In December 2005, a holiday card arrived at the riverside office of Pittsburgh architect Lou Astorino. The message read in part,

“I remember always you when [I] visit the Vatican and admire your wonderful Holy Spirit Chapel. Recently in the conclave all the Cardinals appreciated very much your work and were very happy to have such a nice and inviting place for prayer.”

Signed by former Vatican official Cardinal Castillio Lara, the card referred to an important commission that drew Astorino from the three rivers of Pittsburgh to a small, triangular plot of ground within the Vatican walls. There he worked with an extraordinary team of artisans to create the Chapel of the Holy Spirit.

Astorino’s client and friend, Pittsburgh entrepreneur John Connelly, provided this opportunity. The benefactor for a hotel being built on the Vatican site, Connelly told Astorino that he requested of the Vatican, “‘I want to choose the architect because I know the best one in the world.’ It’s you. So pack your bags, we’re going over there to show them your credentials.” Astorino set off for Rome, where he advised on revisions to the hotel’s design. That advice and his qualifications led to his selection as the first American architect to design and build in Vatican City, and eventually to his being chosen to design a small chapel intended to serve as the place of prayer and reflection for the Papal Conclave when the College of Cardinals came together to elect a new pope. As Astorino recalled, “Was I supposed to design a hotel or a chapel? Everything led to the chapel.”

Connelly had already chosen the chapel’s name, Holy Spirit. Knowing the name and the location’s challenges, Astorino set out to “understand and study everything…the site, and the surroundings, and what the building’s all about.” The site was a small, triangular patch of ground wedged between the newly constructed Domus Sanctae Marthae hotel and the ancient Leonine Wall that surrounds Vatican City. This site might have left others daunted, but it inspired Astorino. He embraced its triangular shape, recognizing it as a symbol of the trinity, and incorporated the triangle into almost every aspect of his design. The result is a chapel that, according to Astorino, “literally and figuratively grows from the Holy Spirit.”

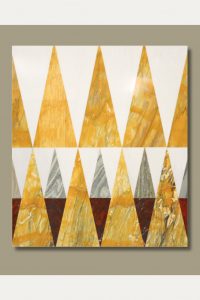

The triangle is all-pervasive in the chapel, from the base of the altar to the pitch of the roof, in the stained glass windows and the capitals of columns. The two most striking uses are found in the luminous ceiling and elaborate marble floor. The pattern of the floor radiates outward from the entrance and uses bands of four different colors of Italian marble, chosen by Astorino with Priscilla Medici at her family’s marble yard. The effect is so striking that the chapel is designed without pews or permanent seating, which would hide the intricate, fractal-like paving.

The ceiling is equally stunning and draws on both natural light and a recessed lighting system. The repetition of the triangle in the bright ceiling and the polished floor reads as a linking of heaven and earth, creating a holy, spiritual ambiance. Astorino’s team included Italian craftsmen, some whose families have worked for generations at the Vatican. Together they created a modern space using traditional materials, a space that reflects the past, but is conscious of the present and the future.

The past literally enters into the chapel in one of the walls. The Leonine Wall, built in the ninth century, and running the length of the site, proposed a challenge. Attaching the chapel to the wall might compromise the strength of the ancient structure or the integrity of chapel, but building a second wall abutting or covering the ancient one felt inappropriate. Instead Astorino designed a glass curtain-wall that looks out onto the ancient wall and allows natural light to enter the chapel. The Stations of the Cross are mounted on the Leonine Wall, and visitors can leave flowers or offerings in the wall’s natural niches.

A final task was to choose artwork from the Vatican’s vast collection to complete the chapel. The most remarkable of these pieces is the crucifix that adorns the apse behind the altar. Chosen both for the beauty of the Christ figure and the impressive size of the cross, the crucifix is discretely lit from the back by a window of the same size. The effect is of a holy light emanating from the crucifix. Other important artwork in the chapel includes the Stations of the Cross by famed Italian artist Enrico Manfrini and an inverted crucifix honoring St. Peter. Placed on axis with St. Peter’s tomb, which sits just a few feet away in St. Peter’s Basilica, it is a poignant reminder of the first vicar of the church.

In addition to the professional opportunity it afforded, this project has held great personal meaning for Lou Astorino, an Italian American and a Catholic. But when asked about his legacy, it is not this special building, or any other his firm has designed or built that he wants to be remembered for. Rather, this man who as a young boy dreamed of designing buildings, says simply, “I want to be remembered for doing good work, creating spaces that have meaning.”

About the Author

Anne Madarasz is chief historian and director of the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum.