“No. We were not Rosie the Riveter. We welded ships. Rosie got all the attention. No one even gave us a name.

Anne Jurjevic Thomas, welder at Dravo during World War IIi

Today “Rosie the Riveter” symbolizes all American women who worked in the nation’s defense industries during World War II. Congress confirmed this when the Senate passed a bill authorizing the Rosie the Riveter Congressional Gold Medal at the end of 2020.ii

“Rosie” first appeared in a song written in 1942 that began hitting radio airwaves that November.iii Her appeal increased over time, especially as public recognition of the character merged with the wildly popular Westinghouse “We Can Do It” poster. This remarkably resonant symbol has proven adaptable to almost limitless interpretations. Today, “Rosie” is everywhere.

More than Rosie

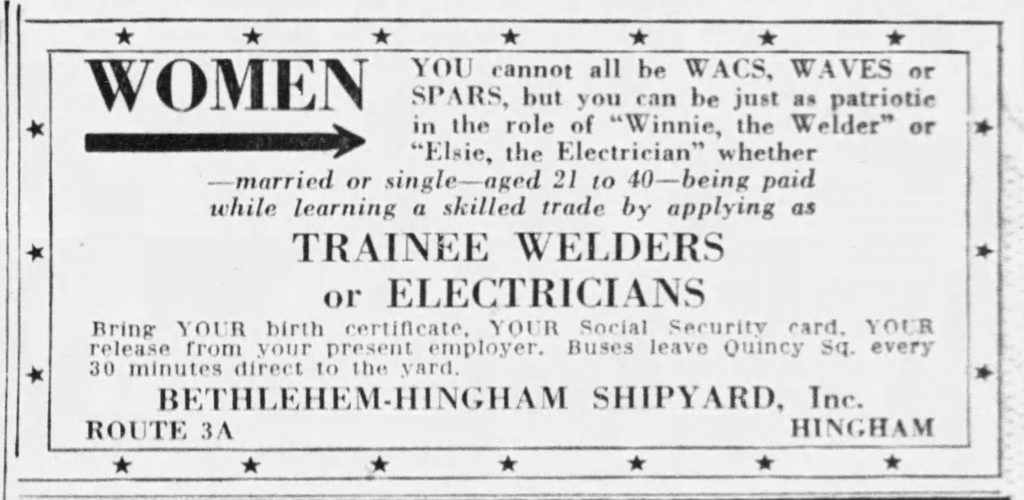

Back in the 1940s, some women would have reminded us that they were not all riveters. Women filled many industry roles during the war. Reflecting this, other characters appeared, some in response to “Rosie.” Garbed in work pants and goggles, “Susie the Steelworker” debuted at a Carnegie-Illinois steel plant in Gary, Ind., in March 1943.iv A Boston shipyard recruited “Elsie, the Electrician.”v One writer advocated for “Typewriting Tess.”vi A California newspaper reported a distraught “Aircraft Annie” lamenting “Rosie’s” rise.vii Even Canada saluted “Ronnie, the Bren Gun Girl.”viii (The Bren gun was a light machine gun.) Such personifications attested to the wide experiences of real women defense workers and underlined the value of labels as recruiting tools: soundbites for the 1940s.

“Soldiers without guns,” recruiting poster including a woman welder, 1944. Art by Adolph Treidler, U. S. Government Printing Office. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

Meet Winnie the Welder

Aside from Rosie, the most widely used name was “Winnie the Welder.” The idea possibly first appeared in a comedy routine offered by entertainer Jack Marshall at the Belmont Plaza Hotel in New York City in August 1942. According to Ed Sullivan, Marshall debuted a “daffy tune” called “Winnie the Welder, Queen of the Smelter, Defense Plant No. 9.”ix It is not clear what happened to the song. But the phrase gained traction and “Winnie the welder” sometimes accompanied “Rosie” in newspaper coverage regarding women workers.

