October 12, the day Christopher Columbus landed his ships on the island of San Salvador in 1492, is upon us yet again. Here in Pittsburgh, the Columbus monument in Schenley Park has sat wrapped in plastic for three years. That statue, sculpted by artist Frank Vittor and installed in 1958, was commissioned by the Sons of Columbus, an Italian American organization based in East Liberty, as a gift to the city of Pittsburgh. In the summer of 2020, the City of Pittsburgh led public hearings about whether to remove the monument after a petition for removal had circulated. After collecting comments and votes,1 the Arts Commission made a unanimous decision on Sept. 23, 2020, later endorsed by Mayor Bill Peduto, to remove the statue from public view. Commissioner Andrew Moss stated, “Removal should not be seen as erasure of history; removal of a monument reflects a change in our society and of our public identity as a community.”2

In response to the decision, the Italian Sons and Daughters of America (ISDA), another Italian American organization headquartered in downtown Pittsburgh, sued the city, placing the statue’s removal on hold. A year ago, in October 2022, Common Pleas Judge John T. McVay Jr. ruled that there was no law precluding the city’s mayor or Arts Commission from making decisions about city-owned monuments on city-owned land. He cited Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito’s ruling on a case that involved cities rights to regulate monuments on municipal properties, noting that they represent government speech.3 The case is currently in appeals, with the ISDA’s lawyer George Bochetto pointing to the Pittsburgh Home Rule Charter, a law that requires the additional approval of Pittsburgh’s City Council to bolster the mayor’s decision for removal.4 Oral arguments resumed on October 11, 2023, one day after Pittsburgh’s City Council voted 6-3 to recognize the second Monday in October as Indigenous Peoples’ Day.5

Columbus monument wrapped after decision for removal, 2020. Courtesy of Fabrizio Gerbino.

Since the tragic death of George Floyd in 2020, the American public has engaged in contentious arguments around many subjects, including monuments and memorials, leading to protests, media scrutiny, and actions (both legal and illegal) for removal. No matter what side of the Columbus debate you find yourself on, the current state of the monument in Pittsburgh is disappointing. For those who support keeping the artwork on view, the cloaked figure obscures a symbol they associate with their heritage and allegiance to the United States. For those in favor of removing the statue, the plastic wrap is simply not enough of a gesture, especially after the city announced their decision. As a public historian working in the field of Italian American Studies, I have listened to people’s thoughts about this debate and considered their concerns. I’ve had conversations with individuals with differing backgrounds, ages, social classes, and opinions. Here are a few things I’ve come to realize after three years of discussion, research, and hindsight:

- There is no consensus among Americans of Italian descent – some strongly support Columbus and the desire to celebrate Columbus Day. It is deeply tied to their Italian American identity, and they are vocal about their devotion. Others do not feel a connection to Columbus and reject him as a symbol of their Italian heritage. Some of these individuals openly protest Columbus Day. Then there is a third category that has no opinion; they are not engaged in the conversation and do not care to be. Within these three categories are Italian Americans of different gender identities, generations (both in relation to age and to the Italian immigrant in their family), and social classes.

- No matter the political ideology or position in the Columbus debate, Italian Americans in the first two categories agree that education is the answer to solving the problem. On both ends of the spectrum (and I hope in between) people believe Columbus’s landing in the Caribbean is a significant moment in world history that must be taught; it was the catalyst that began the Columbian Exchange, the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, and the beginning of the near eradication of indigenous peoples in the Americas. These complicated, intersecting histories changed the course of world history and shaped our modern society.

- Depending on where you are in the world, you may learn different historical facts about Columbus. In Latin America, Columbus is depicted as a Spanish figure, while here in the United States we are taught that he is Italian. In Italy, it is widely known Columbus was from the Republic of Genoa and was one of several explorers hailing from the peninsula. In Latin America and Italy, Columbus is revered for his Catholic faith, a biographical fact that wasn’t emphasized in the United States until the establishment of Discoverer’s Day in 1892. These different interpretations of Columbus are tied to the ways that each country used him as a symbol in their nation building.

Grounded in these realizations, the Italian American Program dedicated time to understanding more about these histories, documenting the debates in our community, and disseminating information to engage the public in thoughtful and respectful dialogue. I am not an expert on the Age of Exploration and the subsequent four voyages of Columbus, but I became versed in the 500-year evolution of Columbus from a 15th century figure to an American symbol of patriotism utilized by various communities in the United States (read my previous blog “How Do You Solve a Problem Like Columbus?”).

Promotional image for the film “Columbus on Trial” depicts 15th century explorer Christopher Columbus and 18th century American socialite Elizabeth Willing Powel arguing with pointed fingers. Courtesy of Bongiorno Productions.

