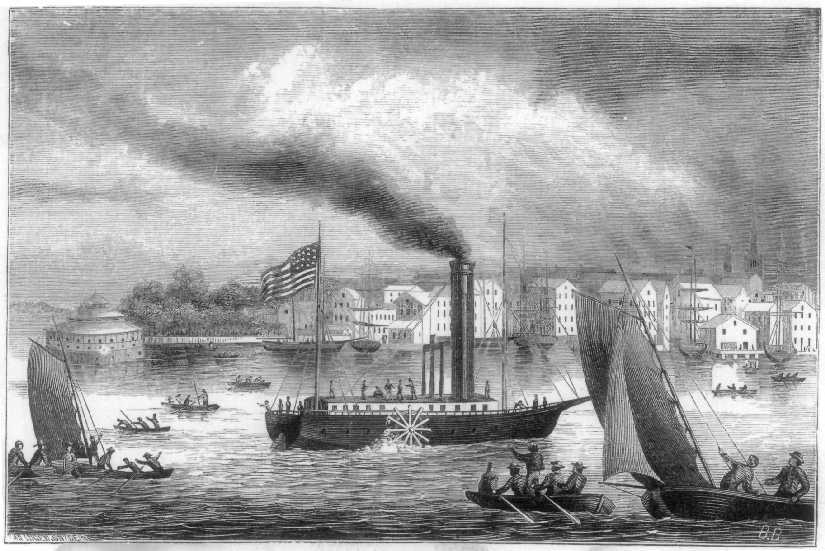

A folk painting on display in the History Center’s Pittsburgh: A Tradition of Innovation exhibit captures one of Pittsburgh’s most important early innovations. On Oct. 20, 1811, the steamboat New Orleans set off from this place on a journey of more than 1,800 miles down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Funded by Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston, the New Orleans represented a vision of the future. When the boat landed at its namesake city on Jan. 10, 1812, it proved that steamboats could survive the journey on America’s western rivers. Within a decade, steamboats would link the nation’s interior like nothing had before.

The artist took some license presenting this view of the trip. The real boat probably looked a bit more like a sailing ship. The familiar shape of a multi-deck steamboat arose over time as builders adapted their craft to the needs of the rivers and industries they supported. The steamboat was so new in 1811 that there was no established model; the painting was likely created years later.

But it does capture the excitement of the journey. Small figures wave from the shore and one person runs alongside, perhaps trying to catch up to the boat. Figures on board wave back, unfazed by the black smoke billowing from the stack overhead. They have no idea of the trip that lies ahead.

The New Orleans overcame much to reach its destination. Surely its stalwart builder, Nicholas Roosevelt, and his equally intrepid wife Lydia (eight months pregnant at the start of the journey), had their moments of doubt. But Roosevelt, like his great-grand-nephew Theodore decades later, possessed an unrelenting spirit of exploration. The New Orleans persevered through a combination of skill, luck, and sheer doggedness.

Just consider four of the hurdles they overcame along the way:

