Pittsburgh has had a Greyhound station at its current site so long (more then 60 years) that few people remember the previous bus station across the street, at the site of today’s Federal Building. That station was not as dazzlingly deco as other Greyhound terminals of the 1930s but nonetheless brought an air of luxury and sophistication to local transportation. Bus travel then was seen as exciting and glamorous, like train and air travel; cars could not offer reclining seats or air conditioning, or release from having to do the driving.[1] Bus travel also had a huge advantage by serving thousands more places that trains and planes could not reach.

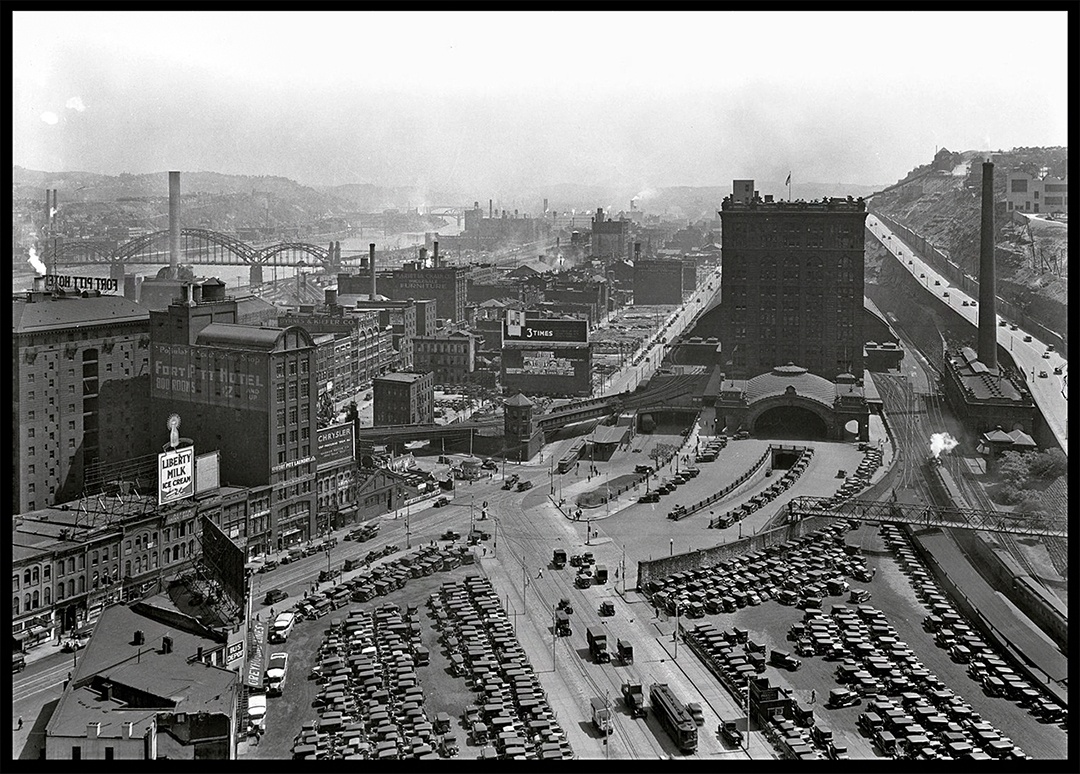

Pittsburgh, like most cities, had a hodgepodge of bus depots in the 1920s and early ’30s, small and crammed into places like drug stores and pool halls, with buses idling on the streets around the clock. Greyhound served its customers from a storefront at 969 Liberty Ave., but when the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) acquired a 50 percent interest in Greyhound Lines in 1929, the company took over the Lafayette Hotel at 1010 Liberty Ave., across from the railroad’s passenger station. The old hotel was remodeled to include cutting edge amenities like a spacious waiting room, lady’s parlor, telegraph office, barber shop, and restaurant. Greyhound ordered 17 new buses for its Pittsburgh-Philadelphia route[2] and built a new garage on the North Side too. Grant Street’s recent makeover (see Grant Street post) left a sprawling dirt lot adjacent that was perfect for loading and unloading buses.

