Seventy years ago, at the height of our nation’s Cold War frenzy, an American military plane crashed into an icy Pittsburgh river, sparking one of our city’s most interesting – and enduring – unsolved mysteries.

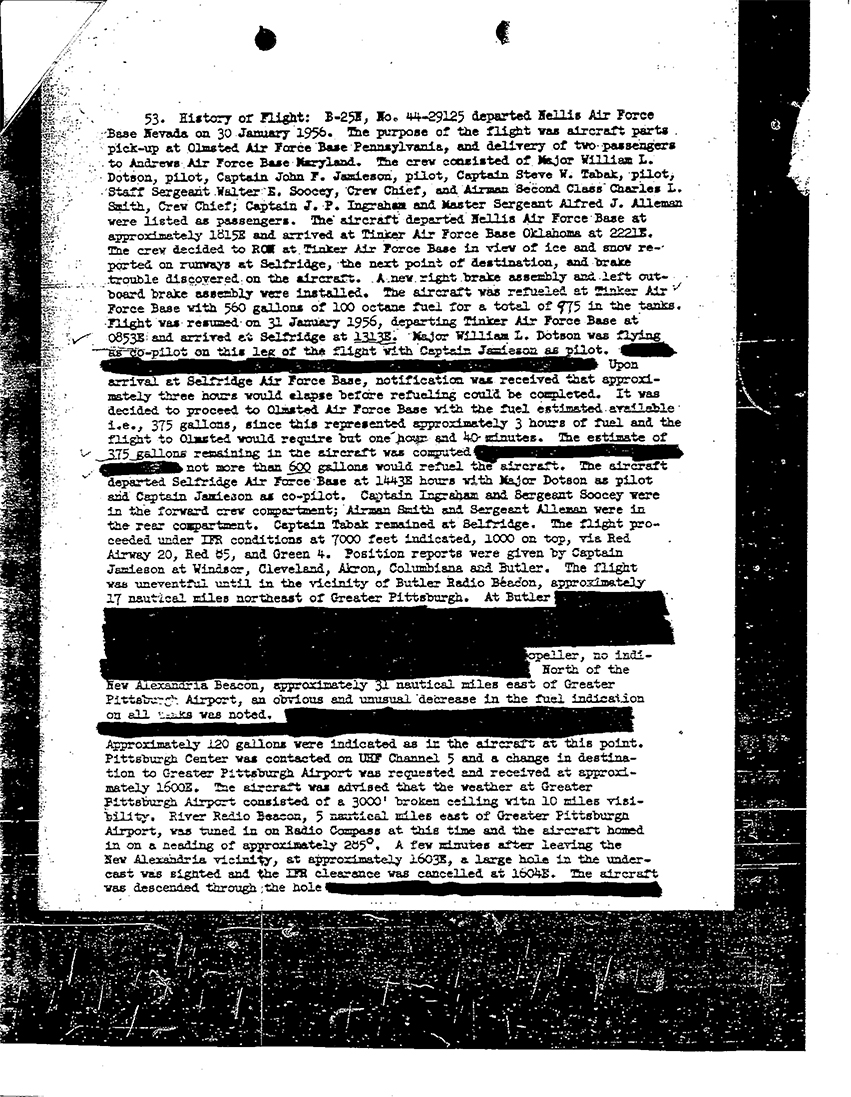

On Jan. 31, 1956, Maj. William Dotson and five crew and passengers were flying over Pittsburgh on a routine training flight from Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada to pick up a cargo of airplane parts at Olmstead Air Force Base in Harrisburg, Pa. During the cross-country flight, the plane refueled at Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma.

At around 4 p.m. on Jan. 31, the crew reported a loss of fuel and requested permission to land at Greater Pittsburgh Airport. When Maj. Dotson realized their fuel wouldn’t last, he instead asked to land at Allegheny County Airport.

At 4:11 p.m., with his fuel supply completely empty, his engine malfunctioning, and without any available airstrips nearby, Dotson was forced to make a hasty decision.

