An October post featuring Pittsburgh businesswomen garnered such great response that it deserved a follow up. These efforts remind us why celebrations like the 19th Amendment Centennial need to go forward despite pandemic challenges and why projects such as the History Center’s Women Forging the Way initiative and the Smithsonian’s Because of Her Story are crucial. Calls to acknowledge women’s contributions in American history go back more than 200 years. On multiple occasions, a flurry of activity prompted by a few individuals gave way to a familiar silence. Today’s projects offer curators and archivists another chance to preserve these stories and raise awareness for future generations.

Women of the Revolution

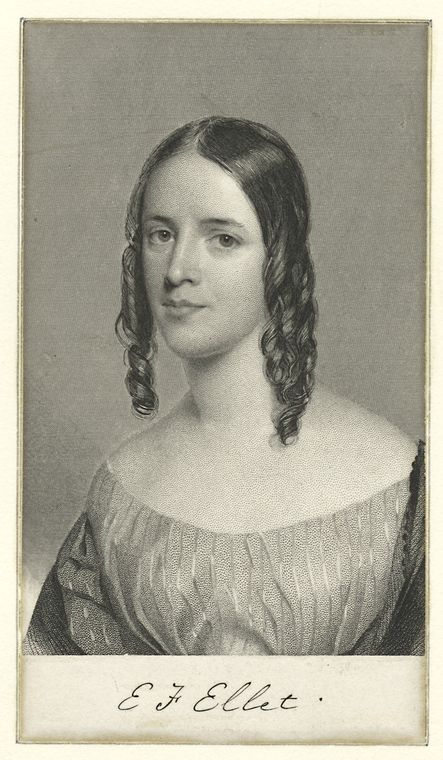

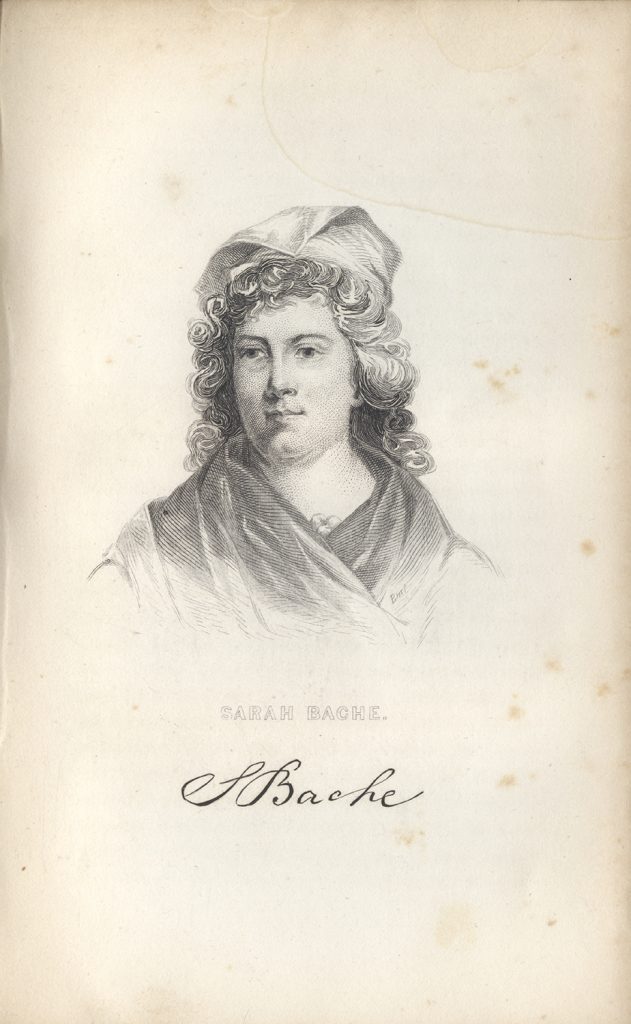

American author Elizabeth Ellet issued her appeal for the cause in the 1840s. Worried that women’s contributions to the nation’s founding were being lost with the passing of the Revolutionary generation, Ellet came up with her own solution. Responding to the popularity of illustrated biographies, she wrote and published “Women of the American Revolution” (1848 – 1850). Seeking out personal diaries, letters, and memories, she emphasized the stories of well-known heroines such as Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren. But Ellet also highlighted lesser-known women whose domestic sacrifices kept their families going while their husbands served in the war.[1]

Stories written out of history

Despite such efforts, Ellet’s fears proved justified. As the discipline of history began professionalizing in the late 1800s, men became its primary recorders, especially members of the social and economic elite with enough money and time to make that work possible. They celebrated what they valued. They interpreted the world through the lens of Victorian expectation regarding the separation of labor and gender roles. Stories that did not fit this model were minimized.