In the early 1930s, Greyhound began applying streamline design to its buses and buildings, outpacing the railroads, which were burdened with dark, Victorian stations. The company employed some local architects, but for much of its work east of the Mississippi, it turned to Thomas W. Lamb & Associates of New York, known for designing exotic movie palaces in the 1910s. A step ahead of competitors, Greyhound standardized its terminals, buses, and even its uniforms into a coordinated and stylish package.[3]

By the mid-’30s, Greyhound had become the world’s largest motor coach company, with 2,500 buses, 200 garages, and 12,000 employees helping to cover 50,000 route-miles daily.[4] The Pennsylvania Greyhound Lines division led the chain in miles and passengers carried, with Pittsburgh as the meeting point on its main transcontinental route. The city needed a station to match its importance; Greyhound’s hotel-turned-depot and its adjacent parking lot were a perfect location.[5]

In May 1936, the depot moved from the hotel to temporary quarters in PRR offices across from the Fort Pitt Hotel (now site of a Jimmy John’s storefront in the David L. Lawrence Convention Center).[6] Work on the new station started that September and was expected to take a year and a half, but the building was move-in-ready after six months at a total cost of $300,000.

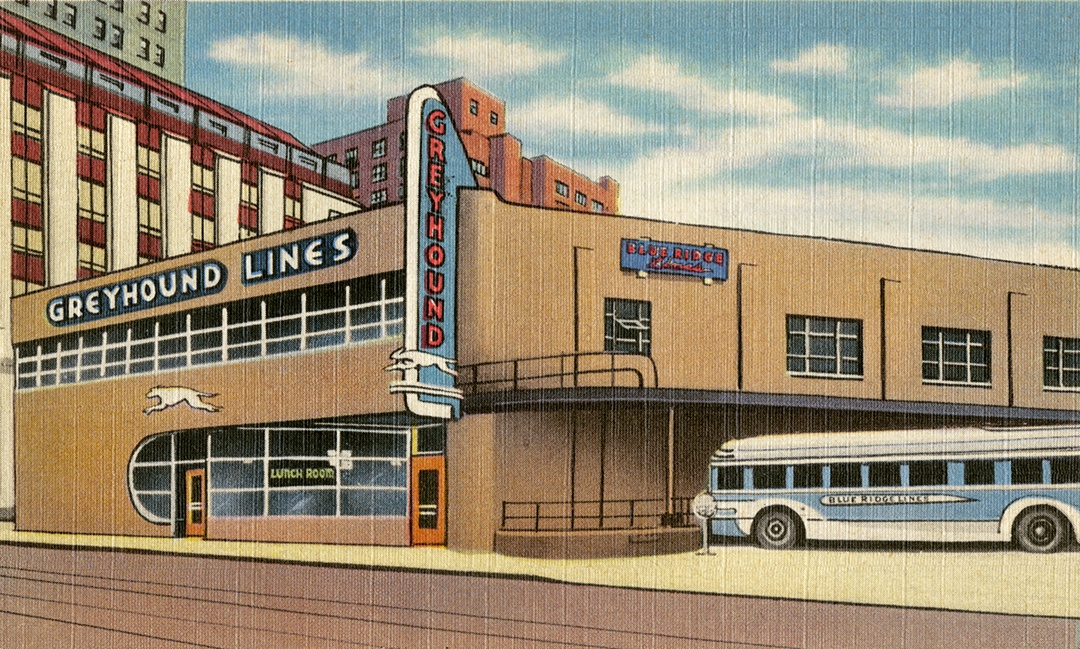

When the bus terminal opened on March 13, 1937,[7] ads declared, “this new travel center is as modern as the streamlined Greyhound Cruisers themselves.”[8] Those ads do made it look like a streamlined deco masterpiece, though in reality the exterior was businesslike; there were streamline touches but not done in an overall ornamental package.

