1 The Gulf Oil Historical Society offers brand information, including about the first station at http://www.gulfhistory.org/specs/stations/page2.html. The mention of previous Gulf stations refers to others who were selling Gulf gas such as Harvey Dauler’s Petroleum Products Company station.

2 “First Drive-In Filling Station Historical Marker,” dedicated July 11, 2000, at http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=1-A-112. “Gulf Refining was the first company to professionalize the service.”

3 Six years after Model T intro, gasoline replaced kerosene as the country’s leading refined petroleum product. Michael Karl Witzel, The American Gas Station (Osceola, WI: Motorbooks, 1992), p. 29.

4 The 1905 story is recounted (though mentions a hand pump and not gravity) in the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for “Gardner & Tinslev Filling Station” in New Cambria, MO, 2002, at https://mostateparks.com/sites/mostateparks/files/Gardner%20and%20Tinsely%20Filling%20Station.pdf

5 “1st Gas Station Argued: Gulf Kicks at Standard Claim,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 5, 1966, p. 10; “Service Station Controversy,” The Morning Record, Meriden, CT, Sept. 29, 1966.

6 John A. Jakle and Keith A. Sculle, “The Gas Station in America” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1994) p. 131-132.

7 See Reighard’s history at https://martinoilco.com/reighards/.

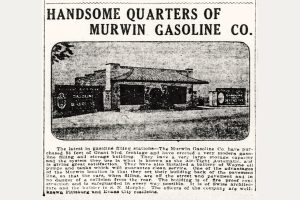

8 “Handsome Quarter of Murwin Gasoline Co.,” Pittsburgh Press, June 29, 1913, p. 17.

9 “Gasoline Supply Co.” ad, Pittsburgh Press, Nov. 16, 1913, Editorial Section, p. 6.

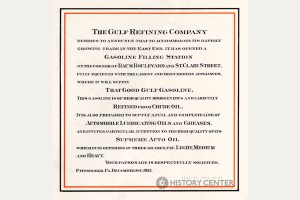

10 The Gulf Oil Historical Society says that Gulf’s “true ‘Birthday’ was November 10th, 1901. On that date, in Pittsburgh PA, the charter for the ‘Gulf Refining Company of Texas’ was signed. This was the first official use of the word ‘Gulf’ as an oil concern,” at http://www.gulfhistory.org/specs/index.htm.

11 Sculle p. 100.

12 Figures are from Motor Vehicle Registrations via www.allcountries.org/uscensus/1027_motor_vehicle_registrations.html, sourced from the U.S. Federal Highway Administration, Highway Statistics, annual:

1900 8,000

1905 79,000

1909 312,000

1913 1,258,000

1915 2,491,000

13 Gabrielle Esperdy, American Autopia: An Intellectual History of the American Roadside at Midcentury (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2019), online at https://www.google.com/books/edition/American_Autopia/QeONDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=pittsburgh+architect+%22James+Giesey%22&pg=PT52&printsec=frontcover

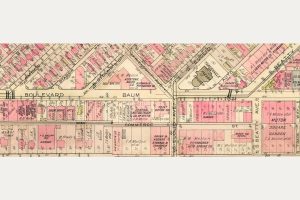

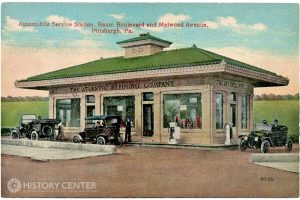

14 Brian Butko, Luna: Pittsburgh’s Original Lost Kennywood (Pittsburgh: Heinz History Center, 2017), p. 45–46. Before it was complete, Baum had been Atlantic, and then briefly, Atherton Avenue.