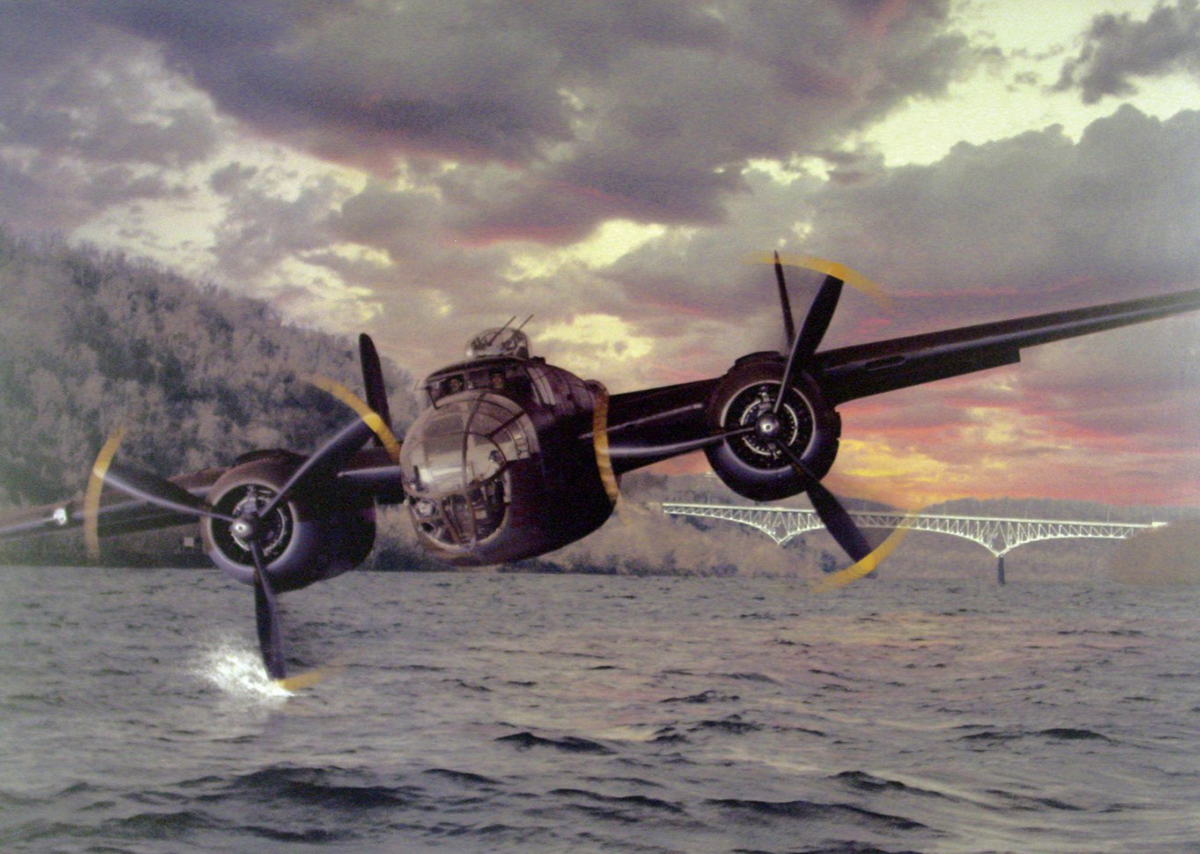

As his B-25 Mitchell bomber glided silently over the Homestead High Level Bridge (today’s Homestead Grays Bridge), Dotson made a wheels-up splash landing into the Monongahela River near the Glenwood Bridge in Hays.

All six crew members survived the crash, although only four were rescued from the 34-degree water. After floating with the plane for 11 minutes, the airmen found themselves in the icy water. Two men, Capt. Jean Ingraham and Staff Sgt. Walter Soocey, drowned while attempting to swim to shore, their bodies not found until months later.

In the ensuing hours, a Coast Guard cutter – the Forsythia – snagged a wing of the submerged plane while dragging its anchor. But the line slipped and the B-25 slid to its watery grave, never to be seen again.

The search efforts by the U.S. Coast Guard and the Army Corps of Engineers continued for 14 days but the bomber was never recovered.

How does a 15-foot high B-25 medium bomber go missing in a 20-foot deep river? Several once-classified documents have helped to shed light on the B-25’s mysterious flight, but its final resting place is still unknown.

Conspiracy theories abound. Some suggest the bomber carried dangerous or mysterious cargo and that the U.S. military secretly recovered the plane’s wreckage immediately after the crash landing to hide its true contents.

Some believe the mystery bomber may have been carrying a nuclear weapon or even a UFO from Area 51 near Las Vegas.

Many believe the highly polluted Mon River corroded the aluminum exterior of the aircraft decades ago, only the steel engines and landing gear remaining.

Others cling to cover-up myths that range from the plane carrying Soviet agents to Las Vegas show girls destined to entertain senators in Washington, D.C.

In more recent years, a team of volunteers known as the B-25 Recovery Group worked with the Heinz History Center with the hopes of locating the lost plane.

Despite extensive research, sonar scanners, and remote-controlled cameras, the Recovery Group found no evidence of the plane during several attempts.

To this day, the “Ghost Bomber” remains one of Pittsburgh’s most famous unsolved mysteries.

The History Center’s B-25 “Ghost Bomber” collection includes newspaper clippings, documents, photos and film related to the crash and subsequent search efforts, and the official accident report, eyewitness accounts, and video of the Recovery Group’s efforts.

For more information, contact the Detre Library & Archives at the Heinz History Center.

To see more pages from the report, please refer to this PDF.