The last time Hamilton came to Pittsburgh, he wasn’t quite as popular.

In fact, he was arguably one of the most hated men in Western Pennsylvania in the late 1700s, thanks to his liquor tax that sparked the Whiskey Rebellion.

As Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hit Broadway musical “Hamilton” returns to Pittsburgh, we’re taking a look at some of the historical connections between Western Pennsylvania and the founding fathers portrayed in this wildly popular musical.

Before Alexander Hamilton made his way to Pittsburgh, George Washington had his own formative experiences in the region. Some of those experiences took place in 1754, when 22-year-old Washington was involved in the skirmish at Jumonville Glen, in which French soldiers were ambushed and their leader was killed by Washington himself. This led to the Battle of Fort Necessity, also called the Battle of the Great Meadows, where Washington had to surrender for the first and only time.

Washington signed a surrender document written in French, unwittingly accepting responsibility for the assassination of the French envoy Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. This defeat was one of the first battles in the conflict that would eventually be known as the French and Indian War. (Visit the History Center’s Clash of Empires: The British, French & Indian War, 1754-1763 exhibition to learn more.)

In Miranda’s retelling of the story, Washington’s character in “Hamilton” references his experiences in the French and Indian War (with a bit of creative license) during the song “History Has Its Eyes On You,” as Hamilton prepares to lead troops in the Battle of Yorktown:

[Washington to Hamilton]

“I was younger than you are now

When I was given my first command.

I led my men straight into a massacre.

I witnessed their deaths firsthand.”

The Battle of Yorktown would ultimately lead to an American victory in the Revolutionary War.

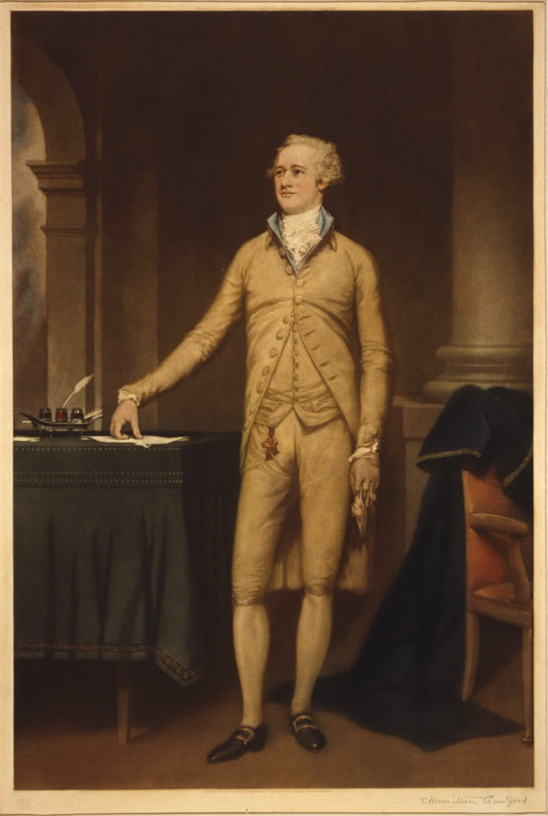

Alexander Hamilton became the first American Secretary of the Treasury and a member of President Washington’s cabinet. In 1791, Hamilton proposed an excise tax on distilled liquor – the first tax on an American-made product – to help pay debts from the Revolutionary War.

In “Hamilton,” Thomas Jefferson’s character predicts trouble in the song “Cabinet Battle #1” when he alludes to Hamilton’s proposed tax:

[Jefferson to Cabinet]

“Stand with me. In the land of the free.

And pray to God we never see Hamilton’s candidacy.

Look, when Britain taxed our tea, we got frisky.

Imagine what gon’ happen when you try to tax our whiskey.”

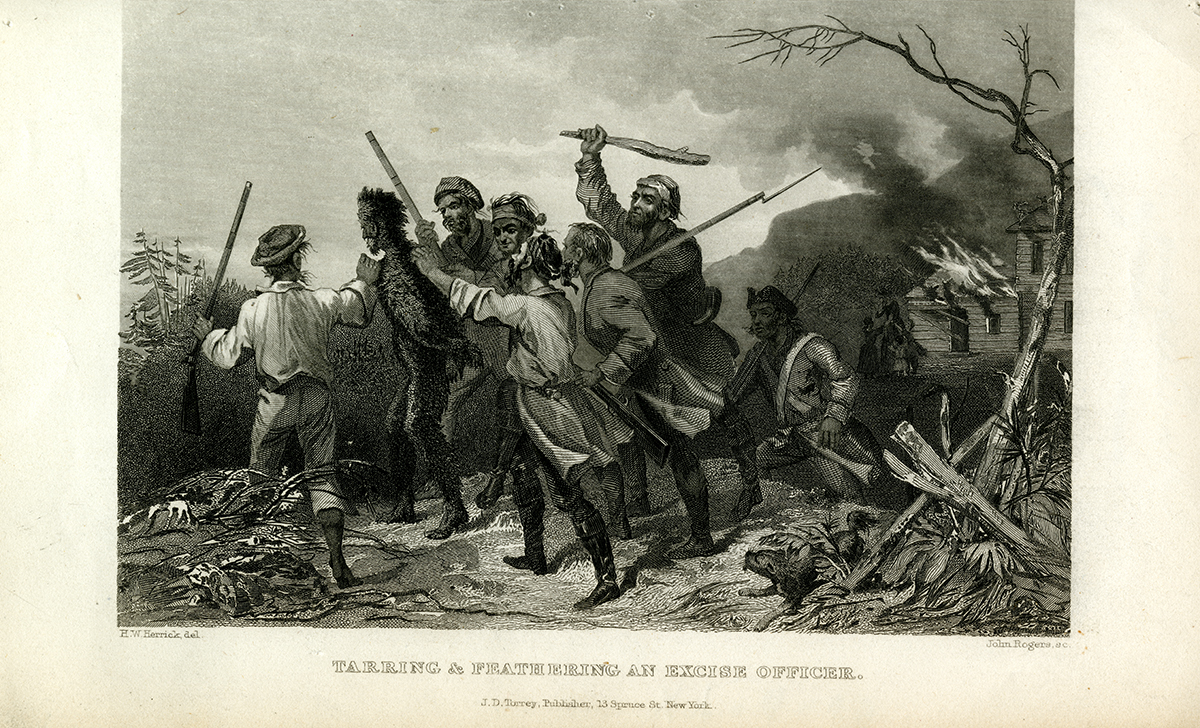

Congress passed the legislation, and farmers in Western Pennsylvania refused to pay the tax because they believed it unfairly hurt small-scale farmers. Their protests soon turned violent, as rebels tarred and feathered tax collectors and set fire to the home of John Neville, the region’s tax collection supervisor.

The government had to act.

At Hamilton’s urging, Washington rallied a militia force of nearly 13,000 men and led them toward Western Pennsylvania. Washington, Hamilton, and the troops got as far as Bedford, Pa., when they got word that the rebels had disbanded. Washington turned around, but Hamilton continued on to Pittsburgh.

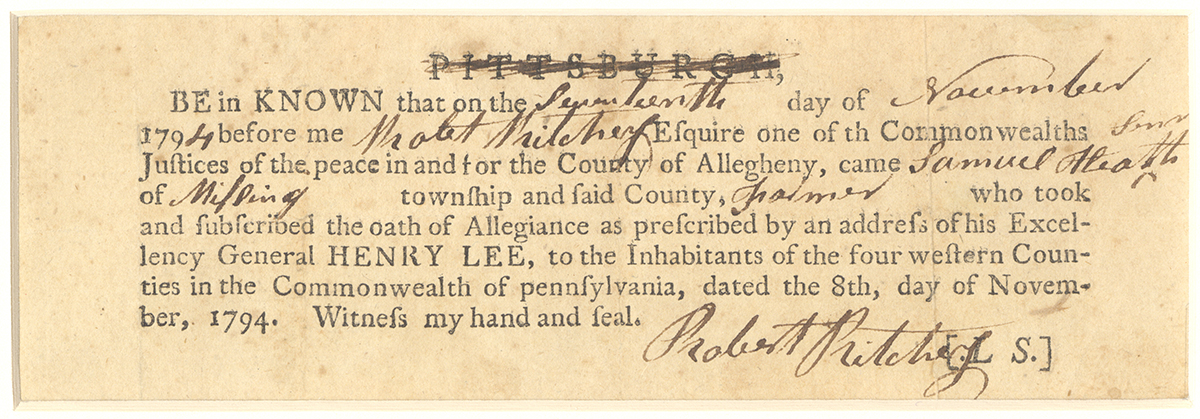

When Hamilton and the militia reached the Forks of the Ohio on Nov. 13, 1794, they arrested hundreds and charged them as traitors. After this “Dreadful Night,” most of the men were released while some had to stand trial in Philadelphia. They were later pardoned by the president.

Because of Hamilton’s role in the creation and enforcement of the excise tax, ill will toward the founding father remained in Western Pennsylvania long after he left in late November of 1794.

Fast forward a few centuries, and that ill will has dissipated. Enough so that tens of thousands of Western Pennsylvanians are excited for the hit musical based on Hamilton’s life now showing at the Benedum Center for Performing Arts.

And the Pittsburgh connections don’t stop with Hamilton’s 1794 visit. Original members of the “Hamilton” cast and creative team are Carnegie Mellon University alumni: Leslie Odom, Jr. (Aaron Burr), Renée Elise Goldsberry (Angelica Schuyler), and Scott Wasserman (Ableton Programmer), as well as former CMU costume design faculty member Paul Tazewell (costume designer).