Advertisement for the Bethlehem-Hingham Shipyard, seeking “Elsie, the Electrician” and “Winnie, the Welder,” 1943. (Boston Globe, July 17, 1943)

Pittsburgh’s Women Welders

For Pittsburgh, women welders represented a significant World War II story. Courses for female welding students began appearing in fall 1942. Excitement and skepticism greeted them. The Pittsburgh Press described women “begging” to get into classes at South Vocational High School, reminding readers that women welders proved their merit during World War I.x The paper also cited concerns raised by the Women’s Bureau of the U.S. Labor Department. Reports warned that welding was a specialty with limited opportunities for women. A course instructor cautioned that some industrial plants would be unsuitable for women, especially shipyards, where welding entailed “arduous climbing.”xi

LSTs built by Women

Such concerns failed to stop thousands of Pittsburgh-area women who went to work building LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) at the Dravo Corporation and American Bridge Company. Many were welders. They included sisters Vera (Vee), Julie, and Ann Jurjevic, three of six daughters in a family whose Croatian-born parents settled in the North Perry neighborhood. Vee, the oldest, received training first and started at Dravo in May 1943. Welding allowed her to fulfill a patriotic duty and earn more than her previous job as a maid. Her sisters followed. Julie and Ann attended welding school together before starting at Dravo in July 1943. Eventually, all three worked in the same yard.xii

Chain employment through family or social ties was common. Women learned of jobs through word of mouth and received assistance in making connections. Entering the factory floor for the first time, many welcomed the presence of companions and commuting partners. With far fewer cars on the road, some women commuted as much as two hours each way to reach Dravo’s Neville Island shipyard

No Quitting on D-Day

Women like Mrs. Richard “Bessie” McCarroll of McKees Rocks illustrated the determination of these new welders. The Pittsburgh Sun Telegraph featured her with fellow Dravo welder Mrs. Alvin Mevers on June 2, 1944. With a European invasion looming, a survey asked such women, “war brides” with husbands overseas, how they would respond when the event happened. Would they go home? Collapse in hysteria? Bessie McCarroll replied, “Quit on D-Day? Nothing doing.” Like the rest, she would be “right in there pitching,” helping to win the war of production so their husbands could return home.xiii

Such queries remind us that these women did their duty while balancing fears about loved ones overseas and mastering skills and a work environment that would have been unthinkable a few years earlier.