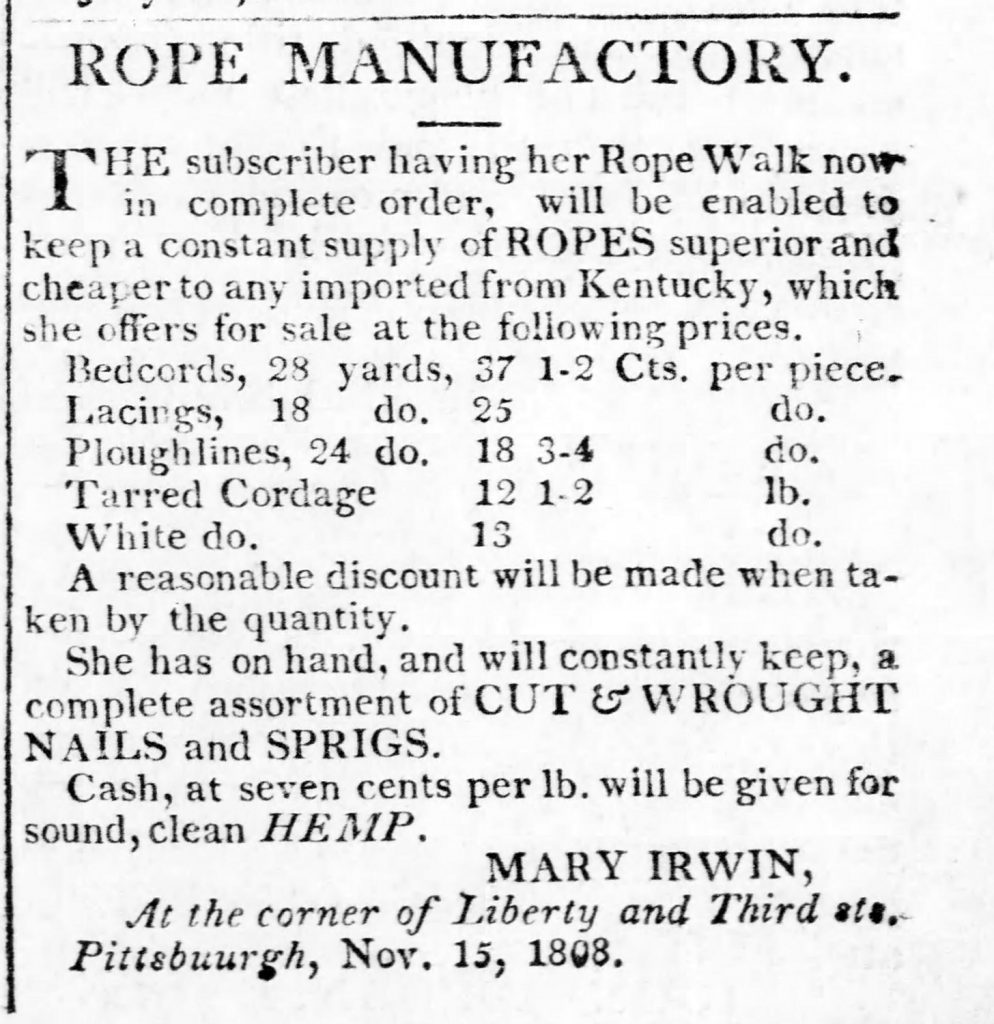

Pittsburgh’s now-celebrated rope manufacturer Mary Pattison Irwin was a good example. An Irish immigrant, Irwin arrived here with her husband John in the 1780s. By 1794, they started a successful rope-making business that lasted for multiple generations. While the business was originally registered as John Irwin & Wife, Mary did most of the work due to her husband’s fragile health. She continued after he died and carried on through 1813, when she signed it over to her son. Her achievements were remarkable, including documented contributions to Commodore Perry’s fleet for the Great Lakes campaign during the War of 1812.

