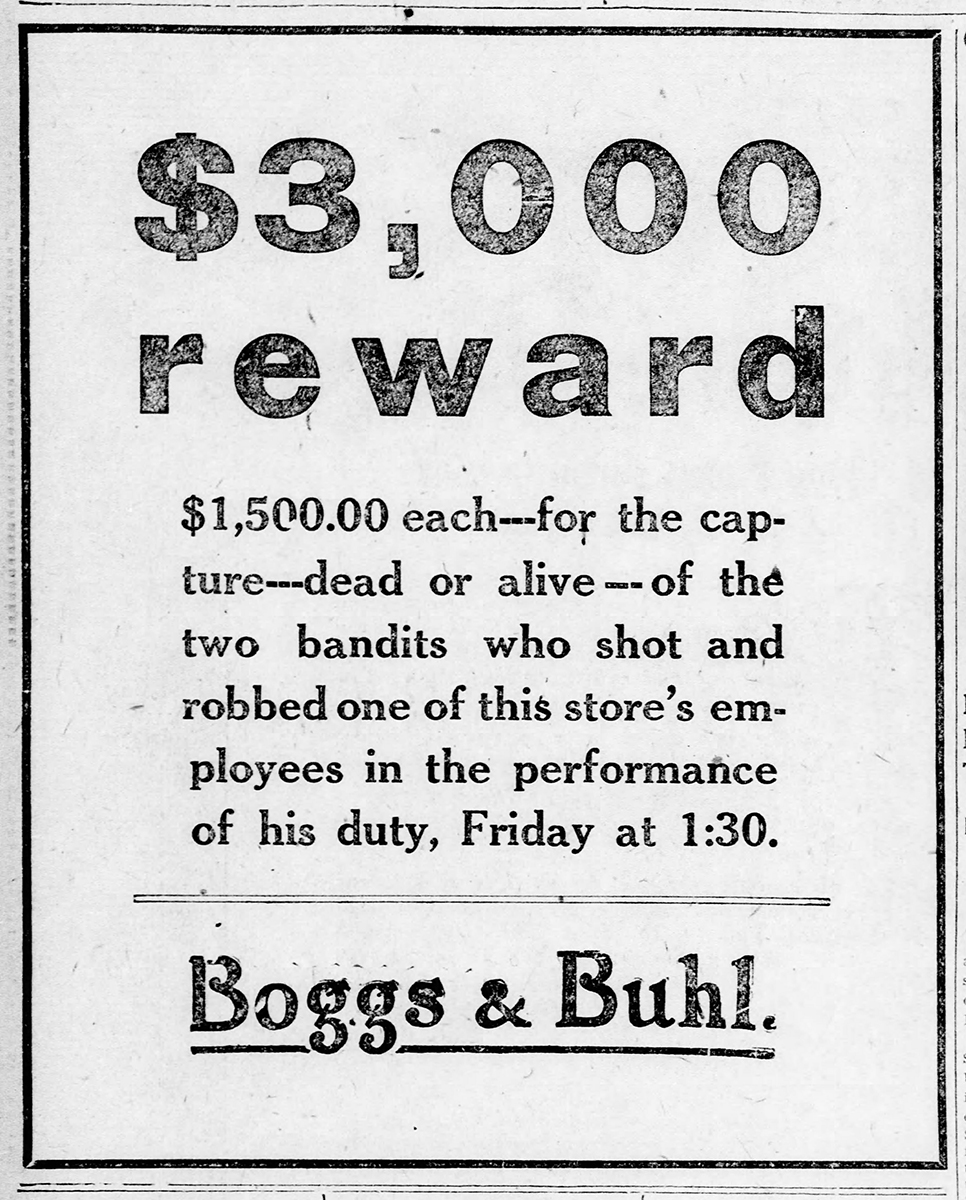

A simple gray felt hat in the History Center collection is one example. The hat appears unremarkable until close examination reveals multiple bullet holes. It belonged to off-duty police officer Charles H. Schultz, who, 95 years ago on June 10, 1921, was on Federal St. on the Northside when three armed bandits jumped out of a car and robbed two men making a bank deposit for Boggs & Buhl Department Store. One employee was shot, and the assailants fired wildly into the crowded street. Officer Schultz confronted the bandits as they fled. Shots were exchanged as Schultz grabbed one of the men and wrestled him to the ground. When Schultz arrived at the Northside police station, the evidence of his struggle was obvious. He stood before the desk sergeant, took off his hat, and, according to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “showed four holes through the crown, made by steel bullets.”