15 H.S. Moorhead, “Old Baum Boulevard,” The Orange Disc, November-December, 1953, p. 11.

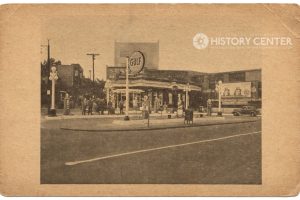

16 As historian Robert Bruce noted, by 1919, “For more than a mile this section of Baum Street, or Baum Boulevard, is the ‘Automobile Row’ of Pittsburgh; and even a run through without stop impresses the stranger with the number and variety of motor car agencies, many occupying their own large and costly buildings,” per Robert Bruce, “The Historic Philadelphia-Pittsburgh Highway—Part XXVII,” Motor Travel, September 1919, p. 35 (p 29-37). This is the magazine of the Automobile Club of America. Society could sense the coming tidal wave: a June 1913 newspaper article lamented that the end was near for the hitching post, the livery stable, and the blacksmith now that the automobile has become so ubiquitous, bringing with it garages, repair shops, and gasoline filling stations. But the article was not negative—it saw far greater opportunity for manufacturers to turn to automobile needs, per “What has Become of the Hitching Post?,” Pittsburgh Post, June 25, 1913, Sporting Section, p. 3. The July 23, 1913, Horseless Age mentions Baum Boulevard businesses U.S. Tire, Buick, Forbes, Ford, Henderson, Locomobile, Oldsmobile, Wahl, Williams-Halsey, Winton, and Pittsburgh-Haynes Automobile Co. The East Liberty market house had been taken over by the Automobile Dealers’ Assn. and renamed Motor Square Garden.

17 Obituary for J.H. Giesey, Pittsburgh Press, November 18, 1938, p. 4, states that he was an architect in Pittsburgh for 20 years, c. 1899¬–1919.

18 “Drop Building 28 Inches in the Hump District,” Pittsburgh Press, June 1, 1912, p. 2. At its largest excavation, the hump was lowered 18 feet.

19 “New Office Building for the United States Aluminum Co.,” Pittsburgh Press, June 14, 1914, p. 36.

20 It is still there as Allen Hall for the University of Pittsburgh, per Patricia Lowery, “Remnants of Pitt’s ‘Campus Beautiful’ May Face Demolition,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 7, 1993, Sunday Magazine p. 12, and “The New Mellon Institute is a Modern Research Laboratory,” Pittsburgh Press, February 14, 1915, p. 8. A 1916 clipping states that he was designing a residential home.

21 Building information is from Moorhead, 1953. H.S. Moorhead was also president of the Pittsburgh Transportation Association, per Gas Saving Accelerator Co. ad, Pittsburgh Sunday Post, June 20, 1920.

22 The builder said anchors had to run down to the footers to keep the roof from blowing off, per Moorhead, p. 11.

23 It’s widely reported that on the exact same day, December 1, 1913, Ford introduced the moving assembly line to mass produce cars, but it’s not true. Experiments with a moving assembly line had been underway for some time, with full use underway on October 7. The December day saw a test of making the line longer, per Horace Lucian Arnold and Fay Leone Faurote, Ford Methods and the Ford Shops (New York: Engineering Magazine Co., 1915), p. 136.

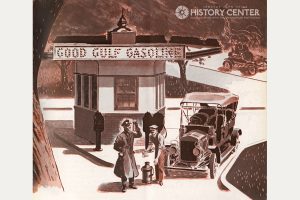

24 F.P. McLaughlin, “We Were First!,” The Orange Disc, March-April, 1940, p. 3.

25 McLaughlin, 1940, p. 4.

26 Ibid.

27 McLaughlin, 1940, p. 5.

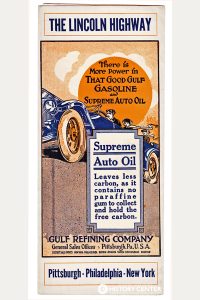

28 Harold Cramer, “The Early Gulf Road Maps of Pennsylvania,” Articles on Historical Maps of Pennsylvania, https://www.mapsofpa.com/article5.htm.

29 Penn was also the Lincoln Highway. Duplicate stations had also opened in Philadelphia and Atlantic City. This station was opposite Columbia Hospital, just west of the PRR tracks, per and “Gulf Refining Co. Locates New Station,” Pittsburgh Sunday Post, October 29, 1916, Sec. 3, p. 7, and “New Gasoline Service Station is Completed,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, October 29, 1916, Sec. 6, p. 4.