In any field of study, it’s essential to create space for questions and differences of opinion to promote learning. Keeping that in mind, we hosted a free virtual screening in October 2020 of “Columbus on Trial,” a short film that imagines the ghost of Christopher Columbus in the 21st century being prepped for trial by the ghost of Elizabeth Willing Powel, an abolitionist and confidante of George Washington. Filmmakers Marylou and Jerome Bongiorno used primary sources such as the letters and journals of Columbus, Bartolomé de las Casas, Queen Isabelle, and other contemporaries of Columbus to create a script that presented a balanced and factual account that addresses his voyages’ connection to the Age of Exploration, colonialism, the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, and the impact on indigenous communities in the Caribbean (Learn more about the film here). One audience member commented in the post-event survey: “I am 70+ years old and throughout my secondary and university educations was never exposed to this level of detail regarding Columbus or his actions.”

After receiving audience feedback, we felt confident “Columbus on Trial” was a resource we could share with educators for in-classroom use and developed supplemental materials. We worked with a member of the History Center’s docent corps, a retired Pittsburgh Public School teacher, to curate resources for students and teachers such as scalable lesson plans and primary sources from the Smithsonian Institution and the History Center’s collections. Materials were designed for distribution in fifth through twelfth grade classrooms and organized as a digital collection on the Smithsonian Learning Lab, a free, interactive platform for discovering millions of authentic digital resources.

In August 2021, we presented an Act 48 workshop and screened the film for a group of 16 educators. A workshop attendee noted, “Middle schoolers are very much influenced by social media, which of course portrays Columbus as a horrible human being. This video showed Columbus as a person and his reasons for his actions. Not excusing, just trying to understand.” Echoing what we heard the prior year at the 2020 virtual film screening, the inclusion of various historical perspectives gave teachers multiple lens to explore not only Columbus’s landing in 1492, but the early years of our nation when slavery was legal (1792), the World Columbian Exposition (1893), and the rise of Indigenous Peoples’ Day movements (1992 to present day).

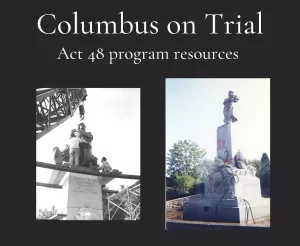

Title slide from the “Columbus on Trial” Act 48 workshop. The image on the left shows the installation of the monument in 1958, while the image on the right shows the same monument defaced in the 1990s. Photographs from the Joseph D’Andrea Papers and Photographs, MSS 1113, Detre Library & Archives.

As we worked to develop educational materials for teachers, the Italian American Program also supported (and continues to support) a research project focused on Pittsburgh’s Columbus monument conducted by students from the University of Pittsburgh’s Italian Program under the guidance of Dr. Lina Insana, Associate Professor of Italian. Titled “Columbus, interrupted: ‘Small’ ethnic philanthropy and the stakes of monumental commemoration,” their study asks the following questions about the initial phases of Columbus monument planning (1909-1926), “Was the Columbus commemoration a significant (and clearly stated) goal of the Italian immigrant community in Pittsburgh? What kinds of Columbus-related fundraising were being conducted in Pittsburgh at this time, and to what ends? What was the relationship between Columbus Day celebrations and the eventual coalescing of efforts to pay for, commission, and dedicate the Columbus memorial at the entrance to Schenley Park? Who were the figures most closely associated with these initiatives, and could they be called prominenti [prominent]?”6

This research project began during the COVID-19 pandemic. Students first worked from home, utilizing digitized collections of historic newspapers from the Pittsburgh region including the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, The Pittsburgh Press, The Pittsburgh Catholic, La Trinacria, and The Pitt News. As students returned to in-person work in 2022, they conducted research at the History Center’s Detre Library & Archives and the University of Pittsburgh’s Hillman Library and Archives & Special Collections, examining primary sources such as L’Unione, the Italian-language (and later bilingual) newspaper published by the Italian Sons and Daughters of America, and the Sons of Columbus organizational records. One of the reasons students are combing through a wide variety of resources is because there is no singular archive that documents the complete timeline of the creation of Pittsburgh’s Columbus monument, which began with community conversations in 1909 and ended with the statue’s installation in 1958.

Pitt Professor Dr. Lina Insana and her students present their research project “Columbus, Interrupted” to History Center staff and members of the Italian American Advisory Council via Zoom, 2021.

While Dr. Insana’s students continue to pursue their inquiry into the nearly 50-year history of philanthropic actions leading to the creation of the monument, they’ve discovered several interesting facts that challenge what we believed about how it came to be:

- The earliest discussions about Columbus commemorations in Pittsburgh were spearheaded by leaders in the Catholic community, an actuality that correlates with other American cities and efforts to publicly venerate Columbus through civic celebrations, parades, and monuments. In this era, leadership within the American Catholic Church and Catholic organizations was primarily individuals of Irish descent, with the Knights of Columbus leading many of these discussions.