Today Mary’s story has been rediscovered and told in videos, podcasts, and articles. A few are listed below. But how did someone like Mary Irwin disappear in the first place? The pattern emerged over time. In 1886, Judge John E. Parkes, writing in his book “Recollections of Seventy Years and Historical Gleanings of Allegheny, Pennsylvania,”acknowledged Mary’s role in the business, calling her a woman with “indomitable courage and perseverance,” endowed with “rare business qualifications.”[2] But he focused more on the role of her son John and his sons. Their larger rope works, built on 10 acres by the West Commons after 1813, lasted until 1858, lingering in living memory of historians writing in the 1880s. That was the story that lasted. By the time another local historian, Charles Dahlinger, wrote about Irwin’s rope works in his article “Old Allegheny” in the Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine in 1918, he focused solely on John’s business after 1813. Mary Irwin was gone.[3]

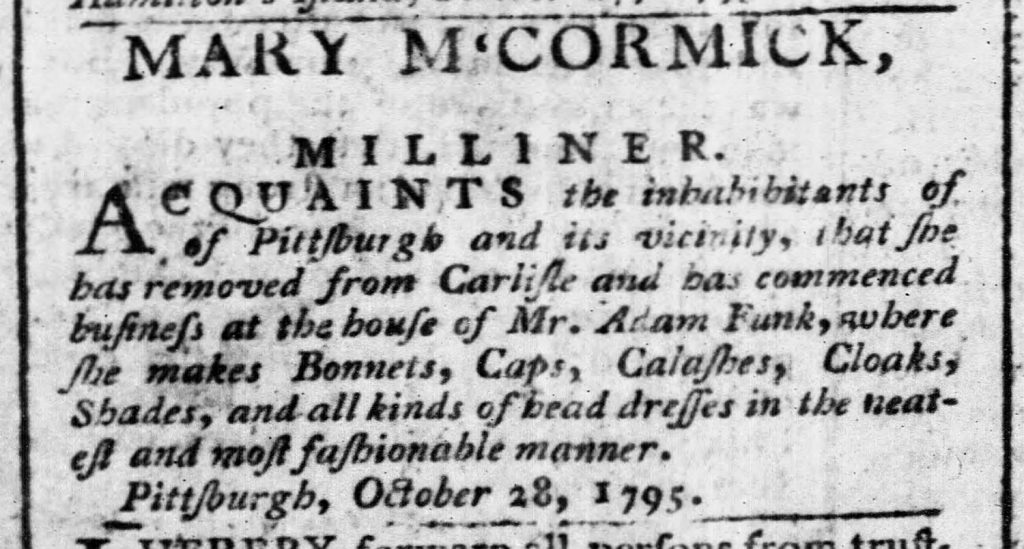

How many times was a similar pattern repeated? From milliners and teachers to midwives, women who helped shape the lives of their communities became footnotes to history.

Multiple calls for reform

The process was relentless despite repeated reminders to the contrary. On Dec. 10, 1885, Pittsburgh teacher and outspoken women’s columnist Bessie Bramble (a pseudonym for Mrs. E. A. Wade) presented a paper to the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania titled “The Deeds of American Women.”[4] Angered that “in our American school history the achievements of women are studiously ignored . . .” Bramble outlined women’s actions during the American Revolution and the Civil War and discussed reformers such as Dorothea Dix and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Criticizing the mindset that conveyed there “were no Pilgrim mothers” just a “band of persecuted men,” Bramble urged the Historical Society to extend “all advantages, all honors, all records” to women, hoping that the “forgotten women” would be “evermore remembered in the annals of Western Pennsylvania.”[5]