The building was made of reinforced concrete on structural steel, two floors and a basement, 182 feet deep and 53 feet wide at its center. Two entrances were covered in blue-face brick, with blue-cast stone for the coping. The sides were stuccoed above the canopy, with Kittanning brick below. Interior walls were canary yellow, cinnamon brown, and tan, with a ceiling of bluish gray. Woodwork was made of black walnut. Except for the restaurant’s tile, the rest of the floors were all terrazzo.[9]

The Liberty Avenue side rose three stories, but only two levels faced Grant Street. Instead, the Liberty entrance opened into the basement, which had a lobby, barber shop, tailor shop, two stores, storage room, parking office, drivers’ room, and porters’ room. Stairs ascended to the main waiting room where customers found six ticket windows, information desk, baggage and parcel check, travel bureau, dispatcher’s office, and restaurant. The mezzanine held offices, restrooms with showers, and private dressing rooms for the public.[10]

Buses entered and departed from Grant Street using a ramp that circled the building, with nine sawtooth slots for loading and unloading. Despite Greyhound hoping to be the sole operator, 15 other companies used the terminal too, from Penn-Niagara to Somerset Bus Line.[11] Blue Ridge Bus Lines alone ran more than 100 buses from it daily, with routes from Ohio to Washington, D.C., plus suburban service to towns like Avella and Verona.[2] The station was hopping with 320 buses arriving and departing daily, an average of one every 4-1/2 minutes (obviously higher during daylight hours).[13]

