Though a Canadian scene, such encampments of American Indians were common on the Ohio River and its tributaries in the 18th century.

Research for Pittsburgh, Virginia—the Fort Pitt Museum’s new exhibition that explores the roots of the 18th-century boundary dispute between Pennsylvania and Virginia and the 1774 conflict known as Lord Dunmore’s War—involved a deep dive into the community of Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania on the eve of the American Revolution.

everyday Scots, but this portrait of a young woman of African descent may be unique.

By the early 1750s, Virginians based in Williamsburg regarded what is now Western Pennsylvania as an extension of their own territory, a feeling that intensified when the land became legally available to British subjects following the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768. The following year, the Penn family, anxious to solidify their own claims, had the very medieval-sounding “Manor of Pittsburgh” surveyed and opened a land office in town. Following the British evacuation of Fort Pitt in 1772, which effectively removed the last restraining influence on both colonies, the rush was on. Pennsylvania incorporated the territory into their new county of Westmoreland (1773) and Virginia annexed it as part of their westernmost county, Augusta, the following year. The colonial tug of war over ownership of the region, which rejected local American Indian claims entirely, meant that the area around Fort Pitt became a melting pot for two colonial cultures and several immigrant groups (primarily German and Scotch Irish), as well as a frequent destination of American Indians from the eastern Great Lakes and Ohio Country.

During the course of our research, the lives of Pittsburgh’s Delaware, Shawnee, Mingo, and Euro-American residents came into sharper focus, illuminating a “neighborhood” with a vibrant, and ever-changing, cast of characters motivated by a variety of economic, social, and political factors.

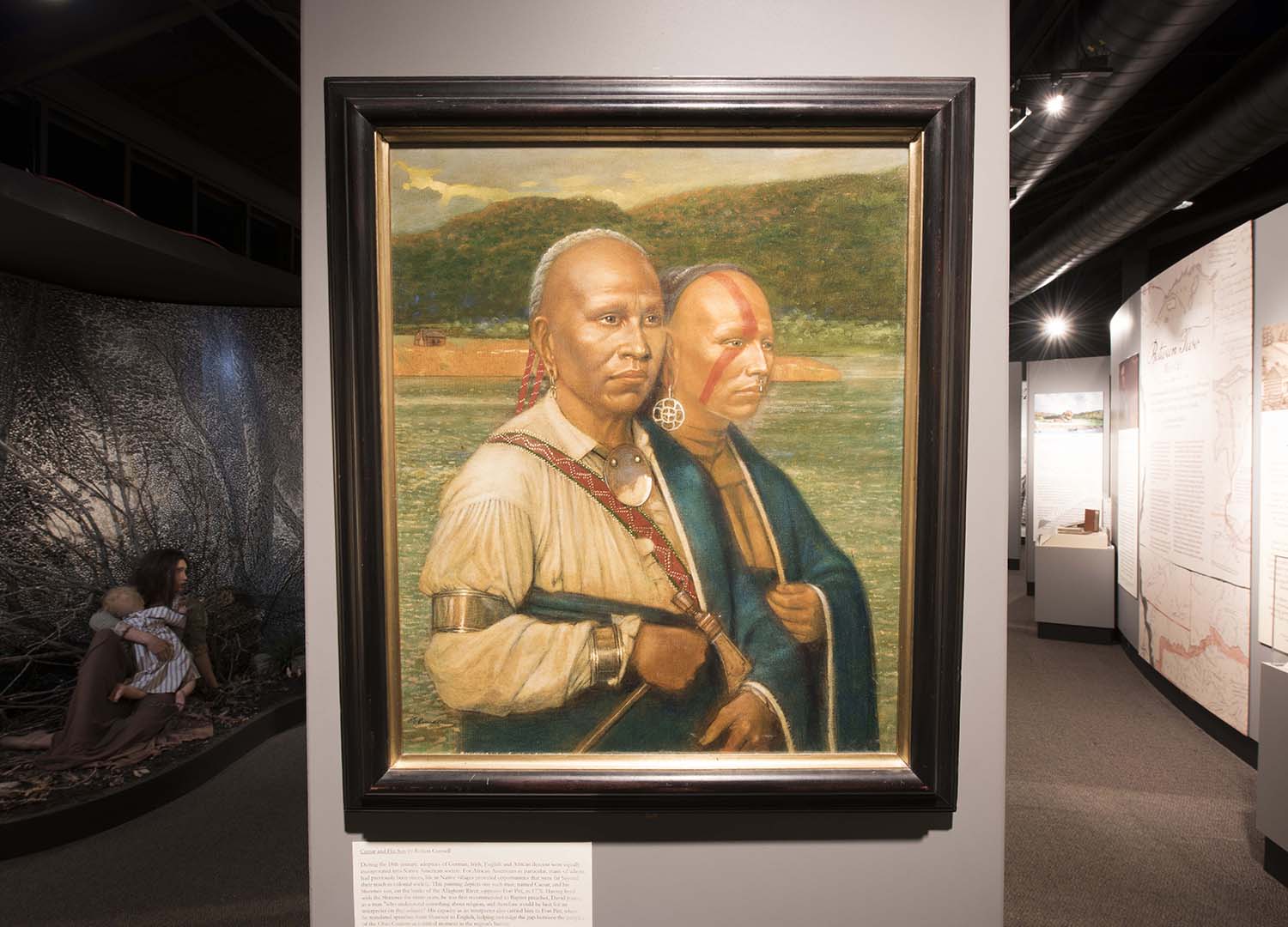

Despite this insight into one of the frontier’s most diverse communities, Pittsburgh’s early African American population, both free and enslaved, remained somewhat elusive. Often left out of official accounts, even in the period, their experience was critical to our understanding of the cultural tapestry that was early Pittsburgh.

Far from simply being present, Ohio Country residents of African descent played a key part in some of the prominent moments in our early history. In the fall of 1757, an enslaved man named Francois fled Fort Duquesne, ultimately providing key intelligence on the French fortification to the Executive Council of Virginia. Acknowledging both the importance of his message and the risk he took in delivering it, the Council ordered that he be “manumitted and set free, and that the Clerk give him a Certificate thereof.” The following year, the expedition led by Gen. John Forbes captured Fort Duquesne and gave Pittsburgh its name. In another notable escape, an unnamed man owned by Levi Andrew Levy, a trader at Fort Pitt, effectively stole himself in 1761. According to trader James Kenny, the man had “run Away with ye Indians,” a carefully calculated move that may well have led not only to his freedom, but also to a place in a society where his status was not necessarily linked to the color of his skin.

The Afro-Shawnee orator Caesar, likely captured and adopted following a frontier raid earlier in the 18th century, is a case in point. Rising to prominence, his presence as a translator and bridge between Shawnee and European cultures was often requested, notably at the Second Treaty of Pittsburgh in 1776. For Caesar, the occasion must have been one of many that contrasted the life he ultimately led with the one he might have. As would have been evident to any visitor to 18th-century Pittsburgh, for most African Americans, the Ohio Country was not a land of opportunity.

As we searched for more evidence of the African American experience in Western Pennsylvania just before, and during, the American Revolution—a time when Virginia claimed much of the same territory, including Pittsburgh—one set of records, housed at a local university, yielded invaluable information on the presence, and impact, of slavery in our region.

Continue on and read part 2 of this series on the African American Experience in Pittsburgh, Virginia.

Mike Burke is the Assistant Director of the Fort Pitt Museum.