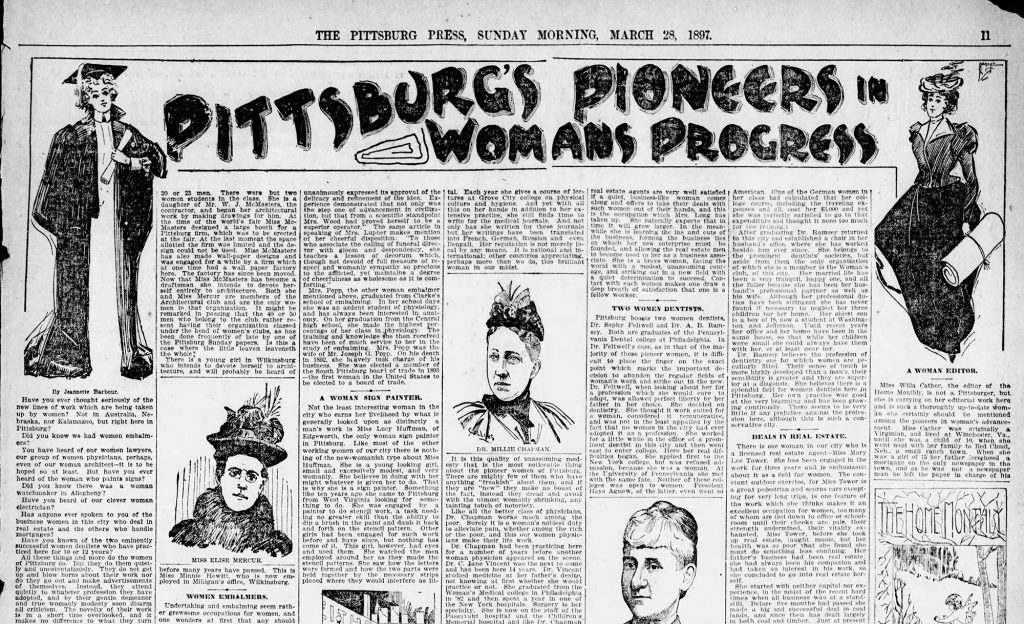

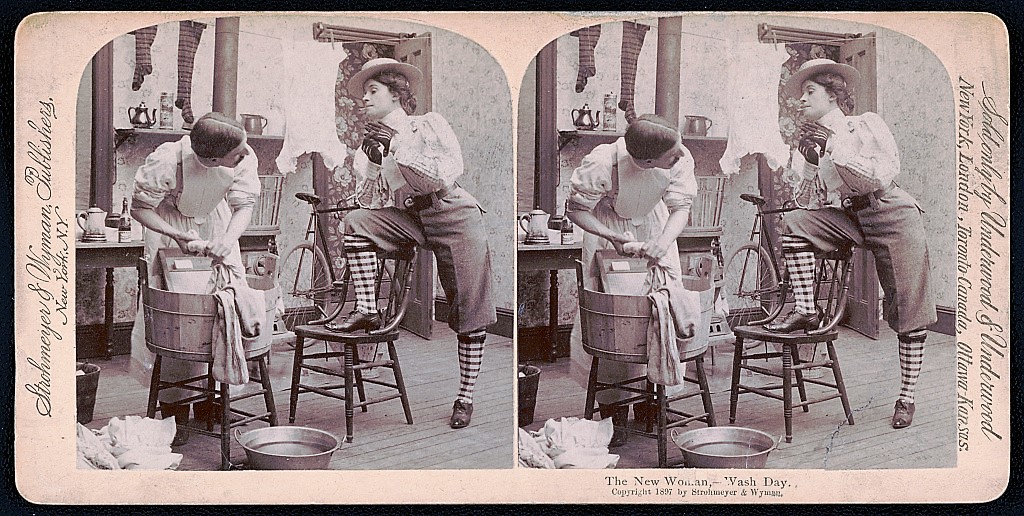

On March 28, 1897, Pittsburgh Pressreporter Jeanette Barbour offered a full-page article celebrating “Pittsburg’s Pioneers in Womans Progress.” She profiled nearly 30 professional women. Of special note was a young editor who had arrived the previous July to work for The Home Monthlymagazine. Willa Cather, Barbour noted, would be “worth watching.”[6] But of the many women in the article—lawyers, sign painters, dentists, embalmers, a watchmaker, architects, a mortgage agent, and nine physicians—few gained lasting recognition. Cather achieved fame for her novels set on the Great Plains. Electrician and engineer Bertha Lamme became known for her work with George Westinghouse. (Read more about her career in this blog post.) Physician Millie J. Chapman, MD, went on to a long and remarkable career, serving residents of Pittsburgh and later in her hometown of Springboro in northwestern Pennsylvania.[7]

Perhaps with a little luck, collections and stories related to some of the other women may yet be found. But what if someone had gathered that material in the 1890s? How much fuller would Pittsburgh’s historical record be today?

Filling the Gap

The situation finally began to change on a permanent basis in the 1970s. A wider social transformation and the dawn of academic women’s history programs began gradually raising the profile of women’s stories. Today’s initiatives represent another chance to balance the historical record. Some artifacts and archives may be lost for good, but the stories of women such as Mary Pattison Irwin can be recovered. The impact of women in recent decades can be collected now.

As we look forward to 2021 and the resumption of the 19th Amendment Centennial activities postponed due to the pandemic, it is important to get the word out and continue advocating for a more equitable portrayal of women’s contributions and a wider telling of so many stories that remain to be told.

Leslie Przybylek is senior curator at the Heinz History Center.

[1] Ellet was a controversial figure in her lifetime. Her reputation based on very public feuds with people such as Edgar Allan Poe probably limited the impact of her serious work, see: Gretchen Ferris Schoel, “In Pursuit of Possibility, Elizabeth Ellet and the Women of the American Revolution,” M.A. Thesis (William & Mary College), Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625717.

[2] John E Parke, Recollections of Seventy Years and Historical Gleanings of Allegheny, Pennsylvania (Boston: Franklin Press) 1886: 194.

[3] Charles W. Dahlinger, “Old Allegheny,” Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine 1:4 (October 1918): 181.

[4] “Bessie Bramble’s paper read before the Historical Society,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 11, 1885. “Bessie Bramble” was a pseudonym for Mrs. E. A. Wade, whose identity was reputedly secret. But the Post-Gazette and the Historical Society clearly knew her real name, as it was acknowledged in the 1885 article.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Jeanette Barbour, “Pittsburg’s Pioneers in Womans Progress,” The Pittsburg Press, March 28, 1897, pg. 11. This is during that odd interlude where Pittsburgh lost its “h.”

[7] Later in her life, Dr. Chapman received extensive newspaper coverage in both Pittsburgh and her home community of Springboro, Pa., (about 30 miles south of Erie, Pa.). See for example: June Greene, “Woman who overcame tradition and prejudice lived to have respect of colleagues,” The Pittsburgh Press, August 3, 1939.

For More Information

Special thanks to Gloria Forouzan for her referral to Mary Pattison Irwin and suggestions for additional resources.

To learn more about Mary Pattison Irwin, check out these resources:

Katie Blackley, “Rope Magnate Mary Irwin operated one of the city’s largest industries,” WESA.fm, March 19, 2019. Available online.

“Notable Pittsburgh Women: Mary Pattison Irwin,” City of Pittsburgh YouTube channel, 2019. Available online.

“The Ropemaker Mary Pattison Irwin,” What’shername.com podcast, December 30, 2019. Available online.

To read more about Bessie Bramble, see:

Emilia S. Boehm, “Elizabeth A. Wade, a.k.a. ‘Bessie Bramble’,” Western Pennsylvania History (Fall 2008). Available online.

Kelly I Shaffer, editor, “Bessie Bramble: The Secret Suffragette,” Western Pennsylvania History, 69:4 (October 1986): 383-394. Available online.

To learn about Willa Cather’s time in Pittsburgh, see:

Kathleen Derrigan Byrne, Willa Cather’s Pittsburgh Years 1896-1906,” Western Pennsylvania History 51:1 (January 1968): 1-15. Available online.

Peter Oresick, editor, The Pittsburgh Stories of Willa Cather (Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Mellon University Press), 2016.

To find more on Dr. Millie J. Chapman, see:

“Millie J. Chapman – Notable Dollar Bank Customers from the Past,” Dollar Bank Heritage Center, ©2020. Available online.

Gertrude Gordon, “Pioneer in Medicine forced to struggle to win position,” The Pittsburgh Press, March 23, 1924.

June Greene, “Woman who overcame tradition and prejudice lived to have respect of colleagues,” The Pittsburgh Press, August 3, 1939.