This post has been adapted from an article featured in the Spring 2018 issue of Western Pennsylvania History.

The Keystone State is known for having some of the strictest alcohol laws in the U.S. If Pennsylvanians want to purchase wine or liquor, they must do so at a state-run store. Beer must be purchased at a distributor, a bar, or a brewery. Some grocery stores and gas stations are licensed to sell beer and wine from specific sections of the store. Where did Pennsylvania’s liquor laws come from, and why are they so strict compared to other states? A look at the gubernatorial administrations of Gifford Pinchot provides some answers.

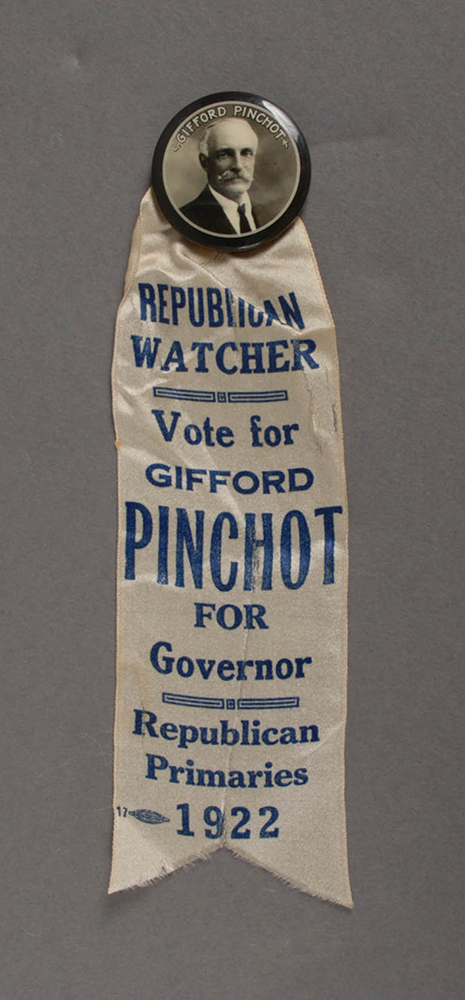

By the time he ran for office in Pennsylvania, Gifford Pinchot (1865-1946) had a successful career in the conservation movement, serving as the first Chief Forester of the U.S. Forestry Service formed under President Theodore Roosevelt. In this position, Pinchot worked at the federal level to preserve forests from destructive lumbering practices in the late 19th century, in a way that also benefited the members of society. This philosophy eventually transcended forestry and influenced his political career.[1] When he ran for governor in 1922, his Progressive Republican platform attracted union members, industrial workers, farmers, and newly minted women voters. This support, combined with a split in the state Republican Party leadership, paved the way for both of Pinchot’s surprising victories (he served from 1923-1927 and again from 1931-1935). His “dry” stance, or support of Prohibition, also contributed to his election.[2]

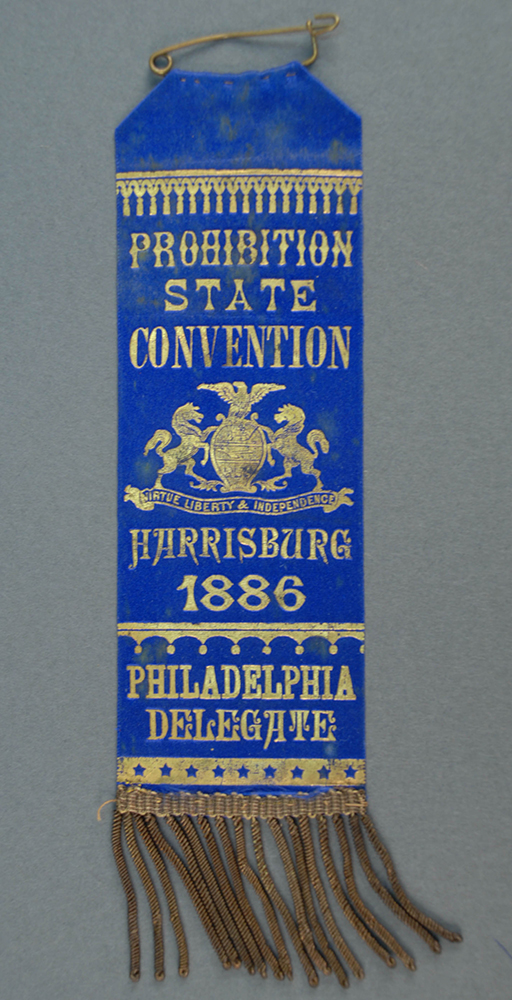

Prohibition, implemented by the 18th Amendment to the Constitution in 1920, made the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” illegal.[3] Pinchot formed his unfavorable opinion of alcohol and its effects after witnessing drunken behavior as a young man in college and while studying forestry in Europe, an opinion he was not alone in.[4] By 1923, Prohibition enforcement in Pennsylvania was not going well. Pinchot’s predecessor, Gov. William Sproul, admitted as his term ended that Prohibition laws were not working, and that bootlegging had spiraled out of control. “We are raising a fine brood of criminals which it will require stern measures to suppress,” Sproul lamented.[5] Pinchot rose to the challenge; he believed that “proper enforcement of Prohibition will add uncountable millions to the wealth of the United States; will enormously increase the prosperity of our people and will raise happiness and welfare, especially of our women and children, to a new and higher plane.”[6] Shortly after his inauguration, Pinchot immediately began cracking down on lawbreakers. [7]