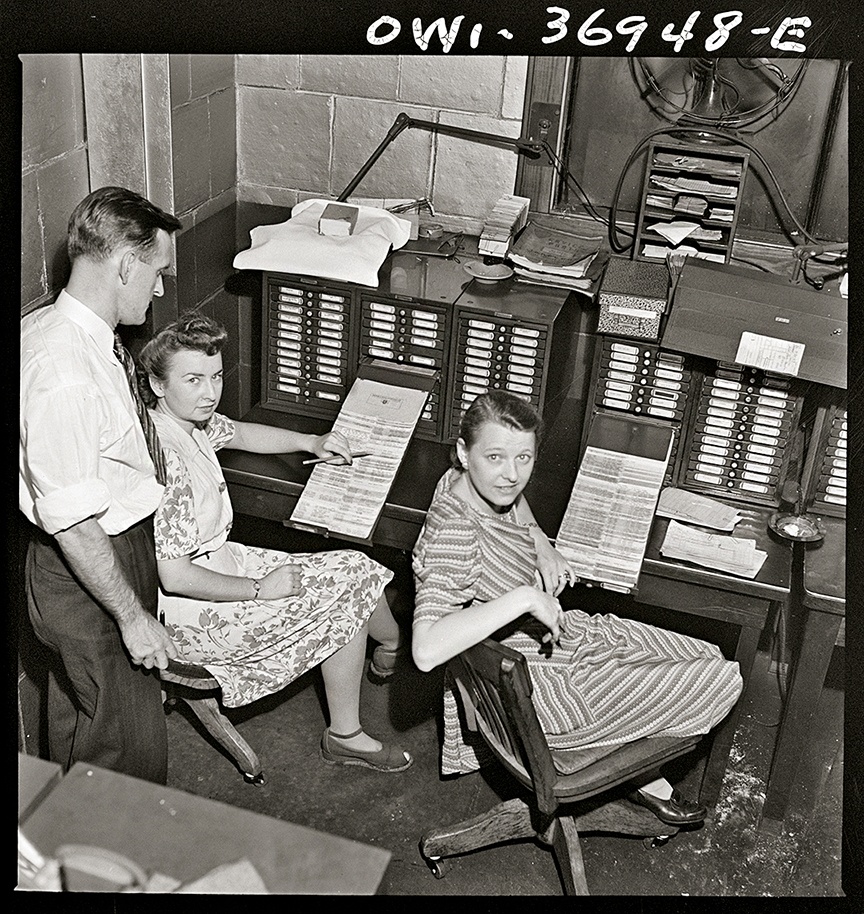

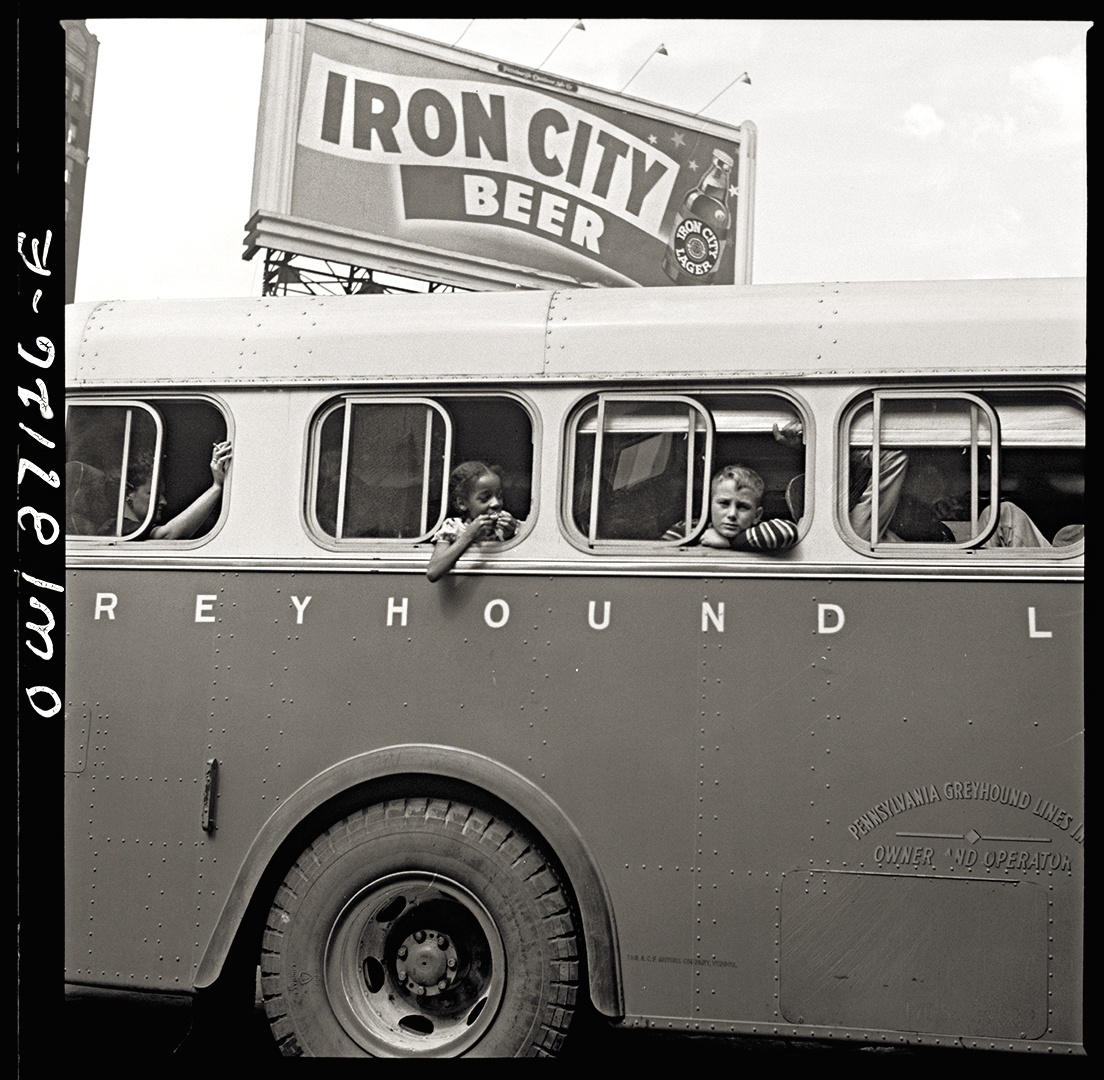

We know all this, and can picture it, because of 22-year-old Esther Bubley, who took a bus trip in September 1943 for the Office of War Information to photograph New Deal programs. It was the golden age of photojournalism, when daily newspapers still ran grainy photos and television had yet to take hold. Magazines like “Time” and “Life” brought clear, crisp images into American households. Luckily, Bubley took lots of photographs at Pittsburgh’s Greyhound station—drivers, workers, and passengers, with the terminal prominent in most views too. If not for her photos, almost no images of the station would exist.