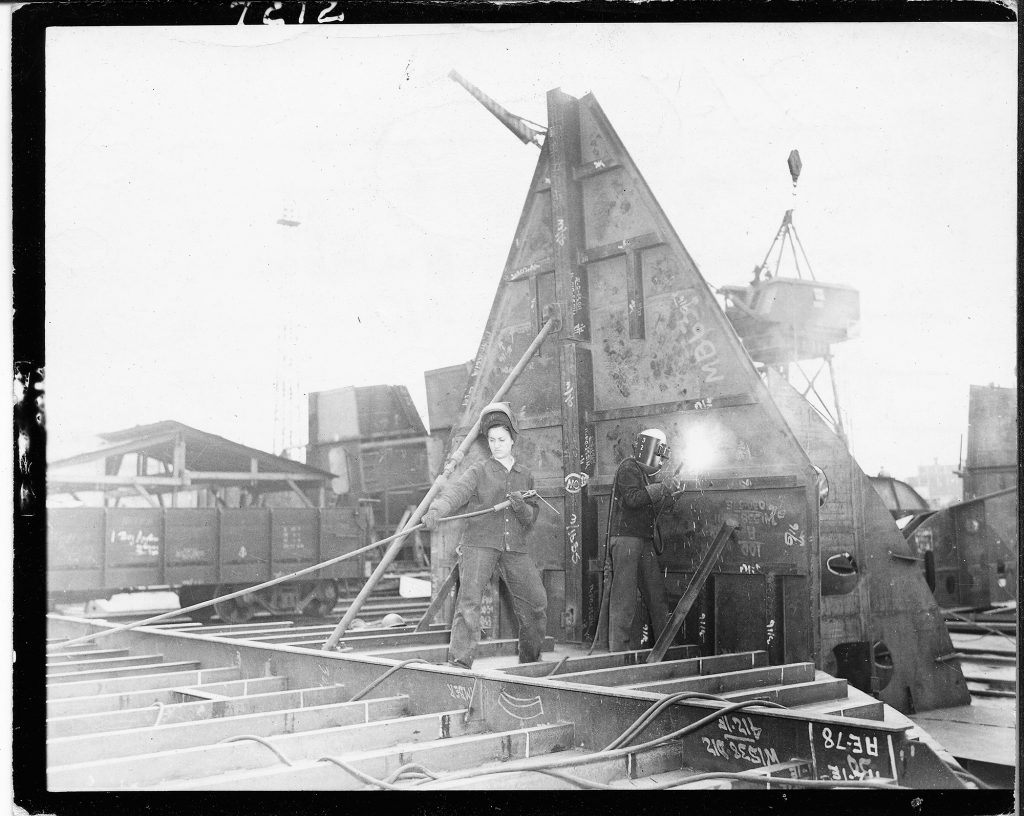

Mrs. Bessie McCarroll (L) and Mrs. Alvin Mevers (R) at work on an LST at Dravo, June 2, 1944. Dravo and American Bridge trained thousands of women to be welders during the war to help with the urgent production demands of the LST program. Mrs. McCarroll and Mrs. Meyer were interviewed and photographed by the local press in the days leading up to D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944. Dravo Corporation Photographs, MSP 288, Detre Library & Archives.

What happened to Winnie?

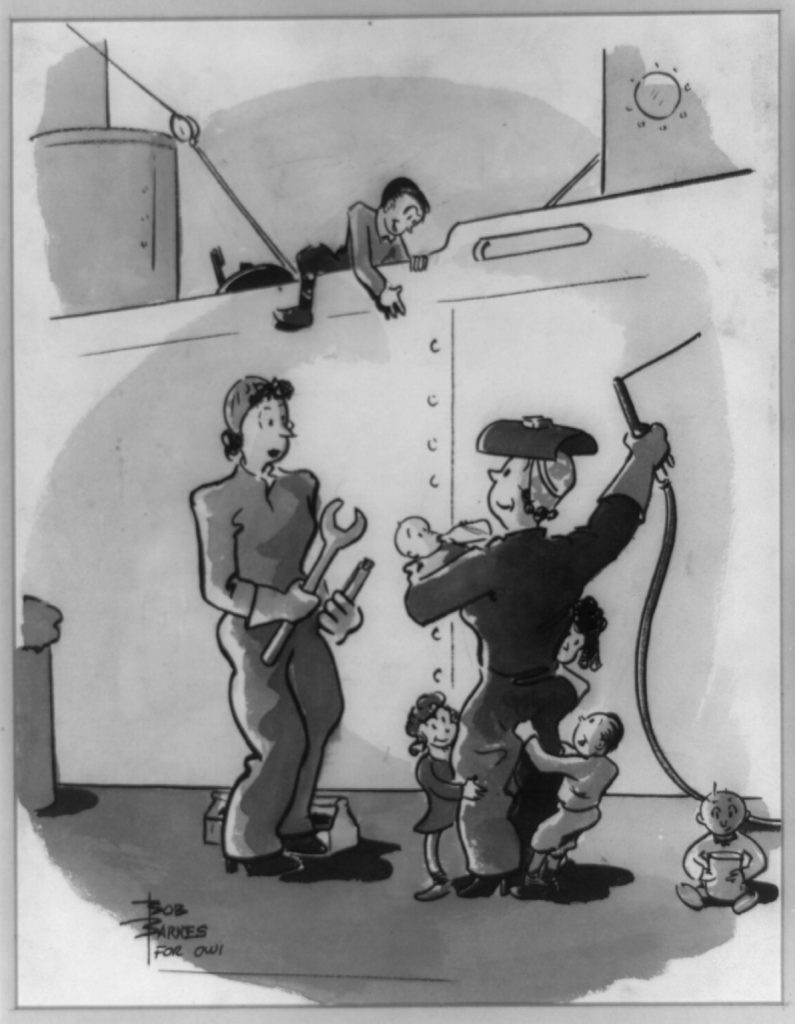

With her distinctive helmet, the woman welder symbolized a changed world. She became a familiar figure, appearing in advertisements, recruiting posters, and cartoons. But over time, her stature in popular imagination dimmed. By 2004, when Ann Jurjevic Thomas talked with her daughter Kathleen about what she did during the war, Ann recalled that no one gave the welders a name. “Winnie the welder” had largely disappeared.