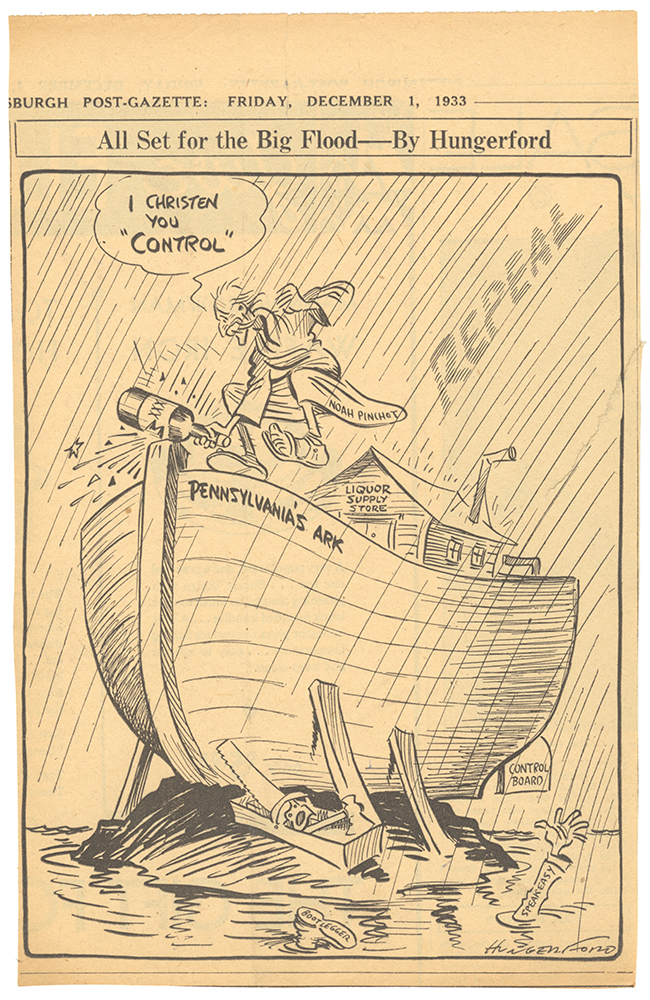

Ultimately, Prohibition fell far short of Pinchot’s lofty goals. Nationally, criminal activity had increased, and enforcement of the law decreased, and the Great Depression had caused a tax revenue shortage that a tax on alcohol could help recover. In 1933, the 21st Amendment passed, repealing Prohibition 13 years after its implementation.[8]

When Prohibition was repealed two years into his second term, Gov. Pinchot worked with a special legislative session to maintain strict regulations on alcohol.

This plan created a monopoly on liquor sales, run by the State Liquor Control Board and facilitated through the state store system that Pennsylvanians are familiar with today. The Liquor Control Board licensed and defined the institutions that served alcohol, set serving and state store hours, and regulated prices. Pinchot believed the competition between private retailers would play into the hands of corrupt politicians and distillers, and low prices would discourage bootlegging.[9] Tax revenue from the state system partially funded state social programs for the unemployed, care for the elderly, and schools—welcome relief during the Great Depression, when unemployment in Pennsylvania reached a staggering 40 percent by 1935.[10]

The legacy of Prohibition in Pennsylvania is still experienced today. Eighty years later, the actions that Gifford Pinchot and the state government took at Prohibition’s death knell are felt by Pennsylvanians every time they stop by the liquor store or beer distributor. We also see this legacy on the local level; municipalities choose their stance on alcohol, and as of August 2017, there were 686 throughout Pennsylvania that remained “dry.”[11] While changes have recently been made to state liquor laws, liquor control continues to be an issue that Pennsylvanians grapple with at the polls.[12]

[1] Char Miller, “Introduction,” in Gifford Pinchot: Selected Writings, ed. Char Miller (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017), 2,6.

[2] James A. Kehl and Samuel J. Astorino, “A Bull Moose Responds to the New Deal: Pennsylvania’s Gifford Pinchot”, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 88, No. 1 (Jan.,1964), pp. 37-51; Miller, Char, Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism, pp 250-258.

[3] Amendment XVIII, The Constitution: Amendments 11-27, National Archives, accessed November 27, 2017.

[4] Char Miller, Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism (Washington: Island Press, 2001), 251.

[5] United Press, “State Very Wet, Sproul Admits to Legislators” The Pittsburgh Press, January 2, 1923, 2.

[6] Gifford Pinchot, “Why I Believe in Enforcing the Prohibition Laws,” in Gifford Pinchot: Selected Writings, 145.

[7] Dale Van Every, “Federal Agents May Aid Pinchot Dry Plan”, The Pittsburgh Press, January 28, 1923, 1,8.

[8] Daniel Okrent, “Wayne B. Wheeler: The Man Who Turned Off the Taps”, Smithsonian Magazine (May 2010), accessed 11/27/2017.

[9] Gifford Pinchot, “Liquor Control in the United States: The State Store Plan”, in Gifford Pinchot, Selected Writings, 173, 175.

[10] “Governor Gifford Pinchot”, Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission, accessed December 4, 2017.

[11] “Wet Versus Dry Municipalities”, Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board; “Listing of Dry/Partially Dry Municipalities”, Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board.

[12] Scott Bomboy, “Pennsylvania to fight one of Prohibition’s last battles”, Constitution Daily Blog, National Constitution Center, January 30, 2013, accessed December 1, 2017.

Carrie Hadley is a collections associate at the Heinz History Center.