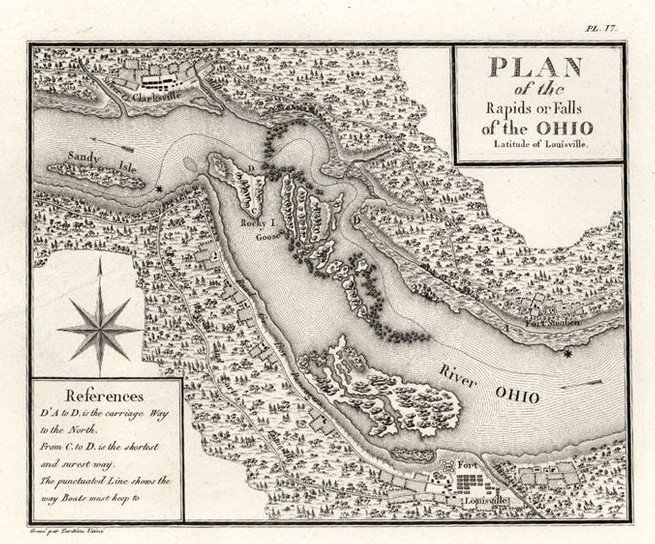

Low water at Louisville

The New Orleans did not get far before Nicholas and Lydia faced their first challenge. By the evening of their fourth day, they reached Louisville. There, they found the water level too low for the New Orleans to navigate through the notorious Falls of the Ohio. This series of ridges, caused by the Ohio River dropping 26 feet over a rise in the limestone bedrock, was the most serious obstacle in the first stage of the trip. There was nothing to do but wait. The New Orleans stayed put through November. This proved just a well, since Lydia gave birth to the couple’s second child while they were waiting in Louisville. As they say, timing is everything.

A fearsome new creation

The arrival in Louisville also gave the New Orleans crew a taste of how their new technology might be received by those less familiar with the sights and sound of steam. The New Orleans pulled in around midnight, and the roar of the boat’s steam power proved so unsettling that crowds rushed down to the wharf to see what was happening, sure something terrible had occurred.