30 National United Service Co. of Detroit, as reported in Horseless Age: The Automobile Trade Magazine, May 27, 1914, p. 817.

31 The chain was launched in 1914 per Sculle p. 132, and Witzel, p. 29.

32 See for example, “Gulf Service Stations” ad, Pittsburgh Gazette Times, July 12, 1914, Sec. 2, p. 7.

33 Ad, acquisition of new service station, Pittsburgh Gazette Times, Sec 6, p. 3

34 “Gasoline & Oils” classified lists the PPC retail station at 3501 Grant Boulevard, though that does differ from the 3500 address previously listed, per Pittsburgh Press, September 5, 1915, p. 43.

35 “Realty Sales Were of Minor Nature Today, Pittsburgh Press, Oct. 16, 1913, p 16.

36 “Handsome Building Is Planned,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, Oct 22, 1913, p. 15.

37 Opening ad, Pittsburgh Gazette Times, Aug. 15, 1914, p. 11.

38 Information on Atlantic architecture is from Keith A. Sculle, “Pittsburgh’s Monuments to Motoring: Atlantic’s Fabulous Stations,” Western Pennsylvania History, Fall 2000, p. 122–135, 168.

39 Sculle p. 132.

40 See for example, “Anniversary of First Gas Station,” the Southeast Missourian, Dec. 9, 1963. Oddly, Pittsburgh’s over version in the Press was a short feature in the Sunday Roto, Dec. 1, 1963. Also see Rich Gigler, “Who Did Open The First Gas Station,” Pittsburgh Press, July 10, 1983, Family Magazine, p. 1 & 3.

41 “Father of Local Woman Was Gas Station Pioneer,” St. Joseph Gazette, Dec. 3, 1963, p. 2.

42 “New Gasoline Basis,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, Oct. 4, 1908, Sec. 3, p. 5., is the first mention of a Dauler station. Since “Other Notable Sales,” Pittsburgh Post, Feb. 18, 1910, p. 11, is the first mention of Dauler buying the Polish Hill site on Grant near Finland, the 1908 site is likely the Bloomfield Bridge area site. Also see city directories; for example, 1909 lists Harvey Dauler Petroleum 3600 Grant Boulevard, 1917 lists him as President of Petroleum Products at 3503 Bigelow Blvd., and 1919 as President of Beaver Refining Co

43 “New Gasoline Basis,” 1908.

44 “It is noticeable that the builders are not losing sight of the artistic in having architects design them,” this one by architect Sidney F. Heckert, per “Warehouse to Be Built,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, September 24, 1911, Sec. 2, p. 4, and see “Another New Industry,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, October 22, 1911, Sec. 2, p. 6.

45 “Grant Boulevard Explosion Kills One, Injures Ten,” Pittsburgh Post, July 12, 1910, p.1

46 Michael Sanserino, “Fill ’Er Up!,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Dec. 1, 2013, p. D1 & D4

47 “Neville Chemical Company History” at https://www.nevchem.com/history?rq=Dauler/.

48 “Gasoline Supply Co.” ad, 1913. Also see incorporation notices, May 1911.

49 “Handsome Quarter,” 1913. Also see the company ad, Pittsburgh Press, June 22, 1913, p. 16, and “State Charters Granted,” Pittsburgh Post, April 16, 1913, p. 3, showing that the name was a combination of Murphy and Irwin.

50 The 1940 Pittsburgh City Directory shows for the first time that could be located, a listing for 5801-09 Baum of “Smith Lewis G & Co. filling station.”

51 E-mails with Ellen Smith Davis, Houston, Texas, Nov. 30 and Dec. 1, 2017. She added, “I believe the business may have been originally at 138 Whitfield St. based on some correspondence.”

52 Pittsburgh City Directories, 1916–1953.

53 “Anniversary,” Southeast Missourian, 1963, and similar wire service articles. For more recent writing, see “Fill ’er Up: Convenience on the Road, 1913,” in Fran Capo and Scott Bruce, It Happened in Pennsylvania (Guilford, CT: Twodot, 2005), p. 77–80.

54 See, for example, McLaughlin, 1940, and Moorhead, 1953.