Twenty years later, demand for photojournalists was in decline as consumers turned to television for their news and entertainment.[14] Pittsburgh’s Greyhound terminal had lost its luster too; in 1959, a new station was built on 11th Street facing the old station; the aging deco depot was demolished and a new Federal Building opened on the site in 1964.[15] The new $4 million Greyhound station could serve 21 buses simultaneously and had a parking garage attached.[16] Still, dreams for an even-better station brought its demise too, when it was replaced in 2008 by a similar-looking building and parking garage. It was to be a multi-modal transportation nexus that would “brighten a dismal corner of downtown with a stylish building”[17] but a decade later, it leans towards shabby with nary an air of luxury or sophistication.

Look for the story of how Grant Street became home to Greyhound in our other post, When Grant Street Got a Zigzag.

[1] Jeffrey L. Meikle, Postcard America: Curt Teich and the Imaging of a Nation, 1931-1950 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016), 266-267.

[2] “Bus Systems Control Gained by Railroad,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 15, 1929, p. 1; “P.R.R. Confirms Bus Line Deal,” Pittsburgh Press, June 7, 1929, p. 1.

[3] Foreword by Richard Longstreth in Frank E. Wrenick, The Streamline Era Greyhound Terminals: The Architecture of W.S. Arrasmith (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2007), p. 2.

[4] “Greyhound’s Rise Called American Industrial Saga,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 13, 1937, p. 10.

[5] “Bus Riding Popular,” Pittsburgh Press, June 17, 1928, p. 21.

[6] “Buses Maintain Service, Claimed,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 21, 1936, p. 15. Part of Columbus Avenue was renamed California c. 1935.

[7] “Open Greyhound Terminal Tomorrow,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 12, 1937, p.13.

[8] “Of Course” ad, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 15, 1937, p. 6.

[9] Manferd Burleigh and Charles M. Adams, eds., Modern Bus Terminals and Post Houses (Ypsilanti, Mich.: University Lithoprinters, 1941), p. 91, original from University of Michigan, online at hathitrust.org. For many more blueprints and descriptions, see American Locker Company, Railroad and Bus Terminal and Station Layout (Boston; American Locker Company, 1945), online.

[15] “Public is Given Chance to View Travel Facility,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 13, 1937, p. 10.

[11] “Bus Terminal Open Saturday,” Pittsburgh Press, March 11, 1937, p. 22. “Greyhound Opens $300,000 Bus Terminal Today,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 13, 1936, p. 10.

[12] Ad, Blue Ridge Lines, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 13, 1937, p. 11.

[13] “Greyhound Opens $300,000 Bus Terminal Today,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 13, 1936, p. 10.

[14] Bonnie Yochelson, Biography of Esther Bubley at www.estherbubley.com/bio_frame_set.htm; Esther Bubley’s photos are among the more than 107,000 prints in the Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Photograph Collection at the Library of Congress, available at www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/fsa/.

[15] Today it is the William S. Moorhead Federal Building to honor Rep. Moorhead, who served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1958–1981, per “Moorhead Federal Building Dedication Tuesday,” Pittsburgh Press, May 10, 1981, p. B-13, and “Federal Building Renamed,” Pittsburgh Press, May 12, 1981, p. 6.

[16] Wrenick, p. 169, and “Greyhound’s New Look,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, June 25, 1959, p. 29.

[17] Greyhound, City Plan New Terminal,” Tribune-Review, February 22, 2003.

Brian’s full story of Grant Street and Greyhound can be found in the Spring 2019 Western Pennsylvania History magazine, available from the History Center’s Museum Shop and for purchase online.

Also look for Brian’s feature on Esther Bubley’s bus trip in the Spring 2019 issue of Pennsylvania Heritage magazine, available from the Pennsylvania Museum and Historical Commission here.

Brian Butko is Director of Publications at the Heinz History Center, and author of books on diners, Isaly’s, Roadside Attractions, and Kennywood.