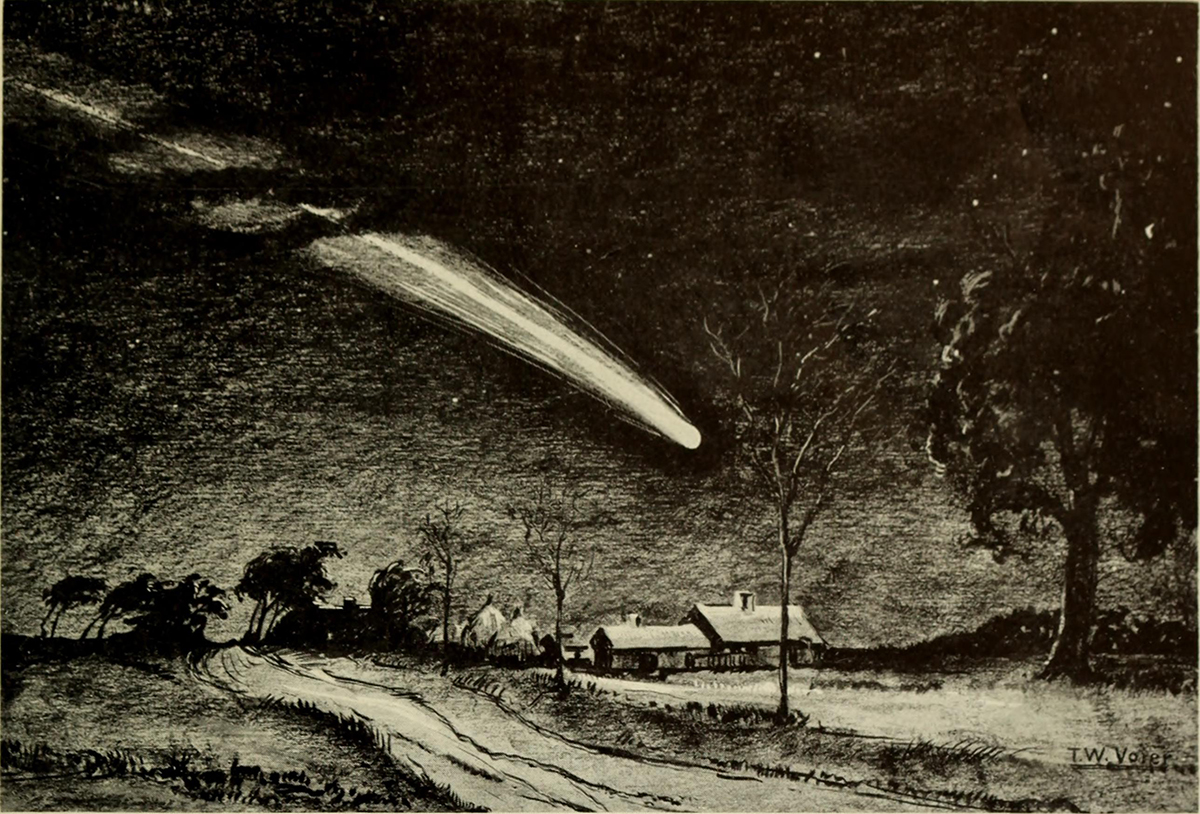

All along the boat’s trip, eyewitness accounts recorded that some people reacted to it with fear. Native American tribes – already provoked by U.S. expansion into Indian Territory and the Battle of Tippecanoe in November – were sometimes openly hostile. The boat’s journey also coincided with the appearance of the Great Comet of 1811 over North America, for some, one more sign that the whole endeavor foreshadowed disaster. Some even believed that the noises from the steamboat were the sound of the comet crashing into the Ohio River.