The Boggs & Buhl robbery occurred in broad daylight at 1:30 p.m. Evidence and suspects were rounded up from Aspinwall to Swissvale. One newspaper called the crime “unparalleled” in the city’s history. In fact, crime across the nation had become all too common. As early as January 1921, a former superintendent of the Pittsburgh Police urged the creation of a national detective agency to fight the growing outbreak. Even children noticed. Just two days after the Boggs & Buhl robbery, a girl in Lawrenceville was accidentally shot by her brother while the children played “holdup.” Fortunately, she survived.

Many people blamed the lawlessness on prohibition; others blamed economic inequity and increasingly easy access to automobiles. A frightened public demanded action.

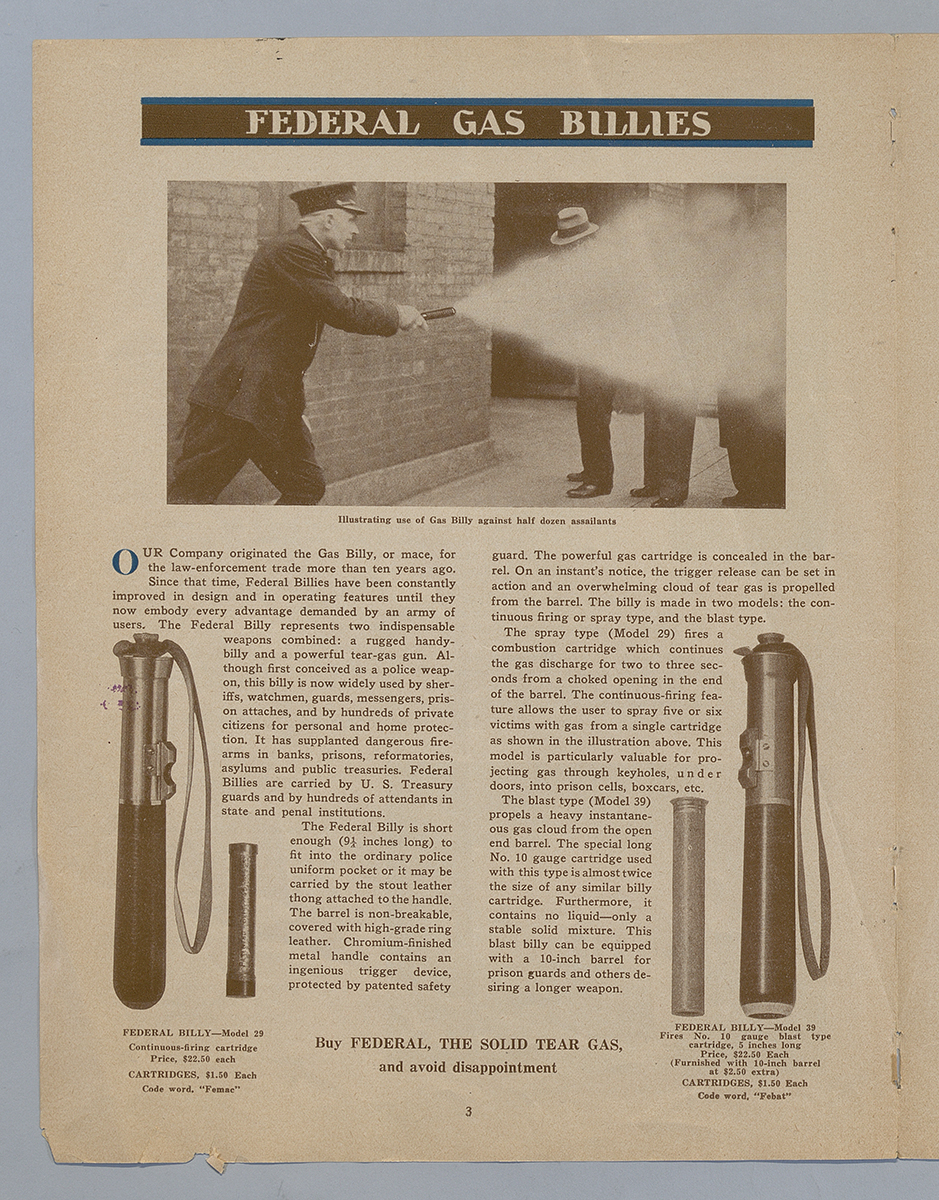