- Once Italian immigrants and Italian Americans entered the conversation, they were not unified under a common goal. Some members of the community supported the idea of a memorial (either to Columbus or other notable historic figure), while others maintained that building a facility to serve and represent the community, such as a hospital, orphanage, or school, would be a better objective to work towards. These differences of opinion sometimes led to disagreements; in 1912, we see two separately organized Columbus Day parades happening on the same day, one organized by Catholic organizations in downtown Pittsburgh and the other, organized by Italian beneficial and fraternal societies, in East Liberty.

- Individuals leading these conversations about Columbus veneration in the early 20th century are who we consider prominenti, a term referring to prominent people who held power, resources, and status, both within and outside of the Italian American community. They were newspaper owners, businessmen, lawyers, and judges, and maintained relationships with White Anglo-Saxon Protestant Pittsburghers who also held positions of power in local government and business.

- The first formal proposal for the Columbus monument was made to Pittsburgh’s Arts Commission in 1926. It was rejected on the grounds that city planners did not like the selected location in Oakland’s Schenley Plaza, feeling that the statue would obstruct sightlines in the neighborhood. News of the proposal was reported in the media, and one notorious American organization protested the project – the Ku Klux Klan.

What the students have uncovered thus far mirrors patterns we’ve seen in Italian American history. Italian migrants came to the United States from different regions, provinces, and villages; their identities were tied to these locations that, until Italian Unification in the mid-19th century, were not connected under one nation-state. We call their worldview campanilisimo, which refers to an affinity or belonging to one’s hometown. In Pittsburgh, Italian immigrants came from nearly all 20 regions of Italy; they belonged to different social classes, had varying levels of education, and brought with them unique customs, dialects, foodways, and histories. It’s not without reason that they would also share differing ideas about how they wished to be represented in American spaces.

Untitled (Colombo #3) by Fabrizio Gerbino, 2021. HHC Collections, 2023.130.

The final way that the Italian American Program has engaged with this deliberation is to document the current Columbus debate in the museum’s permanent collection. This is an important function of the museum – when we are no longer here to explain what happened during our lifetime, people in the future will look towards the material culture that’s been left behind to understand the past. The History Center already holds numerous collections related to the Columbus monument and Columbus Day parades produced by the Italian American community. We also have collections that document the previous vandalism of the statue, and the Italian American community’s efforts to repair the damage. Most recently, we acquired a painting of the statue in its wrapped state. Titled “Untitled (Colombo #3),” this oil painting on watercolor paper is one of several studies made in 2021 by Italian-born, Italian-trained painter Fabrizio Gerbino of Stowe Township.

Gerbino visited the monument in 2020 within days of the city’s decision to remove it from public view and found that the bronze statue and granite base were wrapped in a plastic covering. He photographed the encased figure from several angles, and these images became the basis of his paintings. His compositions are a study of materials (metal, stone, plastic, and tape) and their aesthetic qualities, not a commentary on Columbus or the American debates surrounding his legacy. Gerbino commented that, “You should leave a little bit of the door open for people to interpret your work.”7 His apolitical stance and focus on the wrapped monument’s materiality makes his rendering apt for broad interpretation, allowing space for multiple viewpoints and opinions.

In a country where one of our nation’s founding documents, the Bill of Rights, grants us freedom of speech, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, and freedom to petition, we will have no shortage of disagreements, especially as it relates to how we as Americans would like to be represented to our fellow citizens and the world. We’ve built a society that allows its inhabitants to exist as individuals in a culture made up of people of differing backgrounds. Access to such freedoms task us with the great responsibility of balancing our conflicting ideas. Pittsburgh’s wrapped Columbus monument challenges us to uncover the past, dig into our shared histories, explore the meanings behind the commemoration, and reckon with its impact in this contemporary moment. It’s an opportunity for us as citizens to work together to find common ground and ways to resolve differences through civil discourse.

1 The Arts Commission received 5,272 responses to their survey: 1,937 for removal, 1,818 for no action taken, 1,445 for replacement, 65 for alteration, and 7 didn’t indicate an action.

2 Atiya Irvin-Mitchell, “Peduto recommends Columbus statue removal after Art Commission Vote,” Public Source, Oct. 9, 2020

3 Ward, Paula Reed, “Judge: Pittsburgh officials have right to remove Christopher Columbus statue in Schenley Park,” Trib Live, Oct. 3, 2022

4 ISDA Staff, “ISDA Appeals Judge’s Decision Concerning Removal of Pittsburgh’s Schenley Park Columbus Statue,” Italian Sons and Daughters of America, Oct. 5, 2022

5 Felton, Julia, “Pittsburgh to celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day starting next year,” The Tribune-Review, Oct. 10, 2023

6 Insana, Lina, “Undergraduate Research Group ‘Interrupts’ Columbus,” European Studies Center Newsletter, Summer 2021

7 Wiggan, Jamie, “Artist says treating Columbus painting as political statement would undermine art,” Hyperlocal Media – Gazette 2.0, October 14, 2021

About the Author

Melissa E. Marinaro is the director of the Heinz History Center’s Italian American Program, and also the author of Highlights from the Italian American Collection: Western Pennsylvania Stories.