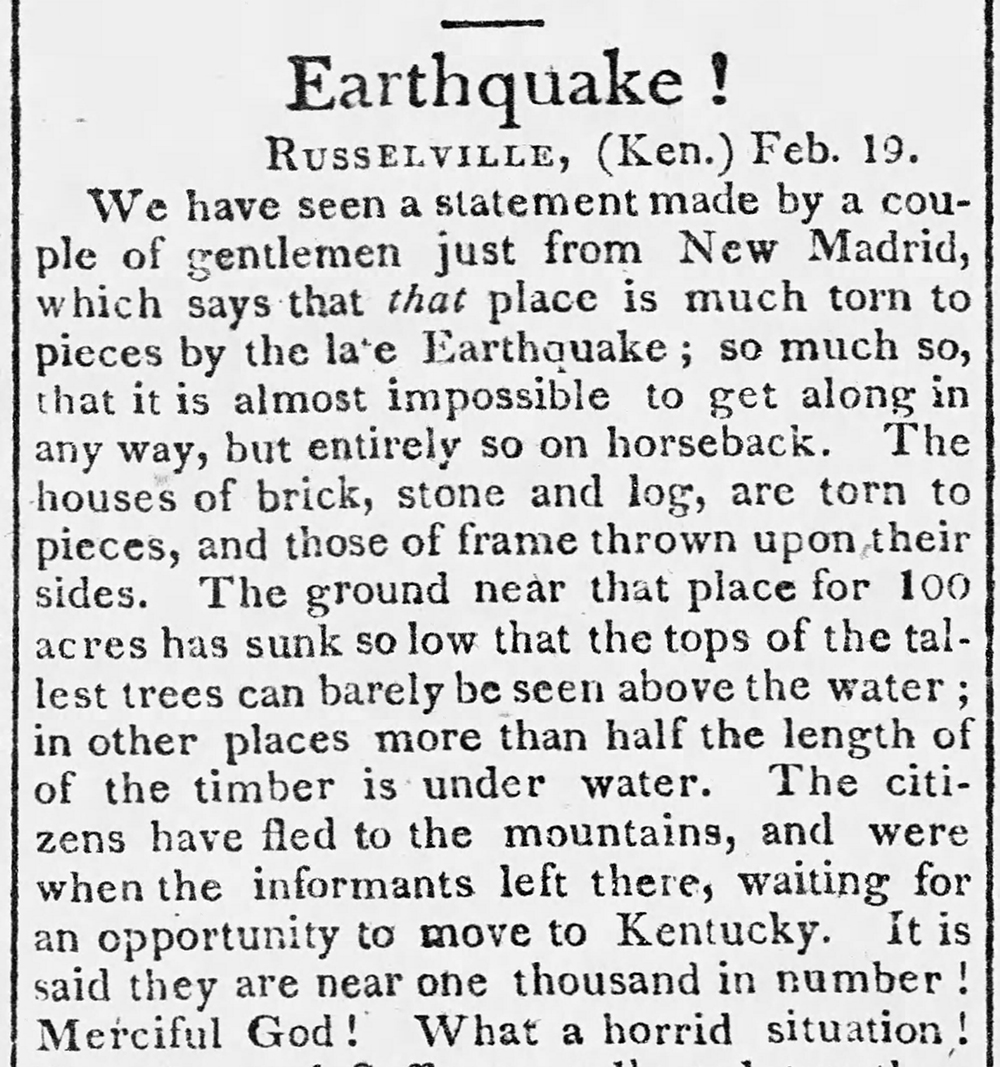

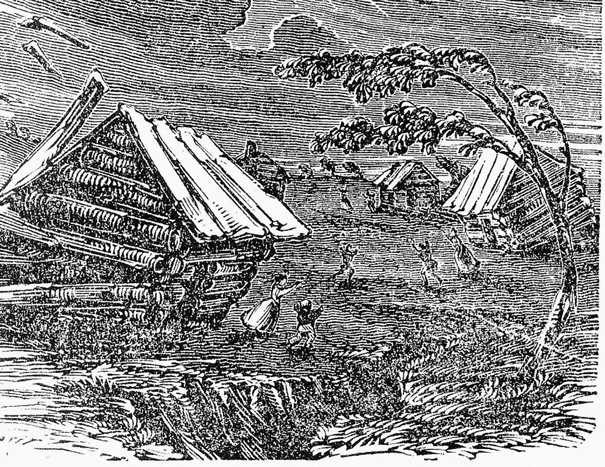

The New Madrid Earthquakes

To make matters worse, the New Orleans’ journey took place during another more terrifying historical milestone. Between Dec. 16, 1811 and Feb. 7, 1812, a series of earthquakes struck along the New Madrid fault line near the Mississippi River in Missouri and Arkansas. With magnitudes ranging from 7.5 to 8.0, they remain the strongest earthquakes ever to hit the eastern U.S. The impact was felt as far away as Pennsylvania and Massachusetts.

The Mississippi temporarily ran backwards. Two waterfalls briefly emerged as the river’s bed shifted to accommodate the tremors. Whole islands disappeared while new ones were created. Channels were blocked by debris. Existing navigational charts became meaningless. Boats traversing the area braved miles of utterly uncharted waters.

Miraculously, the New Orleans made it through the earthquake zone. Avoiding the banks, where trees continued to fall into the river, the boat somehow navigated through the disappearing islands, roiling waters, and unstable riverbed to reach its destination during the worst period of seismic activity the region has ever experienced.

The Infernal Snag

The earthquakes also intensified a danger always present on the river: snags – sunken trees whose twisted roots and branches could impale a boat and easily take it to a watery grave. The Mississippi offered plenty of them in the best of times. But now, with the activity from the New Madrid fault, the situation was far worse. One writer sent a letter (published in the Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette on Feb. 18, 1812) to Zadok Cramer and the men who published the Navigator river guide. He described the situation: “the river burst and shook up hundreds of trees from the bottom . . . all turned roots upward and standing up stream in the best channel and swiftest water, and nothing but the greatest exertions of the boatmen can save them from destruction in passing those places.”

Would those small waving figures on the New Orleans have thought twice had they known of the challenges that lay ahead?

Maybe. But then again, probably not. Those who pushed the creation of the steamboat were already reaching beyond the technical limits of the day. Traversing the Ohio and Mississippi by steam to reach Louisiana was almost akin to envisioning a trip to the moon. Once Nicholas Roosevelt and his crew set off from Pittsburgh, it probably would have taken far more than a few earthquakes and some sunken trees to dissuade them from their course. Their journey had already taken them too far to turn back.

For Further Reading

For accounts of the New Orleans’ voyage:

- John H. B. Latrobe, The First Steamboat Voyage on the Western Waters, Maryland Historical Society, 1871.

- “Steamboat Adventure: Down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers with Nicholas and Lydia Roosevelt, 1811-1812.” A site including multiple excerpts from original letters, newspaper reports, etc., Sponsored by the Rivers Institute and the History Department of Hanover College, Hanover, Ind.

For accounts of the New Madrid Earthquake:

- Elizabeth Rusch, “The Great Midwest Earthquake of 1811,” Smithsonian Magazine, December 2011.

- The University of Memphis Center for Earthquake Research has compiled a great listing of eyewitness accounts from the New Madrid earthquake sequence.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.