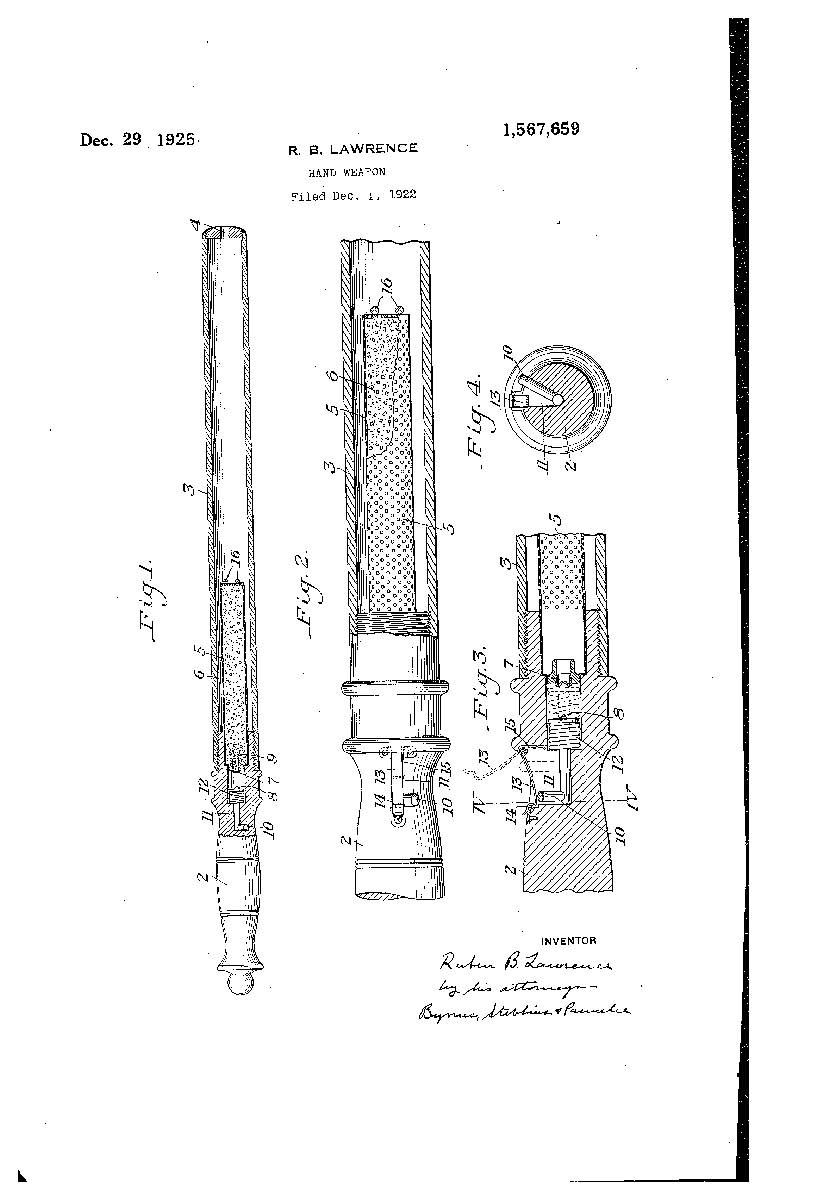

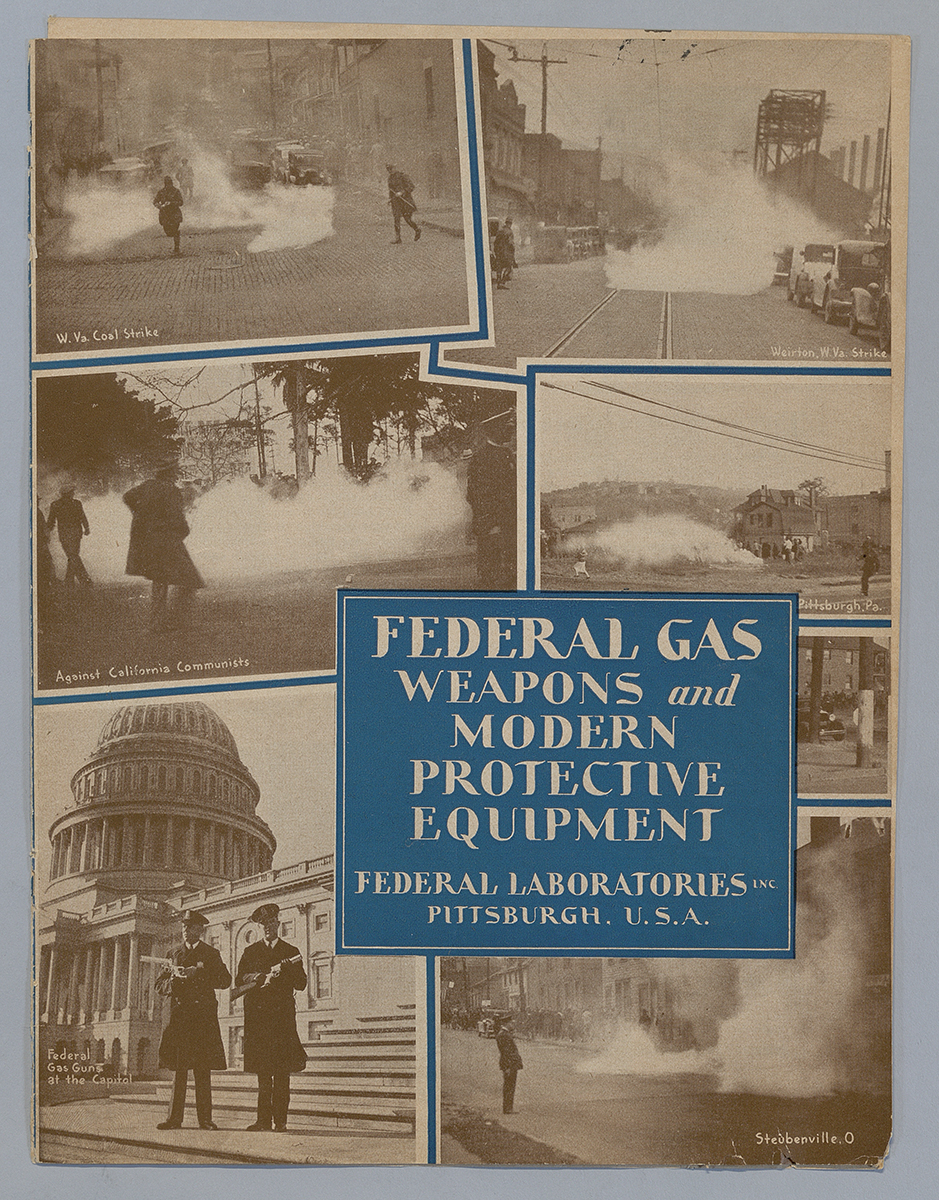

One response is found in another set of History Center artifacts. Called “Federal Gas Billies,” these billy clubs fired a spray or canister of America’s newest crime prevention tool: tear gas. Emerging out of World War I, tear gas was regarded as a “humane” weapon that incapacitated but did not kill. Between 1922 and the 1930s, a Pittsburgh-based company, Federal Laboratories, Inc., became one of the nation’s leading producers of tear gas products. They developed and patented multiple delivery devices, including a robbery prevention system disguised as lightbulbs. Once installed in a bank vault, the “bulbs” flooded the space with tear gas if they were triggered by a break-in.

Today, tear gas used in urban settings carries a host of complex meanings. In fact, Federal Laboratories ran into legal problems by the late 1930s when people began to question how and to whom they sold their products. But as artifacts, the Federal Gas Billies vividly illustrate how technology drawn from one field (military warfare) can migrate to another when prompted by societal pressure. They remind us that crime can shape local business as much as other factors. That the use of such items would be debated into the next century only adds to their value as part of the museum’s collection.

So, what do you think? What objects today could help document Pittsburgh’s hidden crime history? What part of that story would you choose to tell?

Leslie Przybylek is curator of history at the Heinz History Center.