What happened? From the start, “Winnie” never received as much coverage, a situation magnified when recorded versions of “Rosie the Riveter” spawned nationwide popularity. Magazine covers and movies gave Rosie lasting visual appeal. The fact that “Winnie’s” helmet covered her face or complicated graphic layouts did not help.

Women welders also may have garnered the wrong kind of notoriety. A column in a Brooklyn, N.Y., newspaper from July 1943 suggested this:

“There was a time when any radio comedian could throw his studio audience into gales of laughter by referring flippantly to women welders in the nation’s shipyards. In fact, the custom of twitting the ladies for assuming this traditionally masculine task got so widespread that the fickle radio listeners got fed up and refused to titter any more.”xiv

In the fine balance between caricatures that celebrated and those that revealed darker fears about a world turned upside down, “Winnie” may have represented a step too far. In any event, thousands of women disregarded the “twitting” and simply got on with the job.

National Rosie the Riveter Day

So, when National Rosie the Riveter Day rolls around on March 21, celebrate her legacy. But also give a thought to “Winnie” and think about the varied experiences of the women who served in the nation’s defense industries during the war. Raise a toast to the riveters, electricians, inspectors, mechanics, chemists, drill press operators, steelworkers, typists, and yes, the welders too.

For further reading

Kellie B. Gormly, “Rosie the Riveter Gets Her Due 75 Years After the End of World War II,” Smithsonianmag.com, December 8, 2020. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/rosie-riveter-gets-her-due-75-years-after-end-world-war-ii-180976474/

Kathleen Thomas Don’t Call Me Rosie, The Women who Welded the LSTs and the Men who Sailed on Them. Tigard, OR: Thomas/Wright Inc., 2004.

Citations

i Kathleen Thomas, Don’t Call Me Rosie, The Women Who Welded the LSTs and the Men Who Sailed Them. Tigard, OR: Thomas / Wright Inc., 2004, p. 4.

ii The House of Representatives passed it in 2019.

iii While the song was not recorded commercially until 1943, it was heard live performed as a novelty tune as early as November 24, 1942, when it was included on the Ozzie and Harriet show: “KFAM Program Hi-Lights,” St. Cloud Times (St. Cloud. MN), November 24, 1942.

iv “‘Steeler Susie’ in Plant Debut,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, March 21, 1943.

v Recruiting advertisement for Bethlehem-Hingham Shipyard, Inc., Boston Globe, July 17, 1943.

vi E. V. Durling, “Typewriter Tess Vs. Riveting Rosie,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, January 14, 1944

vii Erskine Johnson, “Aircraft Annie opens War on Rosie the Riveter,” Ventura County Star-Free Press (California), December 10, 1942.

viii Moriah Campbell, “The Bren Gun Girl,” Canadashistory.ca, July 18, 2017. Available online at https://www.canadashistory.ca/explore/military-war/the-bren-gun-girl

ix Ed Sullivan, “Little Old New York,” Daily News (New York, NY), August 10, 1942. Marshall, later known for television themes such as that for “The Munsters,” was hailed as the “new bright light” of the Belmont Plaza’s Glass Hat Room review. See: “The Follow Up Review,” The Billboard, August 8, 1942, pg. 13.

x Douglas Naylor, “Victory Belles,” Pittsburgh Press, October 7, 1942.

xi Ibid.

xii The Heinz History Center holds a small collection of Vera’s papers, see: Detre Library and Archives, Vera M. Jurjevic Drab Collection, 2001.0217. Ann’s perspective can be found in: Thomas, Don’t Call Me Rosie, 2004.

xiii Mary Somers, “War Brides Pledge Work on D-Day,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, June 2, 1944.

xiv “The Women Welders Make Good,” Brooklyn Citizen (NY), July 26, 1943.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.